Since 2015, the Sindicato Popular de Vendedores Ambulantes (Popular Union of Street Vendors) has been organizing to defend people who work as street vendors across Spain. Known as manteros, vendors can be spotted around most major Spanish cities, selling everything from purses to soccer jerseys. These vendors have mostly migrated from Senegal without official papers, meaning they are targeted by racist policing practices and are forced to contend with fines, merchandise seizures, and deportation.

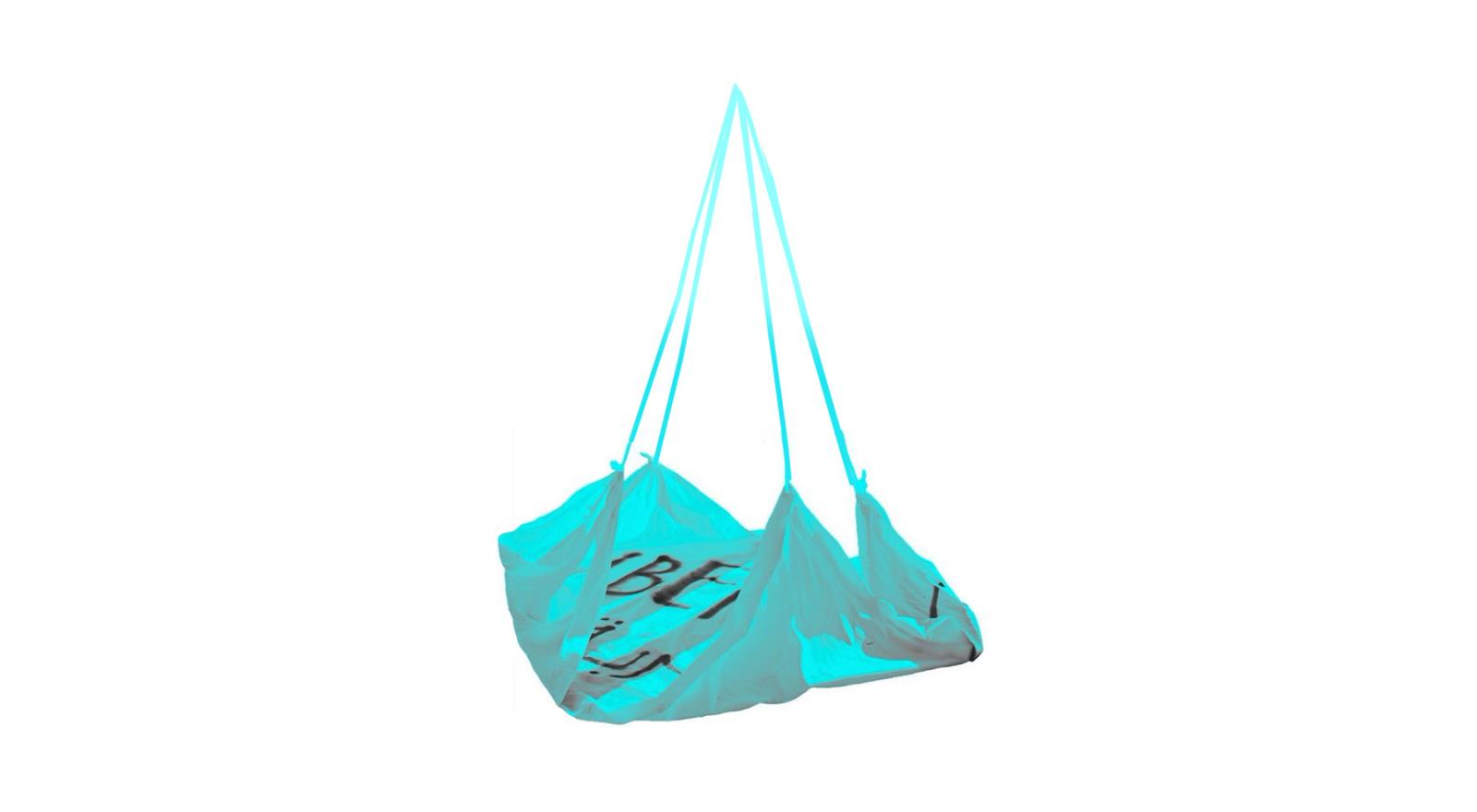

“Mantero” derives from the term manta, or blanket. Typically, manteros will display merchandise on sheets in busy tourist areas. These sheets have a cord attached to each corner; if the police appear, the cord can be quickly pulled, securing all the merchandise and allowing the vendor to leave the area.

The “Sindicato de Manteros” was organized to fight for the decriminalization of their work and for an end to racist immigration laws. The union differs from Spain’s traditional labor unions in that it is not recognized by the state, does not negotiate with a boss, and is not affiliated with other unions in the country. It is made up of a network of organizations in numerous cities around Spain that work both locally and nationally to address police violence and racist immigration laws.

I spoke with Malick Gueye, a former mantero and member of the Sindicato de Manteros in Madrid, about the group’s organizing work.

•

Alexia Garcia.— How would you explain the Sindicato de Manteros?

Malick Gueye.— The Sindicato de Manteros is a way of defending the manteros as workers. It’s an organization composed of manteros, activists, and former manteros with the goal of making visible the fight against borders and institutional racism. We believe that the fight against borders is the same fight against capitalism and colonialism that leads to people migrating in the first place.

We’re a collective that’s composed of people who are otherwise invisible and criminalized in Spanish society. Being a mantero is no one’s dream. We’re forced into the streets because of racist immigration laws like the ley de extranjería, which prohibits people who’ve immigrated from working in the “official” job market.

Who are the manteros?

The majority are young and from Senegal. In Senegalese society, it’s common for people without jobs to sell things in the streets. Maybe you sell things in front of your house. It’s really normalized culturally in Senegal. If you don’t have a job you have to find a way to survive.

And the majority don’t have papers?

There are some people with papers, because even with papers they’re often neglected by or rejected from the labor market because of racism. But yes, the majority don’t have papers. Often people get fined for selling on the street, and those fines will hurt them in their application for papers. In the end, you’re in a hole that you can’t escape. Because if you can’t pay those fines, you’re not going to get papers.

It’s not a job we want. Every mantero, if they had an opportunity for a different job, would leave the manta, fast. It’s a job that generates a lot of stress. It’s work that faces a lot of police harassment and other kinds of aggression from people in the street. People are manteros because they don’t have other opportunities.

What does your organizing look like?

We have meetings regularly, and we take on various campaigns. We host actions, panel discussions on issues like institutional racism, and vigils for manteros who’ve been killed by police. Our goal is to make visible and explain to people why we’re vending in the streets and to shed light on the racist laws that prevent us from getting other jobs and education in Spain.

We also have events, parties with Senegalese food and African music, and create spaces for people to talk with one another and build a support network.

We’re a collective composed of activists, former manteros, and current manteros. It’s really important that we’re not all current manteros, because the manteros who are actively vending in the streets often don’t want to be shown in the press. They don’t want to speak up, because if they speak up, the police might figure out who they are, and that will lead to more harassment. The former manteros can be the public face in order to allow people who are currently more vulnerable to remain anonymous as they organize and sell on the streets.

Can you speak more to your organizing structures?

We have meetings once a week, in the afternoon. Usually, decisions are made collectively in those meetings. We always try to arrive at a consensus. If it’s a more complicated decision we try to talk with our networks to prepare everyone for a conversation and debate the following week. But in the majority of cases we come to a consensus.

There’s no process for people to become members, nor do we keep a formal membership list. Everyone who sells in the streets and activists are welcome in the union.

At this moment we have spokespeople, and if there are other tasks, we organize committees for each of those tasks. For example, we have a communications committee, a committee of spokespeople, a committee organizing the meetings, and a logistics committee. We really only organize in these groups; we don’t use official positions.

How many manteros would you say are in the union?

In Madrid we’re only 80 people. Not all the manteros in Madrid come, you know? The majority come, and if they've been around for more time they come, but not everyone comes to the meetings. The work we do is to make visible the work of all manteros, not only in Madrid but in all of Spain.

There are a number of collectives of manteros in other parts of Spain. What affects us in Madrid impacts people in the same way in Barcelona, in Valencia, in Zaragoza, etc.

How did you start? Was there a specific event that led to the formation of the union?

The union formed out of another organization, Asociación Sin Papeles de Madrid, or ASPM, (Association for People Without Papers in Madrid), which started in the early 2000s. This group had been denouncing the laws that impact the manteros and all people without papers.

In 2011, a huge anti-austerity movement kicked off in Spain following efforts from the Arab Spring to actions in North Africa, Greece, and Portugal. There were huge protests on the 15th of May (15M) in Spain. This took a lot of attention away from our work, because people were less interested in discussing racism and immigration, in light of other themes. We were at a standstill.

Later, in 2014, we elected a new government that was more politically left. A lot of us were thinking that this government would help us, because a lot of our activist friends and comrades were elected. Yet with this government, we started to see more aggression towards the manteros. There were many cases of police attacking manteros, breaking their arms or legs, and in this moment we realized that we needed to do something. We began to form the union in order to try to defend and make visible the situation of the manteros.

Was it difficult organizing the union during the lockdown? How did the quarantine affect your capacity to organize and build community?

What was more difficult was the precarious lives of the manteros. It’s a really vulnerable community. Imagine the stress that you’d have if you weren’t going to make any money in the coming months and you still had to pay rent and utilities. Within Spain during the state of alarm there wasn’t any form of support for people without papers. During that time, our work focused on mechanisms like donation campaigns to build a resistance fund so that we could distribute money and help people survive the pandemic.

We also tried to communicate with people who were experiencing a lot of stress in order to calm them down. The people were in a difficult situation, and they needed to know that there was a collective looking for ways to help them. The meetings were a social space to talk and discuss, for people to say what they were thinking in order to find solutions, to help each other.

I know there were groups of manteros distributing food and supporting folks during the quarantine, and I know you all ran a fundraiser to secure money for folks who couldn't work during the state of alarm. You’re not a traditional workplace union, but rather more of a network of defense, right?

Yes. Also, our comrades in Barcelona run Top Manta, a volunteer organization that sews clothes and now masks to support people and raise money for a general defense fund. In 2015 they started making clothes and fundraising to support people who need lawyers or who are trying to get papers. Their work became even more important during the coronavirus state of alarm and quarantine because the manteros were not able to work.

Did the government pause deportations during the lockdown? Or were people more vulnerable at home and with the lockdown restrictions?

At first they stopped deportations, because there weren’t any flights. But this isn’t only about deportations; Black people suffered more racism and police violence during the lockdown. We saw a lot of videos of the police harassing Black people.

I’ve heard that you all act as a hub for folks who are immigrating — when people arrive in Madrid they can get in contact with you and you’ll help folks get set up here. Do you do community self-defense work more broadly?

It’s less the union that’s doing that work, and more about the forms of solidarity that have always existed among Senegalese people here. The first manteros who arrived in Madrid lived in a hotel in Plaza Nelson Mandela in Lavapiés [a neighborhood in the center of the city]. And when other people from Senegal arrived they were sent there. Everyone lived in this hotel, because no one would rent an apartment to Black people in Spain.

If something bad happened, something racist pertaining to immigration laws, we always had solidarity. Solidarity isn’t about giving scraps; it’s about sharing. We’ve always been clear about this. With the collective we tried to distribute supplies and help people however we could. And we’re often criminalized for this. People say, “How do people arrive and you all help them? Is it because you’re a mafia?” No. Spanish society is really unsupportive, really racist, and there are a lot of things that they don’t understand, including solidarity. They think that if people help, they have a lot. But we’re people who don’t have anything — it’s about defending the community and trying to help each other.

What are some of the main problems you’ve run into while organizing?

There’s a lot of talk about how we’re this network that’s a “mafia.” As if we have a ringleader who owns all the merchandise and is exploiting all the other workers. That’s not true, and we can show you. It’s simply a way to further criminalize our work, or make supporting us a question of morality — “Don’t buy from them because you’re only aiding a mafia.” When you want to criminalize a group, you need moral justifications.

People also don’t want to be associated with our union because they’re already vulnerable. If you speak up in the press, you may fall victim to further police harassment and violence. That’s why it’s important that our collective includes more than just current manteros.

At this moment in Europe, we’re in a racist crisis. You see this in European politics when we talk about refugees and the borders. Every day in our society, we’re normalizing migrant deaths at sea. And this is something supported by racist political parties. Today, if you are racist, you’ll get votes. If you promise to criminalize immigration, you’ll get votes. We see these ideas travel through society. Racist people are further empowered to target migrants in the streets. We see this a lot in Spain.

How do you respond to the extreme right? And specifically to right-wing appeals to economically vulnerable white people?

When we talk about capitalism, we’re talking about how capitalism is racist and classist, right? When capitalists try to blame poor people, they are trying to provoke a war between poor people. White people in precarious situations will often blame immigration. Capitalism always tries to create tension among the lowest classes of people.

We always organize and join with anti-fascist collectives. We always try to work together, because we need them. Racism is a social problem, and in order to fight against a social problem we need a lot of social pressure. To get people to talk about and address these issues that they normally deny, we must work together. For example, we need a lot of social pressure in order to denounce racist aggressions.

It’s difficult to address these narratives. Those of us who are anti-racist work hard to read a lot and verify everything before we make arguments. But the racists, the people on the extreme right, don’t need a single fact-check. The power that maintains racism is this. We’re not talking in terms of human rights — we’re talking about power. And with this type of power, when you have a racist position, your political party gets votes. If you have more money you have more tools to popularize racist ideas. We have to confront them and address their lies, because if not they will control the discussion.

Has anything changed in your organizing or your organization following the most recent struggle in the U.S. against racism there?

Maybe there’s more focus because of what’s happening in the States, but we’ve been here for years, many years, fighting, organizing, and working with immigrant collectives in order to denounce racism and the ley de extranjería. The anti-racist movement here is nothing new. People think that the anti-racist movement is something that’s coming from the United States. No. We arrived here. We saw what was happening here. We saw the racist laws that exist in Europe, and we’ve always denounced it. The cops have always been committing abuses and racist aggressions towards the manteros. And as people without papers, we have never had freedom of movement.

What other campaigns are you currently working on?

We’ve been supporting the campaign Regularización Ya, or “Papers for All,” with a number of other collectives and organizations across Spain. We think that this campaign in Spain is fundamental to addressing the immigration laws, which segregate, discriminate, and neglect people who are migrating. It’s important to give rights to everyone in the world, not just to some while leaving the others behind.