For as long as I can remember, I’ve been the type of person who would rather eat five cookies or none at all. I’d rather give a dessert away than share it, would rather devour than savor. My hormones fluctuate on a reliable monthly cycle, delivering a week of ravenous hunger against a week of complete ambivalence toward food. During the times when I’m eating-crazed, I love food and feel intensely happy because of my love of it. During the times when I’m eating-apathetic, I feel like food has no impact on my life, my interests, or my desires. These are not states I summon. They are states that occur and subside of their own accord.

On all scales, be it day to day or month to month, I notice that my intervals of scant eating are abutted by intervals of heavy eating. This is the rhythm I fall into naturally, and it’s comfortable. For me, it’s right. My weight is stable and within the range clinically allotted for a woman of my height. I’m in impeccable health; I rarely get sick. The only problem with listening to my body is that my body wants to consume in a way that has been deemed unruly, unhealthy. I appear out of control when I eat to satisfy my larger appetite, mentally ill when I eat as little as my minor appetite prefers.

For many American women, healthy eating is negative space, an imperative discerned in the cracks between strictures on how not to consume. There are a great many more wrong ways to eat than there are right. This is reflected in the numerous modern diagnoses for an array of unacceptable patterns: eating disorders, eating disturbances, “dysfunctional” and “disordered” eating. Most of these we know by name: anorexia, bulimia, binge eating, food addiction. Slowly, veganism and vegetarianism are slipping into this category; they can be used as shorthand to indicate what the DSM-V calls “avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.” Combining impressions from anecdotal experiences, Lifetime movie characters, and sensational news stories yields corresponding images to these diagnoses readily enough: Here is the girl who hides jars of vomit in her closet; the fat woman who cries as she eats her third pizza alone; the teenager who weighs herself three times a day, rationing out celery sticks for all three meals.

Yet what images come to mind for healthy eating? A woman laughing with salad? Two slim, tanned, white people at an organic restaurant’s picnic table? A plate bright with a quadrant of greens, a quadrant of white meat, a small nugget of bread next to a modest helping of beans? Quick experiment: What does a “healthy eating” image search yield? Overwhelmingly, it returns pictures of food (produce is popular) or graphics reading simply healthy eating. A “disordered eating” search turns up a plethora of emotive women and provocative bodies, some very slim, some fat, many faceless.

Definitions of healthy eating mostly boil down to the tautology that healthy eating is eating that supports health—albeit with plenty of vague invocations of “right quantities of food” and being sure to consume from “all food groups.” Healthy eating is the shadow of disordered eating and nothing more. It is discussed not as a personally divined way of life but as a structured, learned method of correction. It’s very hard to find information on healthy eating that doesn’t immediately conflate it with weight loss. And it’s is no surprise, then, that instructions for healthy eating regularly employ the same language used to describe signs of illness in some women. For instance, healthy eating should entail goal setting, food replacement, and portion control—behaviors that, according to the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute, are dangerous for a teenage girl if she’s not overweight.

Presumably, the health being supported by healthy eating is mental, emotional, and physical, which only complicates matters since the three rarely respond to any choice unanimously. I may be soothed by a plate of nachos while distressed at the calories, intellectually aware that it’s not “nutritious,” yet physically delighted with the gustatory experience. Or I may be mentally and emotionally at peace with my nachos but end up with digestive unrest. I may even be emotionally, physically, and mentally ambivalent about the nachos, and the meal itself could still be deemed too large, too salty, too fatty to be healthy. None of those configurations is socially sanctioned; each is a sign that the eater in question has conducted himself or herself wrongly and failed to eat healthily. Each could be construed as cause for medical intervention and social censure—or at least social censure in the guise of an intrusive concern.

For the contemporary social narrative around eating, influenced as it is by medical trends and media messaging, who does the eating matters more than what is eaten. If you consume the same foods every day, regardless of how nutritious they’re deemed, you are a candidate for a disordered-eating diagnosis. If you have a strong fear of gaining weight, no matter how perfectly balanced your diet, you are also a possible sufferer. Occasionally, lip service is paid to “listening” to one’s own body when deciding what to eat, but this leaves space for only the most minor fluctuations in appetite. It would not be medically acceptable, for instance, if your body one day decides you should eat 6000 calories and the next day nothing at all. Clinically functional eating is tightly prescribed, no matter how much propaganda is spread about healthy eating being a natural, ideal lifestyle that would suit everybody, if only everybody would adopt it.

For women in particular, the approved methods of consuming food are generally framed by authority figures—nutritionists, women’s-magazine editors, celebrities sharing their tips, “success stories” whose weight loss is worthy of social celebration—as privileges. You can order any entrée at a restaurant as long as you halve your portion. You are “allowed” small treats throughout the day, like raw almonds. Pleasure is minimized, and whatever pleasure is “allowed” is apparently supposed to derive in large part from the triumph of having successfully engineered a healthy eating experience. Small, polite doses of enjoyment are permitted on some special occasions. (One health news site suggests that after researching frozen yogurt purveyors in your area to make sure they’re truly low sugar, you can “order a small serving at the café and enjoy it there.” Delightful!) The assumption in most food consumption advice directed toward women is that they are in the process of trying to lose weight or, at the very least, maintain it, hence the popular “guilt-free” title for so many recipes in women’s magazines. Any woman who pays attention to her food consumption is assumed to be interested first and foremost in body modification.

***

If the urge to to eat heartily of delicious foods is a dysfunctional pleasure, it’s a persistent one, not something learned only by unusually unhappy children hiding in a pantry while parents argue. Overeating spans continents and cultures, and it has a long history, often bound up with cultural rituals. These rituals have been understood by the practicing peoples not as “binging” but as “feasting.” Today, “feasting” and “binging” are some times used interchangeably, but feasting more usually implies a communal mission of overeating for celebration, while binging is undertaken on a personal level for inscrutable, reproachable reasons.

Across cultures, food—and an abundance of it—is a fixture of marking social progress, both small-scale (wedding) and large (harvests). Feasting stands distinct from purging, though the two often go together. This is a matter of practicality: If one truly wants to indulge in a marathon eating session, it may become necessary to clear the contents of the stomach so more can be added. Many times, ritual meals are approached with the understanding that participants will eat past the point of physical comfort. “We shall eat until we vomit” is a phrase attributed to the islanders of Melenesia, who announce it before feasts.

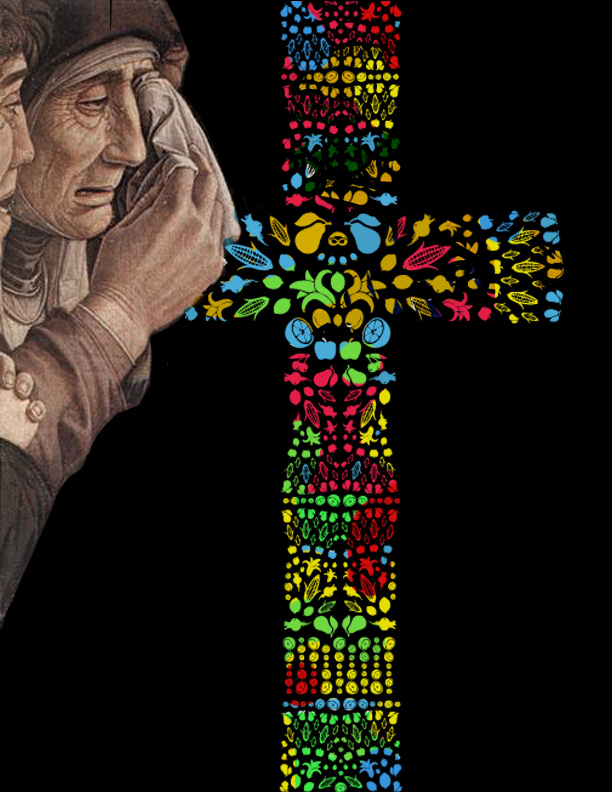

The reasons behind socially sanctioned binge-eating vary, though they almost always relate to celebration, while socially sanctioned vomiting regularly enjoys the legitimizing patina of “purification.” The ancient Greeks, Romans, and Arabs all left behind evidence of regular overindulging and subsequent elimination. The ancient Egyptians subscribed to monthly three-day purges for “health” reasons. Punctuating fasts with feasts is ritualized in many, if not most, religions: Muslims often gain weight during Ramadan because of the feasting that follows their fasts. But fasting is also undertaken without the subsequent overconsumption. Mormons are encouraged to fast on the first Sunday of each month. Present-day Hindus may fast regularly, and the duration spans from a day to a week or even a month. ( Jains even have a concept, Santhara, which is distinct from suicide and describes the holy choice to starve oneself to death. It is still practiced, though there are reports of police intervention.) Websites advocating “detox” diets and companies marketing “cleanses” often approvingly cite the ancient history of purging as proof that periodically starving or emptying one’s body is a healthy thing to do. Similarly, periods of abstention from eating are sometimes framed as letting the digestive system “rest.”

The near universality and the routine frequency of these practices of binging and purging suggest that they are common ways for humans to engage with food. They are not the unpredictably sporadic self-indulgences and self-denials, the diseases that Western culture has recently made of them. In fact, in 2011, a study conducted by doctors in Utah found that Mormons who routinely participated in fast on Sundays were 58 percent less likely to be at risk of coronary disease, results that confirmed two earlier studies. The suggested conclusion was that “abstaining from food on a regular basis leads to metabolic changes that are good for the heart” and further, that these changes could not be attributed to simply having an “overall healthy lifestyle.” In 2012, scientists practically prescribed a lifestyle of regular fasting when they suggested that everyone’s brain health would be improved by severely limiting caloric intake for two days a week and eating freely on the other five. But the same results were not to be expected if someone trimmed their calorie consumption evenly across all seven days, as with stringent dieting plans.

Regardless, most doctors roundly reject fasts and “detoxes” as dangerous and unproven, making exceptions only if they are “religiously motivated.” The eschewing of certain foods and food groups—a.k.a. keeping kosher or eating halal—is also one of the qualifying factors in disordered eating, as is periodic fasting. But religious motivation is a “get out of treatment” free card, further indicating that such behaviors are “wrong” by contemporary Western standards when they are (a) self-directed and (b) motivated by vanity or personal emotional goals—such as exercising self-control—instead of a “larger” social purpose. The patterns of restriction and/or overeating are not pathologized in and of themselves so much as are certain strictly personal motivations for developing them.

This attitude replicates itself with regard to exercise, that other prominent method of body modification. Someone training for an Ironman triathlon may exert themselves for three hours every day and escape medical censure. But someone exercising three hours a day to maintain her appearance for vanity’s sake is sick. Again, overtly social participation rescues a behavior from the realm of illness. That the Ironman participant may be as vain or as emotionally distressed as a freely directed exerciser becomes irrelevant, because the Ironman race, like a Thanksgiving feast, takes place in the presence of many others pursuing the same extreme pleasure. It has finite, communally agreed-upon bounds. Thanksgiving lasts for only one day; an Ironman has three precisely measured components. Conformity bestows the label of healthy. For such intense indulgence to exist outside of socially defined contexts—to be left in the hands of an individual, particularly a woman—is for it be rendered wild and threatening.

***

We all live with the dissonance of a culture that showcases reality TV chefs who wax poetic about the “love” they put into their food, yet prescribes therapy for fat people who are told they misdirect their emotions into what they eat. All of us are susceptible to the constant, conflicting messaging around food: that it tastes delicious, makes us happy, brings us closer to the people we love, and yet is almost solely responsible for most health and weight problems. In such an environment, it seems nearly impossible to develop a pure, “authentic” connection with one’s own consumption urges and instincts. What would my eating look like if I lived alone in the woods? What would yours? I imagine mine would be much as it is now: periods of scant eating punctuated by periods of heavier eating. My ingestive homeostasis would be calibrated to a time frame of several weeks or a month, not a single day or week as many dieting and eating plans require.

When I was a teenager first learning how to make myself vomit, I recognized it as transgressive. The media wanted women to be thin, and most of the people I knew seemed to prefer women to be thin. Yet most of the people I knew, thanks to media scaremongering, also loudly clucked about the tragedy of eating disorders. I’d been given a clear objective while being told the most expedient methods for it were wrong. So I felt slightly exhilarated, even powerful, about approaching the conventional feminine ideal while laying bare authority figures’ useless concern in the process. If the adults around me wanted the world to be safe for teenage girls, they wouldn’t have fed a dominant culture so unapologetically hostile to those girls.

I remember saying as much, if not so concisely, to another 16-year-old friend at a party after we’d both puked, incensed with righteous anger at the injustice of it all. She replied that she was simply terrified of becoming fat and that the possibility haunted her daily. She would go on to become the only girl I’ve known who was hospitalized for her anorexia. Years later, I’d learn that medieval Catholicism condoned female starvation as holy, while the Inquisition later accused self-starving women of witchcraft. Inquisitors even weighed women as a method to determine their guilt. So begins the poem “Anorexic,” by Eavan Boland: “My body is a witch. / I am burning it.”

Of course, the impossibility of a woman satisfying the social demands of her body is not a new theme. Because I have a teenage history of eating disorders, I can’t be trusted to helm my own eating now as an adult. My family decided that my veganism, which I’ve maintained for 12 years, is a cover for continued anorexia. When in Istanbul, after I suggested to my mother that we visit two restaurants in a row, she later pulled aside my boyfriend to ask if I were bulimic. Every year, without fail, my doctor asks me if I’ve purged recently. Regardless of my bloodtest results, my weight, or my response, she recommends I see a therapist who specializes in eating disorders. If a day goes by when I’m simply not that hungry, it’s a sign of a relapse and those around me must rally to tempt me with food. If I’m hungrier than usual, not only is it unbecoming in the usual ways that it’s unbecoming for a woman to eat lustily—I leave crumbs on my face, I drop food on my shirt, I determinedly scrape the last of the pie crust away from the plate with the edge of my fork—but it’s overlaid with the suspicion that I’ll be conscientiously and fiercely counteracting that slip later through excessive exercise or vomiting.

I do still make myself throw up sometimes, when I’ve eaten so much that I feel physically uncomfortable. I would estimate that it happens 10 to 12 times a year, and while I’m not advocating that anyone else adopt this response, I’m not ashamed or embarrassed by it. In the moment, I’ll be disappointed that I overate to the extent that I did, but I won’t lose sleep about it. I don’t return to the table and eat more, or make massive efforts to consume differently the next day. While it’s true that stomach acid doesn’t do any favors to tooth enamel or the tissues of the esophagus, it’s also true that occasional vomiting, whether from the morning-after pill, too much alcohol, or self-induction, is not going to cause serious problems. I consider it as appropriate a reaction as drinking a mimosa in the morning after a night of partying or an athlete’s submitting to a painful ice bath during the height of training.

Though there have been many times I’ve let society influence how I handle and relate to my body, this will not be one of them. I want to live in my own form with pride and joy, wellness and comfort, and peace and, yes, control. There is room for my rare vomiting in that. It is not the final problem to solve; it is not the black mark keeping me from being “healthy.”

The point is not that eating disorders aren’t real. Many people suffer from a seriously damaged relationship to food, and it threatens their happiness, their long-term health, and sometimes their lives. And many of these people are men, whose trouble often goes unnoticed because we are so much more fixated on policing female food intake. It is only right that people in need receive recognition and help. But minutely plotting and achieving a perfect caloric balance every day reminds me more of the darkest period of my anorexia than it does a calm and sustainable lifelong approach to food. To have moderation in all things except immoderation echoes the close-fistedness of my most manic restrictions. I don’t see the health in it. Healthy eating will never be usefully defined as the inverse of disordered eating. It has a life—it is a life—of its own.