Diriye Osman is an artist of glittering style. His paintings and collages feature luminous color and an eclectic mix of images from ancient Egypt to outer space, and his writing is similarly streetwise and mystical, inspired by jazz, hip-hop, the rhythms of prayer, and the syncopated sounds of multilingual urban slang. A British-Somali artist and author based in London, Diriye Osman is the author of the Polari Prize-winning collection, Fairytales for Lost Children, as well as a new novel in stories, The Butterfly Jungle, which narrates the life of Migil Bile, a canny, irreverent, queer British-Somali journalist navigating romantic escapades, the perils of the gig economy, and the loving complexities of his queer family.

Diriye and I talked about The Butterfly Jungle, Afrofuturism, community, and the glory and ghastliness of technological culture.

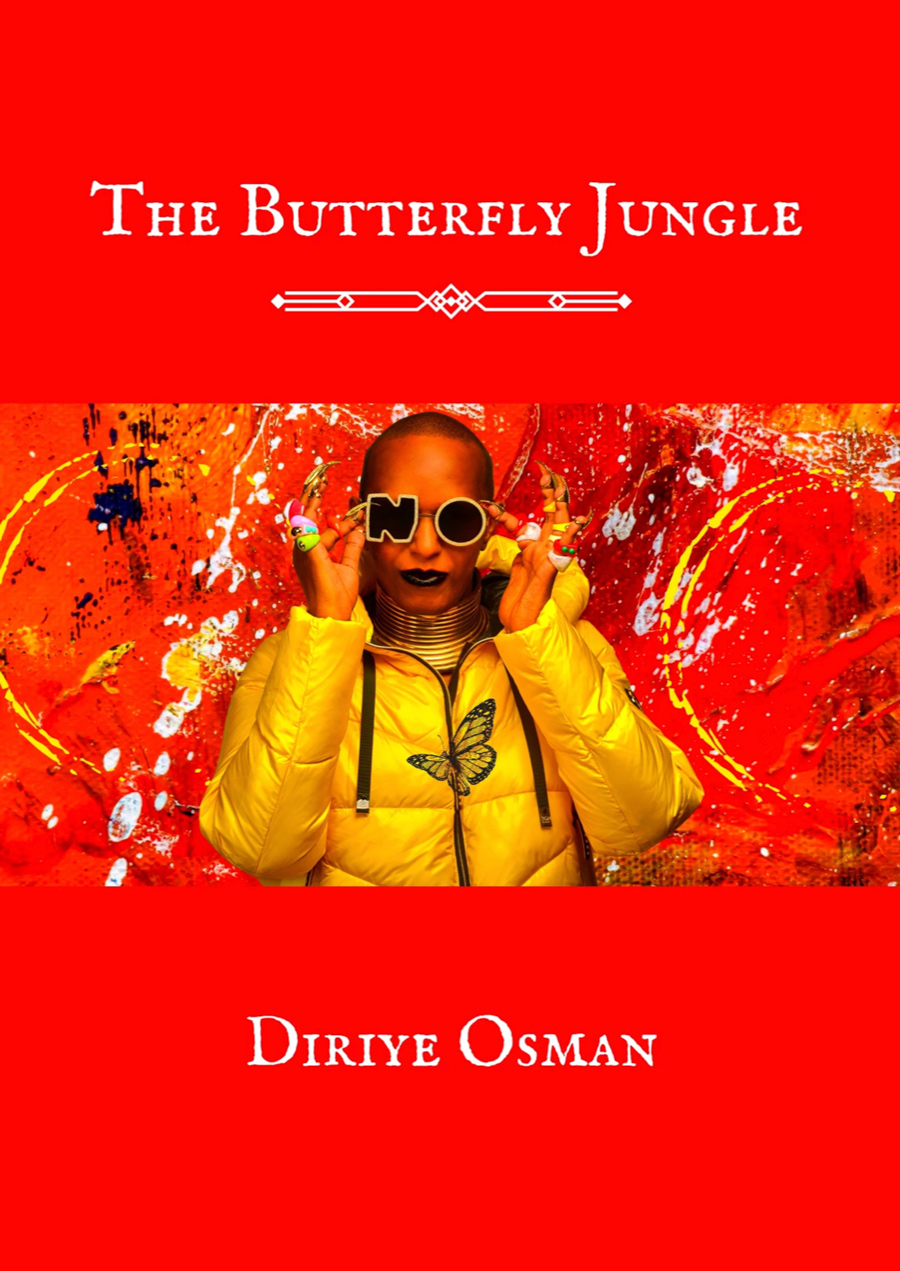

Sofia Samatar: I want to start by asking you about design. The Butterfly Jungle comes to readers as a brilliant burst of color, with a cover decked in photographs and splashes of paint that unwraps to reveal additional photographs of your signature ornate, regal style. Talk to me about these choices, please! What was your vision for the book as an object?

Diriye Osman: I’ll give you the discursive answer, which is invariably more fun. I make all of my work on my phone at this point. It doesn’t matter if it’s writing a book or making a collage or editing videos or articles; everything is made on my phone, and that includes the cover of The Butterfly Jungle. The book was written on my phone and the cover was designed on my phone.

I actually had two different covers initially, but didn’t know what to do with them, so I workshopped them on Twitter. The consensus was that the red cover was litty like a titty on fiyah, and who am I to deny the people? But I also paid attention to the folks who wanted something elegant as opposed to pure bombast. The cover production was the equivalent of a super sexy camel, which sounds like hot nonsense, but it’s true. I was trying to please my day one super fans and new readers alike while also honouring my own idiosyncrasies.

I had complete creative control.

Samatar: The practice of creating work on a phone is fascinating to me—and, I admit, daunting. It’s so small! But of course it is also a powerful computer, and extremely portable. It feels appropriate that Migil, the narrator of The Butterfly Jungle, would leap to life out of this device. He’s an energetic media intersection himself, a digital journalist with tunes pulsing in his ears, his language as global as the World Wide Web, infusing English with Somali, Spanish, Kiswahili, and more. “Beloved reader,” he says, talking straight to us. This is a text with a strong spoken feel (interested readers can hear you read from it here). Is performance important to you? Does it form part of your creative practice?

Osman: I really wanted The Butterfly Jungle to have the energy of a super-fly Somali sheesha session; the flavour, the silliness, the endlessly delicious gossip, the conspiratorial jokes, and of course, the moments when everyone is suitably buzzed enough to drop bombs the size of Benaadir.

With regards to the performance-like energy of the prose, I dare you to name anyone who’s more bombastic than Somalis. We come from a long tradition of performativity and I wanted to reflect that thrilling vigour and vim. We’re so inherently fabulous that, at this point, I’m convinced it’s hereditary. Migil and his motley crew really are the beneficiaries of a bombass, vibrant oratorical history that has seeped into their bloodstream.

Finally, in terms of the usage of phones and the deep immersion into digital culture; I’ve been using my phone as my work station for eight years. I’ve written two books on my phone, I make all of my art on my phone, I write prayers and meditations on my phone, I bank on my phone, etc. At this point, I’m part machine. My phone is how I make my livelihood. But aren’t we all simply extensions of the technology by now? Here in the UK, you need to have a smartphone in order to do anything, whether it is managing your money, paying bills, looking for dates and hookups, shopping for food or furniture, communing with your community, etc.

Technology—and its performative possibilities—is the silk thread that nurtures so many dazzling cultural intersections, and The Butterfly Jungle delights in this.

Samatar: That makes me think of how my father—a Somali scholar of oral poetry—once wrote, “We are people of words. All our poetry! Words, words are us!” Migil exemplifies the rhapsodic swagger that comes from owning language, being made of words and reveling in their texture and sound. He exists in a highly technologized space where orality and literacy blend. Could we call this an Afrofuturist space? I noticed that Migil listens to Sun Ra, and describes his incense as “waft[ing] into the afrosphere,” and it made me wonder about Afrofuturist influences on the book.

Osman: Your father was completely right, may he rest in peace. We are made of words. I’ve been having this conversation with my publisher for a few years now, and the phrase I’ve always used was, ‘We are made of stories.’ I would go even further and say that if you sliced me open, you would find reams and reams of narratives yet to be told. To be Somali is to be attuned to the surrealism of everyday life. We are magical and weird and completely wonderful.

Migil’s world is Afrofuturistic. His small part of South London is predicated on the plurality of queerness and diasporic blackness filtered through the intersection between technology and a slightly hallucinatory, highly specific Afrofabulism. I think of Migil’s love for Alice Coltrane and Sun Ra; I think of how his community is coded in the kind of love that transcends cultural borderlines, but is still distinctly South London.

I know you’ll have noticed this, but there are very few heterosexual characters in The Butterfly Jungle. It’s made up almost entirely of a diverse cast of black and brown queer folx, ranging from a dynamic Trinidadian trans editrix, a Jewish-Somali lesbian therapist, Congolese trans lover boys, gay Mexican cuties, Cameroonian and Israeli neosexuals. This is not to mention Migil’s family who is all-queer; his mother is lesbian, his stepmum is genderqueer, his dad is gay and his stepdad is bisexual.

I really love this intensely wonky setup, which wasn’t designed to be exclusionary. It simply mimics my own reality. Almost everybody in my orbit, from my best friend to my dentist to my local postal worker to my closest collaborators, is on the LGBTQIA+ spectrum.

I wanted to represent this world in all its hyperdimensional triumph and toil.

Samatar: This reminds me of a line in the book that stood out to me: “The queer black body as sacred memory, the mind as cuneiform script, code too complex for modern algorithms.” This phrase strikes me as deeply connected to Afrofuturist philosophy, because it implies inhabiting all of time at once. It reads cuneiform script as code. And it proposes a queer way of being so complex it’s beyond any notion of modernity—a future that can only find expression through ancient concepts of the sacred. It’s gorgeous and so evocative of Migil’s community.

Migil is deeply appreciative of his loving, queer, largely Black community. He tells us, “I was privileged as a gay black bloke in a predominantly white, increasingly racist country because I was insulated from the harsh experiences faced by most folks of colour across the spectrum.” But he can’t live fully in this nurturing space, because he works as a digital journalist, a job that exposes him to online harassment and doxxing. At one point he wonders, “If this technology was supposed to amplify all of our voices, especially those of us who were marginalised minorities, why did I feel that the consequence of poking my head above the parapet was too painful a price?” Can you say more about the critique of technology embedded in Migil’s story?

Osman: I don’t believe social media is a marketplace of ideas, which is how the concept has been upsold to us. I think platforms like TikTok, Twitter, Tinder, etc, are a nexus point for anxiety, body dysmorphic distortions, rejection, fear, addiction and every other chemical imbalance and psychic decay you can imagine.

I’m not a Luddite by any measure (I make my living using this technology after all), but I’m not seduced by how dependent we have all become on these platforms. Do you want to know what psychosis feels like? Psychosis, in its purest form, tastes and feels like a social media pile-on. It’s that simple. The person who is abused on social media experiences the same paralysing fear and trauma as the psychosis survivor. That’s how destabilising these networks can be.

The reason I can navigate these spaces as a queer Muslim man of African descent is because I’ve spent twenty years navigating the mental health industrial complex. Social networks are the new psych wards.

I remember going on a date with a cute bloke a couple of years ago. I had met him on a dating website and he was pretty like money. We hit it off as soon as we met up at the restaurant. As the conversation got cozy and we became suitably relaxed, he said he was going to send me some saucy pictures of himself in booty shorts. I told him I didn’t have a smartphone. This man, who was right in front of me, became irritated that I didn’t have a smartphone. I had seriously harshed his buzz. When I got home, I couldn’t shake the feeling of unease. I realized in that instance that reality was not enough for him. He wanted to kickstart a monogamous relationship—not a sexy romantic liaison—with a hefty dose of abstraction. He wanted to filter me through his screen (even as I was sitting right next to him.)

I remember reading a news item a few years ago that younger administrators entering the workforce in the UK have to literally be taught how to speak on the phone. Most of them don’t know how to have a conversation on the phone because all they know is text-speak. I really believe the technology has not shifted how we see the universe; the technology has subsumed our entire universe.

I try to navigate this reality as responsibly as possible. My Twitter presence, for example, is predicated on sharing good news, beautiful art and photography, videos, meditations, short stories, uplifting playlists. In the same way that this technology can be weaponized as a corrosive device, I’m hopeful it can also be utilised to provide some relief.

At the end of the day, all anyone in this world wants is a sense of connection; we all want to be valued. My job as a writer and visual artist is to offer small nuggets of joy and wisdom that might help others. That’s all.

Samatar: Migil’s online struggles are not the only challenges he faces by any means. He shares his experience of mental illness, sexual assault, and trauma. Yet the atmosphere of the book remains effervescent. Rather than presenting a world without pain, The Butterfly Jungle strives for—as Migil puts it—“lightness as a counterpoint to difficult circumstances.” What was it like to maintain this lightness? How did you find the right balance?

Osman: Sadness is a vital part of life. It’s important to grieve everything and everyone we have lost—and we have all lost a lot here. This is something I sit with every day, but I don’t see this sadness as shameful. It has its own therapeutic implications.

Emptiness, on the other hand, is a flat echo. With sadness, there are nuances to it; different cadences that connect to something primal. Emptiness is akin to throwing yourself down a well without a bottom. Emptiness isn’t even depression. It’s simply emptiness.

Oftentimes, when folks consider fantasia within the context of their everyday lives, prosaic notions come into play; we think of heaven in terms of virgins with tight chochas, we think of freedom in terms of more moula, we think of joy in terms of more sex, more shopping, more capitalistic overreach.

When we take a step back, even the fantasies we create cannot escape the rules of our own social conditioning, which is to say that we are bound by our own humanity—and the range and limits of it.

And yet, we keep loving and we keep hoping and we keep showing up. In the same way that I wouldn’t be here without the medicinal properties of sadness, I wouldn’t be here without jokes and optimism and joy as well. I wouldn’t be here without faith.

I wanted The Butterfly Jungle to present the reader with the unreality of our current moment through a distinctly Afrofuturistic lens whilst offering the literary equivalent of a hug. Love, and all the goodness it brings into our orbit, is the honeyed glow that makes all the struggles of daily living not only survivable, but worthwhile. This book was written from a position of love for every one of us standing at the periphery. That’s why the reader is a confidant in The Butterfly Jungle. It’s my way of saying, you belong here, beloved reader. You can put down your weaponry. This small space is yours, too.