We know that fashion shows are overwhelmingly white. What about virtual fashion shows?

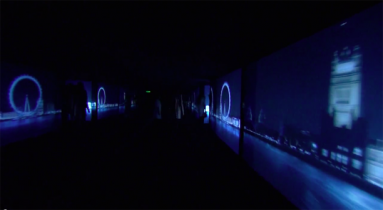

On April 13, 2011, the British fashion house Burberry celebrated the opening of its flagship store in Beijing. Approximately 1000 guests, belonging mostly to Chinese high society and the emergent class of Chinese luxury consumers, filled the 21,500-square-foot sound stage at Beijing Television Centre to experience the “Burberry Prorsum Autumn/Winter 2011 Hologram Runway Show.” As the name implies, the event was both a fashion show and a light show. Floor-to-ceiling video screens displayed immediately recognizable emblems of British culture: Big Ben, the London Eye, and fittingly, British fashion models dressed in Burberry trench coats carrying umbrellas printed with the iconic Burberry check. Demonstrating why the brand is at the forefront of the digital fashion revolution (New York University’s think tank Luxury Lab ranked the company at the top of its Digital IQ Index in 2011 and 2012) the fashion models are computer-generated images based on white British models Cara Delevingne, Edie Campbell, and Sebastian Brice. Flying across a sky of London fog—their umbrellas serving as Mary Poppins-style parachutes—and landing in puddles of London rain, these larger-than-life size white female avatars displayed on the walls and ceiling of the Beijing Television Centre surround and dwarf the mostly Chinese audience.

As spectacular as this exhibition was, it was only a prelude to the main attraction: a runway show of both real and holographic-like fashion models. “Holographic-like” because, despite numerous claims made by the trade and mainstream media, Burberry’s CG models are not true holograms but rather 2-D images captured from one (not multiple) angles and then digitally manipulated with 3-D effects. Still, the 3-D effect is so credible that distinguishing the flesh-and-blood models from their virtual counterparts is nearly impossible—until the virtual models identify themselves, either by multiplying into an image trail or evaporating in a cloud of glitter.

Burberry’s hologram show is telling of the contemporary moment in fashion when Asia, and particularly China, are becoming key luxury markets. For the past few years, one of the biggest financial-news stories has been China’s economic boom and the rise of Chinese luxury consumers. In 2011, the international accountancy firm Ernst & Young reported that China had become the world’s biggest IPO market. This was due in large part to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, which raised more than $50 billion. That’s up 162 percent from 2009. Compare that with the far weaker U.K. IPO market ($12 billion), still struggling to recover from an ongoing debt crisis in the euro zone. The U.S. IPO market, at $16.8 billion, isn’t faring much better.

No wonder, then, that luxury fashion companies based in Europe and the U.S.—Prada, Salvatore Ferragamo, Jimmy Choo, Coach, and others—opted to launch their IPOs in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, or that a range of labels across the price-point spectrum—from Gap and Levi’s to Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Hermes—have been opening hundreds of stores across China since 2009. Gap’s plan to close more than 150 Gap stores in the U.S. and triple their stores in China by the end of 2013 is an effective account of these times. If we needed any more proof of the risen prominence of the Chinese fashion consumer, consider that some European and American brands have begun creating exclusive lines, tailor-made for this very market. These collections are “infused,” as the Los Angeles Times recently put it, “with Asian sensibilities in look, feel and size.” For Prada’s first-ever runway show in China, the designer recreated her cotton dresses with radzmire silk and liberally appliqued sequins. Further strengthening China’s hold on luxury goods is its steady expansion of the e-commerce market expect, which economists expect to outpace existing markets in the U.S., Britain, Japan, Germany, and France combined by 2020.

While China remains a poor country with an average annual per capita consumption of $2,500 (the U.S. per capita average, by contrast, is $30,000), China’s fast-growing population of millionaires (1.1 million in 2012, more than double the reported number in 2007) and the Internet-enabled diffusion of Western consumer culture are quickly transforming this communist nation into what the New York Times has called “The Shoppers’ Republic of China.” Today, young Chinese—mostly between 20 and 30—are buying luxury fashion and microblogging about it on Sina Weibo (China’s version of Twitter), where fashion tips are one of the most popular trending topics.

To be sure, Chinese luxury consumers are not all moneyed. Many, like 22 year-old Lu Jing who earns $943 per month at her advertising job, live on instant noodles and public transportation for months in order to save for a $3200 Louis Vuitton handbag. Nonetheless, we are witnessing a remarkable historical shift in China’s status in global fashion. Once “the world’s factory,” as Thuy Linh N. Tu writes in her book The Beautiful Generation, China is now poised to be the world’s mall.

While the ascendancy of the Chinese fashion market and, more broadly, fashion’s economic shift towards Asia provides the backdrop for Burberry’s presence in Beijing, the show treats Chinese consumers as if they are incidental. In an event that would seem a perfect occasion to showcase Asian models (real or otherwise) as reflections of their target consumers, Burberry presents a nearly all-white cast of fashion models. Rather than spotlight Chinese supermodels or at least use them as prototypes for the digital models, white models overwhelmingly outnumber non-white models on this virtual fashion runway—just as they do on real runways. Only two of the fashion avatars were based on non-white models (Jourdan Dunn, a black British model and Shu Pei Qin, the only Chinese or Asian model in the show).

In the Burberry show, the material significance of this moment in fashion history is turned on its head as the relationship between Chinese consumers and Western luxury fashion companies is rearranged back into a techno-racial colonial world order. The establishing shots of Big Ben and the London Eye situate the iconic brand geographically. More crucially, though, they situate the brand within a history and discourse of technology that has served to rationalize racial hierarchies and differences. As Michael Adas has shown so well, technological discourse is deeply connected with racial discourse. In Machines as the Measure of Men, he writes:

Notions of white supremacy and racial superiority, jingoistic slogans for imperialist expansion, and the vision of a dichotomous world divided between the progressive and the backward have all been rooted in the conclusions drawn by 19th-century thinkers that only peoples of European stock had initiated and carried through the scientific and industrial revolutions.

In other words, technological discourses of European “progress” are constituted against representations of tradition-bound racial “others” who are imagined as either stuck in or slow to move out of a primitive past. The non-West is imagined to be outside the technological time of the modern West. In technological discourse, racial difference is articulated as a temporal and spatial distance between the West and the non-West.

The images of Big Ben, the London Eye, and Burberry designs, accessories, and clothing draw a racial and national link between high fashion and high technology. While the event was physically located in Beijing, Burberry’s YouTube footage of awestruck Chinese viewers snapping photos with their DSLRs and their smartphones render Beijing locals as admiring tourists or outsiders to the virtualized world of high fashion and high technology which, as the image of Big Ben reminds, is calibrated to London time and space. In the opening video, even the time and space of a dreary rainy day in London is idealized over and above the warm spring day in Beijing.

While Chinese consumers are becoming key and controlling players in the fashion market, the Burberry event all but erases this historical shift in economic and cultural power and rewrites history using a familiar narrative. Consider how Burberry’s chief creative officer Christopher Bailey describes the event: “It is a huge privilege to be flying the flag for Britain in the magnificent city of Beijing.” Inadvertently, and so perhaps truthfully, Bailey maps a colonialist metaphor onto Burberry’s expansion into China.

If the visual images that begin the fashion show construct a scopic field organized around British technological time and space, then the actual fashion show, with its holographic fashion models outfitted in British fashions, is organized around the fantasy of digital disembodiment.

The allure of digital disembodiment is especially emphasized each time the holographic models are seen dissolving into digital glitter. This is an optical illusion of whiteness. In Shannon Winnubst’s discussion of what she terms “the infinite desire of disembodied whiteness,” she argues that disembodiment represents an ideal state of being in which “the messiness of material vicissitudes” is transcended. In the context of fashion, the racial implications of “messiness” are routinely translated through a chain of signification like dirtiness, ugliness, and foreignness that are linked to nonwhite bodies and spaces in the Third World or nonwhite U.S. ghettos.

There are far too many instances of racialized sartorial messiness to name in full here but Michael Kors’s AfriLuxe collection for his Spring 2012 campaign serves as an exemplary case. In the editorial, white models are neatly dressed in Kors’s latest collection while African bodies are photographed in, to quote the website Fashionista “dirty-looking earth tone caftans and cargo pants and cashmere sweaters with holes in them.” The tattered sweaters and the dirty clothes are sartorial signs for the “messiness of materiality” that racial bodies signify. The ragged clothes mark the Black bodies as fleshy, corporeal; they serve as material evidence of the hardness and realness of nonwhite bodies and experiences. In contrast, and with the help of lighting techniques, the white models in their designer fashions seem to float above the messy scene of the worn-through clothes and worn-out people.

In the Kors editorial as with the virtual fashion runway, physical and social transcendence are privileges of whiteness. Fashion’s aspirational aura encourages consumers to want to be more than their bodies, transcending the limits of their “figure flaws” as well as bank accounts and closet spaces. Burberry’s holographic models draw sartorial and racial aspirations seamlessly together: to be fashionable is to have the capacity of bodily transcendence is to be white. This is why virtual fashion runways are as homogeneous as their real life counterparts. Raced bodies (whether real or virtual) are burdened with the messiness of material embodiment whereas white bodies are allowed the possibility (and possibilities attached to) transcendence.

Since Burberry’s Beijing show, other fashion companies—including mass brands like Diesel and Forever 21—have produced their own hologram shows. Those that have not are employing a wide range of digital communication media technologies and practices, from fashion blogs to Twitter to virtual fitting rooms. Fashion has doubtlessly embraced the digital age, to little surprise. The digital is the ideal medium with which to realize fashion’s utopian promise of self-transformation, a promise exemplified by fashion models themselves. The work of fashion models is to become something other than they are on each runway and in each photo shoot without carrying the burdens or the traces of their past selves. To realize this self-transformation, fashion demands an unmarked and malleable body—a clean slate, eminently inclined to modification. Thus, digital disembodiment is the ultimate realization of fashion’s promise of easy or in the language of fashion “effortless” transformation. But like sartorial effortlessness, digital disembodiment is an illusion that functions by disavowing racial histories and bodies like the cheap labors of racialized women—mostly Asians and Latinas—who have historically provided the material basis upon which the transcendent hope of fashion is built.

Today, it is also the Chinese luxury fashion consumer that undergirds this fantasy. In and through the Burberry show, these material histories and relations are dissolved into those digital, glittering clouds of fashion dust. Once the dust clears, what is left behind is the live Chinese audience whose bodies are not constituted by the clean, scientific precision of binary codes but instead meat and bones, and all the messy textures, smells, and historical baggage they bring with them. If fashion’s global economic foundations are shifting in ways that blur the meanings and power relations between communism and capitalism, East and West, racialized labor and elite consumption—and I think they are—then the fashion show is an attempt to reassemble these relations in the holographic model of the binary code.