Debating the blinkered Hollywood take on race in films like The Help and Rise of the Apes only helps perpetuate it

Positive or negative, reviews of a new film are surprisingly consistent. Though reviewers may disagree on a thumbs-up, thumbs-down level, they typically highlight the same issues, describe the film in the same way, talk about the same performances, and so on. It’s rare that reviewers don’t discuss a film in terms of its marketing. When a film engenders a lot of argument, odds are that critics are arguing against its marketing and missing what’s actually going on with it while, well, helping market it themselves.

Accordingly, there has been a huge amount of “debate” about The Help, revolving around the ridiculously useless question of whether it’s racist. Of course it’s racist: It’s white Hollywood taking on racial issues. The producers, the director, the writer, and the marquee star are all white. It’s based on a novel by white writer Kathryn Stockett. Am I saying that a white person can’t address racial issues in the civil-rights era without being racist? No, but I am saying that a whole gang of white people with a $25 million budget and a bunch of cameras can’t.

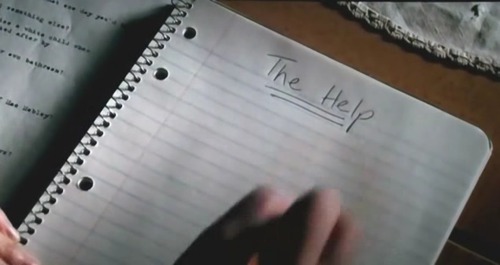

Don’t believe me? Here’s the first shot of the film:

Yes, those are Emma Stone’s white hands writing The Help.

This is the movie letting us know from frame one that this is a movie about white people telling a story about black people.

The movie focuses on Skeeter (Stone), an aspiring writer and member of the social elite in Jackson, Mississippi, circa 1963. She gets testimony from her cohort’s black maids, in particular Aibileen (Viola Davis) and Minny (Octavia Spencer), in order to publish a book (also titled The Help) telling their story in their voice and revealing the everyday cruelty of the petty rich white women who employ them. This, we are given to believe, will empower the maids and help them discover their identity. “No one’s ever heard the story from this perspective!” Skeeter beams to her white New York publisher. The main dramatic tension lies in whether the maids will overcome their fears of violent reprisal and participate in the oral history.

On a historical level, this is atrocious. Both the rich young white women and middle-aged black maids seem oddly distant from the civil-rights movement that is burning all around them. Medgar Evers’ murder occurs during the film’s time span, but none of the protest and action surrounding it is even mentioned. The film depicts the actual black politics of the time as significantly less important to the maids than Skeeter’s efforts to empower them. In a scene late in the film, the maids are applauded by the black congregation at their church for their bravery, and indeed it is, we are shown, an empowering experience. But individual empowerment is meant to be enough, especially as the film ends with Aibileen’s being fired: She gets psychological uplift, but her social and economic power is actually diminished.

Many “serious” critics (David Edelstein, David Denby) like this film, glossing over the historical myopia to focus on Viola Davis’s incredible performance, but a number of criticshave also cried foul. Most prominent among the film’s detractors, the Association of Black Women Historians released a statement slamming the film for the use of black dialect, the lack of attention to sexual harassment faced by domestic workers, and the revival of the mammy character.

But this critique is too limited, attacking stereotypes that the film doesn’t entirely embrace (The Help’s maids are not exactly the mammy figure; though they are portrayed as matronly and asexual, these characters are not Gone With the Wind caricatures) rather than the film’s systemic racism. Yes, only a white person could write the line: “Fryin’ chicken just tends to make you feel better ‘bout life,” but a black actress has to deliver it. And these black actresses do an incredible job, earning every word of praise the critics have given them. But the film’s still racist as fuck. And the black actresses and workers who made this film have to confront this criticism, forcing them into an impossible situation: either defend it as not racist with a willed act of cognitive dissonance, or become dismissive of their own creative output.

Though the maids are given serious screen time and some psychological complexity, the unmistakable fact is that they are still less complex than the white women. We watch the white women laugh, socialize, fall in love, work, achieve, dream, collapse and face crisis. The black women either suffer at their duties, describe their suffering for Skeeter’s book, or display their wisdom and strength in overcoming this suffering. Though no longer mammies, the black women remain objects of history, depositories for suffering and struggle, stand-ins for the entirety of racist injustice, while the white women have complex, real(ish) lives. The black characters, as always in white popular cinema, must represent all of black America.

And no matter how well they perform here, how many starring roles are coming for these not-exactly-Hollywood-beautiful black actresses? When will they ever get this much screen time again? Yes, starring in a hit film and receiving heaps of praise will advance their careers, but not nearly as much as it will help Emma Stone’s. (She is already on the cover ofVanity Fair.) These actresses are complicit in producing a racist work, yet it is the best opportunity they will have to work so well so visibly, to express their creativity and their art to the greatest number of people. By attacking The Help for being racist without considering the economic realities of its production, critics reinforce this racist labor relation.

Still, a majority of critics liked this movie, Viola Davis will get an Oscar nod, and everyone’s gonna make a bunch of money. The debate over the The Help’s race problem has only helped it on its way to being a huge hit: It has made $97 million in three weeks. If selling movie tickets was all the phony debate accomplished, well, there are worse things to do with your time. But the critics’ accusations of racism end up perpetuating the exploitative and racist labor relations. Driving up ticket sales sends money to the white producers, who get new pool houses along with a huge hit on their résumés.

—

August’s other hit film, also widely praised by the critical establishment, appears to discuss race issues in a very different way. Rise of the Planet of the Apes, is, of course, about race war. Movie revolutions fought on hard species lines (usually robots, but sometimes sentient animals) most often resemble slave uprisings or anticolonial struggles—the revolutionaries begin as slaves, dispersed within the population, doing its undesirable labor. But as they become aware of their enslavement, they turn on their oppressors (humans), crush them, and develop their own free state. These movies usually center around the brave human resistance against the evil robot/chimp/what have you new overlords. On its surface, Riseturns this structure on its head.

In Rise of the Planet of the Apes, James Franco (and that’s who he is in this movie, James Franco) is a scientist in San Francisco developing a cure for Alzheimer’s. He tests it on chimps, and it makes them supersmart, meaning that it works. But the smartest chimp, Bright Eyes, goes apeshit and tears up the lab, forcing Franco’s boss to shut down the project and kill all the chimps. (Un)Luckily, Franco smuggles Bright Eyes’s son Ceasar (who has inherited his mother’s superior intelligence in the womb) home to raise him.

The first half of the film is a multicultural family drama, with a mixed-race couple (Franco marries an Indian primatologist played by Freida Pinto) raising their super-intelligent chimp baby. But when Ceasar attacks their neighbor, he’s sent to a Dickensian primate-holding government facility—basically chimp jail. There he realizes the nature of species antagonism, doses the rest of the apes with the drug that made him smart, and leads a daring escape, climaxing in a battle with the police on the Golden Gate Bridge. Ultimately, thanks to the dual processes of mutual aid (freeing the chimps from their cages, feeding them cookies) and propaganda (dosing them with Franco’s brain gas) the chimps unify and overcome their oppressors, ultimately defeating the cops and arriving at their freedom in the Redwoods.

Throughout, the film makes direct references to the African American struggle. The opening scene, in which machete-wielding Africans chase CGI chimps through a jungle to send them to American labs, could be straight out of Amistad. The jailers spray Ceasar with a fire hose to pacify him, echoing images of Birmingham, 1963. But none of these allusions constitutes critique. This film, more than any blockbuster I’ve seen in a long time, plays directly into the deconstructing habits of lefty filmgoers, letting them congratulate themselves for picking up on the racial undercurrents and revolutionary organization taking place. Political theorist Jodi Dean, in a dubious piece of promotion, wrote, “Watch it for the tactics.”

This is hardly a subversive approach to the movie. It is not as though the producers used the imagery of the fire hose or the slave hunt accidentally, and they certainly anticipate that we’ll get off on watching an underclass go up against the cops and win: The scene on the Golden Gate Bridge was the focus of the film’s previews and advertisements. Even our indignation at the connection the film clearly posits between black identity and monkeys feels overdetermined, expected. The apes are the good guys, for chrissakes! It’s a neat trick: If you make a rousing summer blockbuster that allows for a certain amount of smug critical masturbation, you’ll get great reviews for no added cost.

Beyond the civil-rights overtones, the actual implications of the film’s plot are less laudable. In the final scene, Franco catches up with the apes and asks Ceasar to come home. Ceasar replies, “Ceasar is home,” after which Franco tearfully turns away, nodding, to leave him to his new life. The takeaway: the rebellious group, defined by age, race or species, just needs its own home where it can be free, and then it will stop fighting against society. The goal of political action is not total freedom from political oppression but rather the pseudo-freedom of self-defined community within the state apparatus. The Redwoods is, as we are shown twice in establishing shots, a national park, although conveniently empty when the apes arrive.

And the hyperreal nature of the CGI apes increases the distance between the audience and the revolutionaries depicted. They are less monkeys than pure cinematic phantasms, animated unrealities, diminishing the presentation of revolt into pure aesthetic signifying. It doesn’t help, either, that the CGI is obviously superexpensive. That level of economic ostentation tends to neutralize any of the film’s possible political connotations.

A key moment in Rise of the Planet of the Apes is one which also functions as a sequel-enabling aside. It turns out that Franco’s gas, while enhancing monkey IQ, also produces a deadly contagious disease in humans. In a mid-credits coda, Franco’s neighbor, infected with the disease, gets on a plane. The implication is that Franco’s creation will wipe out humanity, and the apes will be left to rebuild. In other words, the apes will not bring revolutionary war to humankind, rather humankind will destroy itself, and the apes will build over the ashes.

—

On a superficial level, each of these films provide different ideas about overcoming oppression. Rise of the Planet of the Apes pictures organization toward violent class struggle. That makes it much more fun to watch then The Help, where speaking truth to power is the major tool to freedom. But ultimately, their messages are the same: Victory occurs upon the achievement of identity empowerment. In both films, the ideological underpinnings are identical. A white person provides the tools, knowledge, and opportunity for members of the underclass to develop and recognize their own identity. The economic, physical, and psychological repression we are shown in both films is ultimately a function of mis-recognition of the consciousness of the oppressed: the struggle for recognition of that paradigm. Thus, once a certain amount of identity control has been wrested, the political project is presumed to be complete.

It is important to see how Hollywood political narratives mirror dominant political narratives, how they inform ways of thinking about politics that drastically limit possibilities. The organizational methods differ between the films, but in a political-historical narrative, it’s the goal that ultimately reflects ideological position. Washington Democrats may want to maintain the current distribution of wealth and power technocratically with slight adjustments, while the Republicans would prefer to throw the people off a fucking cliff, but neither party acts toward or wants an actual reorganization of the current paradigm. Rise up or speak out. As long as you’re not looking to actually overthrow systemic inequality, you can be a hero. If you saw both Rise and The Help in August, and many did, the most devastating mistake would be believing you saw two different forms of political thought.

Willie Osterweil is The New Inquiry’s film editor and a writer living in Brooklyn.