Why doesn't Hello Kitty have a mouth? Is its absence more than an expedient, minimalist design choice? And does her lack of a mouth necessarily translate into the absence of a voice, as the arguments tend to go? The first Hello Kitty product, after all, was a coin purse with HELLO printed in block capitals over an image of Kitty; her name is her form, and it is speech.

Most political engagements with Hello Kitty have taken the mouthlessness issue as their impetus. They generally, through subversion or perversion, ironize Hello Kitty's apparent inability to speak, suggesting her lack of expression is being upheld as a model, particularly for the young Asian girls who form Hello Kitty’s immediate target audience. A woman's value, this particular feminine feline's lack of mouth seems to say, is contingent on her voicelessness.

Jason Han's painting I Haz Mouth, commissioned for the Three Apples exhibition in 2009 on the occasion of Hello Kitty's 35th birthday, whimsically addresses this issue. From the painting's smirking LOLcats reference — LOLcats being a premier example of how giving a voice to the voiceless can be infantilizing rather than empowering — to the reiteration of the mouth in Kitty's speech bubble, Han’s painting seems to invoke feminist and postcolonial concerns about lacking a voice only to wave them away. But I Haz Mouth functions not as a dismissal of the problem but an advancement. Looking past the irony of its title, we can see I Haz Mouth as an attempt to answer the question: If we gave Hello Kitty a mouth, what then?

Han has her answer not with words or language but with an image. Might Hello Kitty react to her induction into the regime of expression not as we might want her to — with a cathartic string of expletives — but by bypassing altogether the problems of language, opting instead to faithfully reproduce her newfound means of expression? Han's painting suggests that Hello Kitty with a mouth would not merely speak imagistically, but that her speech itself would actually just serve to represent her mouth, like a guitar that no longer emitted notes but instead created guitars with each string plucked. Instead of entering the closed circuit of language, Kitty deploys the master signifier: the Word that is the Thing, the Logos. The gap between representing and represented is closed.

And because of the design minimalism that supposedly accounts for Hello Kitty's lack of a mouth, something even stranger happens in Han's painting: The speech bubble begins to look less like a representation of speech and more like a third, incomplete Kitty, with the triangle at the bottom serving as a potential ear. At a very basic level, then, the painting suggests that when Kitty is given the tools of language, she becomes capable only of uttering partial self-representations.

The weirdness of this is compounded by the fact that the mouthless Hello Kitty is actually more expressive. The “!!!” above her head signals something more concrete than the speech bubble with a mouth in it. The mouth "says" an image that refers to a specific, externally grounded discourse, one that's technologically and historically marked and gendered and so on, whereas the lack of a mouth allows for the expression of direct astonishment, which is ambiguous and ultimately uninterpretable.

To read the “!!!” as envy, as though the mouthless Kitty has always wanted a mouth, must be backward, however. The painting suggests that in order to think to express a desire for a mouth, one must already have one — one must already be caught up in the order of language and have surrendered to its demands. Kitty can't want a mouth until she's got one — and when she does, it's what she's reduced to.

***

The claim that Hello Kitty's lack of a mouth is problematic rests on the assumption that she operates principally as a representative object — as a sort of proxy for values or ideas like femininity, Asianness, or childhood — and that therefore Hello Kitty's depiction performs those things, reflecting and enacting the social norms that render women, children, or Asians speechless. Though this idea is widespread, it is a fundamental misrecognition of how Hello Kitty actually operates in people's lives. It fails to account for the work she actually performs.

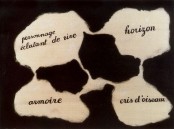

To illustrate this, it’s useful to compare Han's painting with René Magritte's Les Deux Mystères (“The Two Mysteries”). Both incorporate an independent work in order to capitalize on its disavowal (for Han, Hello Kitty, whose mouthlessness functions as a disavowal of speech; for Magritte, his earlier Treachery of Images, with its famous textual disavowal). And both problematize that disavowal (Han by doubling Kitty; Magritte by doubling the pipe).

The usual reading of Treachery of Images is that its joke turns on the disavowal that structures representation — its tagline is funny because it catches us in a natural slippage, and a necessary one in that it allows us to communicate at all. The realistically painted pipe is not a real, material pipe, but we refer to them in the same way, and we don't notice the disjunction unless it is pointed out. We regard the painted pipe as a representative object even as Magritte tells us not to. Foucault suggested that the painted words “ceci n'est pas une pipe” refer not to the pipe above them but to themselves: The words are not “a pipe.”

With Les Deux Mystères, another layer of representation is added. It brackets the disavowal by moving it into a meta-space, making the disavowal a feature of the painting instead of its focus, which in turn enhances the ambiguity of the status of the new pipe. The additional pipe in Les Deux Mystères is untethered, both spatially and discursively. In Les Deux Mystères the large pipe could be on the wall or it could just as easily be floating in the foreground, the smaller of the two pipes. Or it could be a hazy apparition. With even less of a clear connection to the accompanying text, it can't be said with certainty whether it is supposed to be a real pipe, another false representation, or just some sort of literal pipe dream — a dream of a pipe by the not-a-pipe on the easel.

This lack of clarity illustrates the logic of representation, which works by way of seeing-through — by viewers noticing primarily what is beyond what can be seen. For a representational reading of an image to apply, there must be a space between the thing as it appears and the thing as it is (in the broadest sense) “meant.” What is actually seen — on a canvas, say — therefore has to be disavowed on some level to properly understand why it appears there. This is why writing “Ceci n'est pas une pipe” under a painting of a pipe becomes a paradoxical call to immanence. By denying that the painted object is equivalent with what it represents, it forces viewers to focus on the paint instead of the object and therefore pay attention to what is inside and not what is beyond.

Les Deux Mystères extends that call, suggesting that even when we see in terms of representation, we still primarily see the negative: to note, first and foremost, what isn't there or what might exist behind what is. Les Deux Mystères registers and shows the differences, the kinds of gaps that the new elements create, and we ignore the particularities of the pipe in order to abstract it, to determine what it represents.

That is why a direct détournement of Hello Kitty along the lines of Treachery of Images — “This is not a Hello Kitty” — wouldn’t work. Even more savvy efforts (“This is not femininity” ) would only work contextually. Hello Kitty doesn't function according to the logic of representation that Magritte lays bare. “I Haz Mouth,” as well as Hello Kitty in general, operates according to the logic of the icon. Instead of disavowal, what structures icons is immanence itself. Representing nothing, an icon yields fecundity in and of itself, offering itself up to instrumentalization.

This is why when Hello Kitty is introduced into the space of expression, as in Han's painting, her radical refusal to submit to the logic of representation becomes important. Han's mouthed Hello Kitty does not speak words, because putting a hole in her face doesn't mean that suddenly there's something behind; she stays as immanent as she ever was, only now with more lines, her symbolic content slightly altered but never really extended into that third dimension of representing.

***

In Angela S. Choi's 2010 novel Hello Kitty Must Die, we see the possibilities and the problems of an interpretation of Hello Kitty that stays at the level of representation. The explicit critiques of Hello Kitty leveled by the novel’s narrator are fairly common: Hello Kitty is tied to stereotypes of Asian women primarily through her lack of a mouth. But in the novel, these critiques are juxtaposed with events that make them more problematic than they may first appear.

The novel follows Fiona Yu, a 28-year-old Chinese-American lawyer who still lives with her parents, as she navigates her dual heritage. Her struggles with tradition and expectation transform into a story of how she falls in asexual love with a serial killer and becomes something of one herself. Heavily indebted stylistically to Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho and early Chuck Palahniuk, Choi’s novel injects moments of shocking, grotesque, or otherwise surreal violence into a primarily realist frame to provoke audiences to register a limited social critique. But the particularities of Fiona's murders allow Choi to at least gesture toward the possibility that sociopathy might stem from deeper social dynamics than poverty (or wealth).

Fiona's excoriations over Hello Kitty's mouthlessness highlight Choi’s concern with orality and power. When Fiona begins to murder, striking against the oppression of patriarchally privileged bosses and potential boyfriends, she does so in a distinctly oral way. From the roofies she carries everywhere to her scheme to fill her mouth with peanuts and kiss an overbearing loser with a nut allergy that her parents want her to marry, she makes the mouths of her victims into their weak point.

But that kiss never happens, and Fiona's own mouth never provides her with power. The only moment when her own mouth is the focus comes at the end of the novel, through the ritual smoking of a cigarette. Only Fiona's own metaphorical mouthlessness, her tendency to circumvent games of expression and instead attack their source, the mouths of others, puts her in a position to combat oppression. In other words, Fiona is rendered speechless by the dominant culture, and the only avenues of speech are through that culture's narratives. Fiona's story, though, is about weaponizing her speechlessness, receding from the regime of the mouth in order to wage war on it.

***

How can Hello Kitty and her popularity be used politically, if at all? Can it transcend the politics of subversion — a politics that necessarily cedes the ability to create narratives to those who already hold power, contenting itself with minor disruptions — to further instead a politics of generativity? One that, like Fiona Yu, does not seek to avoid its negation but actively weaponizes it.

These two politics do not make up a simple dichotomy, of course. They exist in a dialectical tension with each other, each fraying its counterpart as it reinforces it. To subvert a Hello Kitty, whether one simply subjects her image to appropriation as on Hello Kitty Hell or renders her "betrayal" more overtly elaborate by making her complicit with normalizing sexisms — as in the play Hello (Sex) Kitty, for instance — is to revel in the negation, make it ostensive, and therefore weaponize it. But these détournements never quite, on their own, follow through.

In the quest to ascribe to Hello Kitty political attitudes that can then be deconstructed, her utterly bizarre material existence is too easily forgotten. Stamped onto commodities to make them gifts or collectibles, Hello Kitty serves as the ghost of surplus value that haunts commodities. She is of course not bodied — a no body, an imprint, a bare form, often without even face to save. She is not just a cosmetic afterthought to baubles but a mold to shape them into. And she haunts the children of those maleficent forces who created her, knowing that they will exorcise her — not that she may be freed forever from a purgatorial hell but that she may dissipate into those children and order them to build her again, when they take control of the world, into a new and more powerful form. Hello Kitty's objectivity is infinite precisely because her readiness to betray is infinite.

But here we can see one reason for the impotence of the politics of subversion. The assumption that Hello Kitty is representational misses the point. That's not to say that these critiques and remixes don't have any political purpose or even aren't often wonderful pieces of art in themselves. But they work only within a limited sphere — and not in the sphere of political economy.

If Hello Kitty’s political efficacy is not to be limited by representationalism, we must consider a different definition of realism that doesn’t limit art’s usefulness to its degree of authenticity. In his debate with critic Georg Lukács, Bertolt Brecht defined what is “realistic” this way:

Realistic means: discovering the causal complexes of society / unmasking the prevailing view of things as the view of those who are in power / writing from the standpoint of the class which offers the broadest solutions for the pressing difficulties in which human society is caught up / emphasizing the element of development / making possible the concrete, and making possible abstraction from it.

Realism, that is, won’t be found through the intricacies of parlor-room introspection, as Lukács thought, nor in dirt and grit and Hobbesian cynicism as many believe today. It won’t be uncovered by plumbing the depths any more than by accurately representing the surface; it is only in the dialectical unity of the two that realist art can exist. Which is to say that realism is precisely the realm of the nonrepresentational image.

This may seem counterintuitive: Doesn’t it fly in the face of the reading of Magritte's pipe? Surely the pipe and its disavowal work only because the paintings offer a realistic representation of a pipe. But such objections miss that the real is not merely the representational. To make realist art is not to simply mirror the world but to spray water on the web of social relations that holds the whole thing together. Realism is, at its core, a question of (un)masking what is real, which is to say that which structures reality.

Or, as Evan Calder Williams argues in a post about laughter and realism, “What we need now is a better sense of the real divide to be drawn, between the realism effect and affective realism, between what we've inherited as the 'look' of realism and what actually nails down and pins, like a shaking butterfly of the present, the feel of our historical moment.” That is, a more politically effective realism doesn't just look realistic, like Magritte's pipe, but instead feels real, in ways beyond reflection or comprehension — it feels the way that living under the hegemony of finance capital does.

What Hello Kitty brings to the table in the contemporary search for this kind of Brechtian realism is a metonymic capacity to evoke the amorphous ideas that currently structure the social whole. The first and most obvious of these is globalization, as a result of Hello Kitty's association with the Pacific Rim. Her geographical presence is a series of cleavages: between Japan (concretely) and London (narratively) but also with presence in China through counterfeiters, as well as California and Hawaii, which feature prominently in many of Hello Kitty product lines. Though Hello Kitty can seem fundamentally Japanese, she is not in the same way, say, that McDonald's is American. More than a logo but less than a character, her fractured identity makes her more than a nation but less than truly international, just as globalization is always only a sufficient globalization of capital, not an even and total development.

Hello Kitty also serves as metonym for the process of consumer branding. Ken Belson and Brian Bremner's 2003 book Hello Kitty: The Remarkable Story of Sanrio and the Billion Dollar Feline Phenomenon, relates how founder and CEO Tsuji Sanrio changed his company’s name to Sanrio from Yamanashi Silk Prefecture once he realized the power of branding: “If you attach added value or design to the product, they sell in a completely different way," he said. In her metastasis, Hello Kitty now serves as an evocation of this mystery of how this value is added.

Mark Fisher's essay “SF Capital” provides a short history of the use of branding in science fiction that helps clarify the interstitial space Hello Kitty occupies. Fisher contrasts Star Wars with earlier science-fiction, arguing that “what was bought and sold when audiences consumed Star Wars was not in any sense a single (aesthetic) object, but a world, a hypeThe final quote comes from the text itself and is the co-authors attempt to ironically note the feminist potential of Hello Kitty:

Without quite knowing it, Japan has experienced the subtle emergence of a girl-power movement over the last several decades and Hello Kitty, at the symbolic level, is leading the way. Sure, Japanese men control the political and economic structures and all the trappings of power that come with that, but it is the young, unattached, urban working woman who enjoys the most personal freedom in this highly structured society. She floats from job to job, travels often and typically has the kind of disposable income to buy a Gucci handbag. Hello Kitty and cute or frivolous consumption are about feeling good and carefree. In that sense, Hello Kitty is a menace, a Bolshevik with a bomb, a threat to the established value system.

This sort of feminism, of course, is nothing but the flipside of immiseration, shuffling new subjects into established power structures and leaving them unaffected, except superficially.