Is liking brands ironically on social media a form of click fraud?

Campbell SOUP Company

CAMDEN 1, NEW JERSEY

May 19, 1964Mr. A. Warhol

1342 Lexington Avenue

New York, New YorkDear Mr. Warhol:

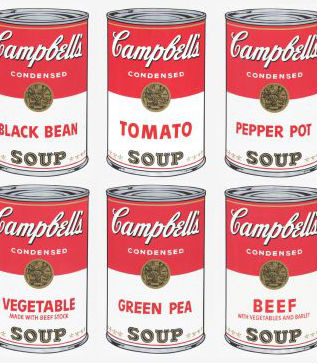

I have followed your career for some time. Your work has evoked a great deal of interest here at Campbell Soup Company for obvious reasons.

At one time I had hoped to be able to acquire one of your Campbell Soup label paintings - but I’m afraid you have gotten much too expensive for me.

I did want to tell you, however, that we admired your work and I have since learned that you like Tomato Soup. I am taking the liberty of having a couple of cases of our Tomato Soup delivered to you at this address.We wish you continued success and good fortune.

Cordially,

William P. MacFarland

Product Marketing Manager

Here comes a whole shipping palette stacked high with Tomato Soup into Warhol’s apartment on 94th and Lex (10 cents a can), while down at the Stable Gallery, there goes box after box painted Campbell’s, each one $400 a pop, tucked under the arms of finely tailored suits and furs. The whole thing is a giant alchemical conveyor belt, turning mass-market dross into high-culture gold. Of course MacFarland admires Warhol’s work—at 36 cans a case, what’s that, a 11,000% markup? That makes the artist the most successful brand manager in the history of the profession. And what’s more, he’s doing it all for free. Pro-bono ad work. MacFarland could weep with joy. Like tomato soup?—the man must love it!

What Warhol liked about these products was at a level of abstraction once removed from what MacFarland’s gesture of sending free soup implied. “I wanted to paint nothing,” the artist confided to his friend Bert Greene about his reasons for choosing the Campbell’s can in 1962. “I was looking for something that was the essence of nothing, and that was it.” A fellow ad-man should have known better than anyone: A brand doesn’t sell a thing, it sells a feeling, an image of a way of being.

Warhol had spilled advertising’s eternal secret: no purchase necessary. That little begrudging bit of legal fine print on every mail-in rebate and contest was, in fact, the most basic truth of the whole commercial universe. The tomato soup MacFarland gave Warhol could feed his silk-screening speed freaks or go straight into the trash. The point is, it didn’t matter; no one actually wanted the thing, what they wanted was all there on the surface, free for the taking to anyone with eyes and an imagination. Buying the product was never going to let you inside the fantasy because there was no inside—beneath the label was nothing but watery tomato paste. In this way, Pop Art was an experiment with the mass-marketed mechanics of surfaces—a glib extension of the Modernists’ high-concept “flatness” into the dimensionless field of advertising and taste.

But even as early as 1964, at his Stable Gallery exhibition, Warhol had begun to push the genre into other, stranger territory. His show had been titled “The Personality of the Artist.” Viewers confronted a gallery filled with dummy cartons of Brillo, Campbell’s, Heinz’s … like the derelict prop room for some supermarket movie set except here it was all supposed to add up to a kind of self-portrait: personality, no purchase necessary. It barely made sense at the time; reviewers ignored the exhibition’s name. Maybe it was supposed to just be another one of Warhol’s put-ons, maybe it wasn’t even his idea. But looking back, the title has an eerie prescience about the future of self-branding. It suggested that the mechanisms of advertising could also become the mechanisms of self-representation and communication; that brands not only insinuated themselves into our lives but that the logic of their circulation could become the logic of our whole social existence. In other words, the exhibition title now looks like an answer that was waiting for the right question to arrive: What exactly is social media?

Warhol’s show might provide the simplest model for describing to, say, a gallery goer of 1964 how a social media profile works today: You’ve got this big blank container, and inside there’s a bunch of logos and brands that you can move around at will building up a commercial constellation that amounts not quite to a person but to a personality. And it’s all free: personality, no purchase necessary.

Anytime between Warhol’s exchange with Campbell’s and the arrival of social media, if you wanted to build a personality with brands, that meant spending money on something like a T-shirt with a big swoosh on it. But sometime in the 2000s, it was as if digital consumers everywhere had collectively gotten the equivalent of MacFarland’s letter to Warhol: We admire your work and we wish you continued success and good fortune. On social-media platforms, brands were disconnected from their presence qua products that needed buying, suddenly skinned à la Pop Art, and made available on the house.

To its champions, social media means greater connectivity among people and perhaps souls—it grows social life horizontally and enables revolutions. Maybe. Whatever the case, our current FacebookTwitterGoogle universe is materially based on the insight that a new digital advertising model could be extracted from a culture already obsessed with representing itself through brand affiliations. It implicated an entire generation of people who already gladly paid for the privilege of adorning themselves with logos and ads in what amounted to a long con. The mystique that once came attached to stuff would now be free—you could choose Nike, Louis Vuitton, Ferrari with a costless click. What’s more, you could forget the wan aura of belonging you could cop from “liking” some brand in public by flaunting goods they sold; now you could show off that a brand liked you.

As in all versions of this con, the magnanimity was only apparent. The providers of connection had hit on an ingenious way of administering customer preference surveys, a way of inside-outsourcing the historically tedious but all too necessary work of figuring out what you personally were most likely to buy. Today your social-media self can kit itself out gratis because, the idea is, that this bundle of brands (personality) can be sold in form of targeted advertising.

For Facebook, the dominant business model is an echo of its beginnings at Harvard as Facemash, which a pimply love-spurned M. Zuckerberg started as a way to compare people’s pictures with those of farm animals. Now we’re all a kind of livestock: a constellation of brand affiliations, tracked, sorted, corralled, through the algorithmic analysis of your likes, keywords in posts and comments, and search and pageview logs. Google, for its part, now makes over 98% of its revenue by selling targeted ads—its Google+ is a kind of Potemkin social network built simply as a pretense to mine and monetize users’ activity across the company’s various properties from Gmail and Google Drive, to Google Maps and YouTube. Its usefulness to customers is totally unconnected to its real function, furthering the kind of persistent tracking necessary to sustain the economy of targeted ads. Personality has become short-hand for a probabilistic model of consumption habits, a speculative commodity bought and sold out the back door of every social media platform.

Out of this field of networked self-presentation and targeted advertising comes a commensurate new form of Pop Art. The new work exploits formal affinities between digital image manipulation and lifestyle advertising—both emphasize perpetual self-improvement as a matter of malleability of surfaces; for both customization is the organizing principle. The contemporary version inverts Warhol’s analogical leveling of fine art and commercial aesthetics: Warhol glorified the vacuous sameness of mass production through repetitive modes of artistic production (superdurational stationary films, silk screens, factory manufacture), while contemporary artists engage the commercial logic of self-customization through the infinitely variable and unfixed processes of digital rendering (digital video production, Photoshop editing, on-demand printing).

The main purveyors of this art have been websites, most conspicuously the art and culture site Dis magazine. Under the sub-header Dystopia, Dis hosts artist’s collaborations like the 2011 project “Contemporary Internet Lifestyles” with the artist Parker Ito, which featured Photoshop-collaged images of a bikini-clad woman using various forms of exercise equipment and cosmetic and relaxation gadgets while simultaneously interfacing with digital screens that displayed stock images of other screen-based devices. Each image lists the brands on display: Sharper Image, BodyForm Total Fitness, Eres, etc.

Last winter, Dis magazine produced a fashion spread featuring the liminal Internet teen star Madison Beer whose career was created ex nihilo from a Justin Bieber tweet that linked to one of her YouTube performances. A typical image (“Faded Glory for IKEA Linnmon/Jegging Work Desk [Back2School Must Have]”) shows Beer with an iPad splayed on top of a desk re-skinned in jeggings, a bottle of Hidden Valley ranch dressing wedged in the heel of her kicked-up shoes. Here, as in “Contemporary Internet Lifestyles”, the strategy of “product placement” is exaggerated to permit an unreasonable proliferation and concatenation of an ever-changing cast of brands, evoking a self defined by its fleeting commercial affiliations. Even—maybe especially—when they don’t feature human models, such images remain portraits rendered in the social media style that Warhol’s Stable show inadvertently predicted. This goes a ways to explaining the repetition of certain other visual tropes borrowed from computer rendering in these images, too—gradients, the glowing diffusion of neons, blank white environs. Jeggings, spandex digitally printed with tromp d’oeil denim patterns, are something of a platonic object for Dis in this sense, having been featured in four spreads in the past year alone. The low-bro pants provide maybe the most convincing example of the genre’s attempt to relocate digital manipulation in material metaphor, the skin-tight simulations standing in for the “skinning” function of computer rendering where a flat texture is wrapped around an underlying skeletal object. In concert, all these references work to funnel representation down into that part of the virtual uncanny valley where identity exists in a vacuum populated by labels and logos, and ruled by the tools of digital manipulation.

The new aesthetic vision of personality as a mutable bundle of branded interests reflects today’s online commercial universe, seen from the perspective of its creators and its profiteers. It need not be affirmative. Embedded in the new Pop Art is a blueprint for subverting social media’s business model. If advertisers typically describe the process of moving a user from a targeted ad to a sale as a referral, the aesthetics of the Neo-Pop suggest a deferral instead, a tantric game of revisable digital self-reinvention.

To understand the destabilizing possibilities latent in Neo-Pop, we can look to the cyber-crime of click fraud. Click fraud takes advantage of the basic payment structure of digital advertising called pay per click (PPC), wherein an advertiser agrees to pay a small fee to a publisher every time one of their ads is clicked, a kind of on-demand advertising fee. Web publishers quickly realized that they could artificially inflate the number of clicks either by using automated programs or by paying fractional wages to people to click on the ads that appeared on their site. A particularly exotic flavor of PPC scam involves surreptitiously installing malware on users’ computers that follows their online purchasing habits and then ex post facto generates fake clicks on ads that could have but in fact didn’t lead the consumer to their point of conversion. Experts estimate that between 10 percent and 15 percent of all advertising clicks may be fraudulent, though those publishers who rely on PPC underplay this figure.

The publishers of targeted ads have an obvious vested interest in both under-reporting and under-policing Click Fraud and have been forced to pay out hefty settlements to advertisers because of it. In 2006, both Yahoo and Google paid millions of dollars in click fraud settlements, the latter upwards of 90 million. In the process of their 2006 legal proceedings, Google commissioned the so-called Tuzhilin Report on click fraud, which remains the canonical text on the problem. The report concluded, “There is no conceptual definition of invalid clicks that can be operationalized.” Elaborating the reasoning behind Tuzhilin in blog post around the same time, Google further disclaimed, “although our servers can accurately count clicks on ads … we cannot know what the intent of a clicking user was when they made that click.”

That social networks may remain free—both costless and infinitely flexible—depends on an assumption similar to the one that underlies PPC: that your digital engagement indicates commercially viable interest. That is, social media platforms presume a link between one’s purported interests as expressed in one’s “connections” to a brand and one’s vulnerability to consuming a similar real product. (Indeed your friends have no different status, as data—under the assumption that these links are uniformly meaningful, they too can help predict what you might buy.) The cost effectiveness of targeted ads is measured by their ability to make such “conversions.” That’s the rapturous finale of targeted advertising, the end of the long con: the Conversion.

Faith in the Conversion had been passed down through generations of ad men, held over from a predigital consumer culture when it was a given and self-evident truth because the only ways to engage with a brand was by consummating its advertorial promise. In the end, it didn’t even really matter why someone wanted to truck with a brand, what mattered was that to do so they had to buy something first.

But the assumption that the Conversion follows inevitably from brand engagement begins to dissolve under the logic of Neo-Pop: Understand that the digital self can be customized ad infinitum and for free, and every shade of interest in a brand can be played with perpetually, isolated from the need for its consummation. Contemporary artists’ mastery of these rules does not amount to an invention—like Warhol’s work, it is merely a disclosure and its intensification. Neo-Pop artists lay bare the basic paradox of their contemporary advertising milieu simply by enlarging the fine print of its underlying premise through aesthetic play. Personality: no purchase necessary.

On a certain well-known artist’s Facebook profile, among the predictable smattering of likes of arts nonprofits and esoteric philosophers are as series of anti-sophisticate brands: Doritos Locos Tacos, Hot Topic, Monster Energy Drinks. If this data were visualized as art, it would belong in Dis. But to the algorithmic eyes of targeting advertising it simply stands as a cue to push coupons for Taco Bell. Might the artist in question use an e-coupon for Taco Bell? It’s as pointless as asking if Warhol ever actually ate the soup MacFarland gave him. What this artist is playing at is the treasonous endgame of personality: no purchase necessary, wherein the system built to monetize free, branded self-customization begins to falter under the extreme extension of its premise. If users are willing to engage in this kind of promiscuous self-representation, there is no telling what they actually want to buy in the end, no way for advertisers to target them effectively.

Social media platforms’ inability to distinguish between nonconvertible from convertible interest in brands is essentially the same problem faced by a Web publisher trying to police fraudulent clicks. A user’s actual intent is submerged beneath a profusion of indeterminate clicks. At some point the resulting cost of mistargeted advertisements may outstrip their value.

Historical modes of anticapitalist resistance were predicated on refusal. If you didn’t want to be exploited in the churn of surplus value then you refused to enter the factory—strike—and if you didn’t like some product, then you didn’t buy it—boycott. Refusal as “staying out” made sense when it left large parts of your life unaffected. But the diffusion of social life into commercial digital platforms and vice-versa makes exercising such refusal more difficult. You could be a social media ascetic—we all know one—but ambiguous brand engagement models a way of staying in that might present the most expedient form of resistance.

This strategy is reminiscent of “la perruque,” Michel de Certeau’s cake-and-eat-it-too scam from The Practice of Everyday Life (1984) by which workers continue to go to their jobs rather than renounce them, but surreptitiously substitute their “real” work for personal work. (A perruque is a wig, a disguise, a trick.) Just as la perruque reverses the labor-value equation by fooling the employer into paying for laborers to generate their own good rather than corporate surplus, the social media game of deferrals relies on hyper-participation to upend the consumer’s supposed false consciousness.

In the thick of the post-WWII boom, Herbert Marcuse wrote that capitalism sustained itself through a culture industry that stimulated desires for consumer goods that we neither really needed nor could afford. Played out over social media, no-charge personalization grabs hold of the proliferation of artificial desires and uses them freely—literally and metaphorically. Through a kind of short-circuit manufactured desires start to drain value rather than add it. False consciousness turns out to be a problem for the system, not its subjects. With all these computers running full speed trying to figure convertible desires from passing jokes, errant clicks, voyeurism, curiosity, and full-on deception, false consciousness turns into a slur for artificial intelligence.

Given enough time, though, any system will wise up. Anything can become predictable. This will be soothing for a digital marketing executive to reflect on in such troubling times. Let a place like Dis spin its wheels long enough, and ideally their specific antitaste will settle into a trough of predictability. Then it’s only a matter of time before the algorithms catch up. Smirnoff didn’t care if people were buying drinks to mock the stupidity of the brand, and digital advertisers care even less why some set of interests map onto some set of consumption behaviors as long as they can make that map and rely on it. As soon as a promiscuous aesthetic idiom limits itself to a certain cluster of references or (anti-)tastes, it becomes identifiable as style and recuperable as marketable data. Connections cease to appear subversive and arbitrary and become reliably convertible as status signifiers. Thanks to Dis et al., jeggings ads are probably already being swapped out for MacBooks.

Something like this happened when a New York magazine fashion editorial popularized a compact theory based on personality: no purchase necessary that the artists/brand consultants at K-Hole came up with. They called it normcore, “the freedom that comes with non-exclusivity … Normcore capitalizes on the possibility of misinterpretation as an opportunity for connection.” The idea was that embracing mass taste might actually represent an enlightened resistance to the demand to seek out “innovative” ways to be different. Spirited play in the cultural mainstream could lead an end run around personality as symbolized social difference. Then New York magazine went to work on it. The codified version that emerged, a proper style, basically just meant white kids showing up to gallery openings looking like Jerry Seinfeld: outré Nike gear, L.L Bean fleeces, khakis with white socks. A set of specific tastes marketed for those in-the-know. A heady theory streamlined for Internet aerodynamics, a cakewalk for targeted advertising.

Maybe we’ve started Spam World War II without even realizing it. The first war is still raging between a dark army of venal engineers and our white knight gatekeepers—Google, Facebook, Twitter. The former spends all its time trying to come up with algorithms that mimic human speech and behavior well enough to sidle up against the real thing and hock fake Viagra and Nikes, while the latter keeps trying to build better and better filters to keep the Turing Testing riff-raff out.

This second war is like a crazy fever-dream version of the first where everything has gotten screwed up and turned inside out. We—or our prosthetic personalities—become the spambot army pushing nonsense brand names any which way. Soon enough our social media guardians will realize they’ve got mutiny on their own ship. They’ve spent so much time and money on trying to keep your digital life spam free, because that’s what you said you wanted and now you’re churning it out from the other direction. This is why you can’t have nice things goddamit.