It is easy to mistake what we do online as centrally about exposure and transparent exhibitionism. The explosive popularity of Pinterest — a social network based around collecting and sharing “beautiful” images — seems to suggest just the opposite: Rather than reflecting the naked truth of ourselves, we also embrace something a bit more pristine. Wandering on Pinterest can prompt a disorienting vertigo, a dizzying sugar high, with so much that is adorable and clean and sweet. Other networks, like Instagram, can similarly hurt the teeth. When digitally connected, we are increasingly scrolling beautiful.

Instead of thinking of social media as a clear window into the selves and lives of its users, perhaps we should view the Web as being more like a painting.

On the walls of many wealthy 18th and 19th century European palaces were hung so-called picturesque landscape paintings. Disarmingly charming, these paintings, by such artists as Claude Lorrain and J.M.W. Turner, often depicted central Italy and were admired for their beauty; indeed, they were painted to be more beautiful than the landscapes themselves. In 1792, English artist and cleric William Gilpin wrote about the distinction between that which is beautiful when viewed in person versus that which is best captured by its representation: "the most essential point of difference between the beautiful, and the picturesque [is] that particular quality, which makes objects chiefly pleasing in painting."

Gilpin’s essay struggles to capture the aesthetic essence of “picturesque” but makes clear that distinction between beauty as it naturally exists as opposed to constructed beauty. What is beautiful to the eye in the ephemeral stream of (mostly) unmediated experience may be different from what is beautiful in its mediated, documented form. While photography was invented well after Gilpin’s essay was written, many of us have had similar experiences of a photo imbuing additional beauty that one might not have appreciated without the photograph. This is the essence of the picturesque: something that is more pleasing in a mediated representation.

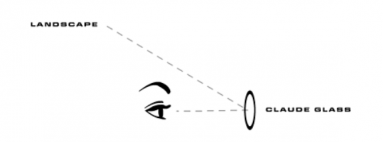

So popular was the picturesque ideal in the late 18th century that it set off a type of tourism in which wealthy vacationers took to the European countrysides in search of landscapes reminiscent of picturesque paintings. Given how the picturesque privileged constructing beauty over appreciating scenery in its natural form, some tourists carried with them a device designed to allow them to view landscapes as if they were picturesque paintings. It was sometimes called the “black mirror” or, more commonly, the Claude glass, named after Claude Lorrain. The device was typically pocket-size, with convex, gray-colored glass. When viewers looked into it, the convex shape pushed more scenery into a single focal point and the color of the glass changed the tones to be more pleasing to the eye by the standards of the contemporary picturesque paintings, which had a limited color palette. The constructed image was thought to be even more beautiful than reality.

What’s most striking about the Claude glass was how it was used: Tourists would stand with their back to the landscape and look at a reflection of it rather than look directly at the landscape they had traveled to see. The Claude glass may be a long-forgotten piece of technology, but in that regard it's a perfect metaphor for much of the modern Web. Imagine the tourist using the Claude glass, turning away from the world and toward a gadget providing an idealized image. And now consider us, positioning ourselves precisely away from the complexities of reality and staring into our glowing, well-connected digital Claude-glass screens.

This is contrary to the belief that the Internet means the end of anonymity, the death of privacy, or the development of a space that requires pure and naked exhibitionism. As we do offline, our self-presentations online are always creative, playful, and thoroughly mediated by the logic of social-media documentation. The Claude glass metaphor describes an Internet that’s more than beautiful — one that is picturesque.

You may have already noticed that picturesque paintings of the past look hauntingly like the faux-vintage Instagram and Hipstamatic photos propagating social media streams today. Less a matter of capturing an accurate representation, the faux-vintage photo uses similar lighting and coloring cues that the picturesque painters employed centuries ago.

Like Instagram, Pinterest is a social network defined by the picturesque. It captures not the users’ reality but instead bathes them within a stream of adorable, immaculate, charming, and precious photos to scroll through, click on, repin, and appreciate. On typical pinboards, the full palette of reality — the ugly, the gritty, the dark, and the complex — is rounded into a version pleasing to the eyes.

But the popularity of Pinterest, like that of the Claude glass, goes beyond the simple enjoyment of pretty images. The wealthy 18th century tourists enjoyed more than just the view, the reflections, and the paintings. More fundamentally, they enjoyed demonstrating their refined taste, distinct from the lower and middle classes as well as the new rich.

And this is how we use Facebook, as well. Many of Facebook’s commentators and users, however, have reified the myth propagated by Zuckerberg that the site “is the story of your life” and “who you really are.” This isn’t the case: You know that your Facebook profile is more beautiful, clever and interesting than you really are; blemishes downplayed and mistakes deleted. There, your Friday night seemed more exciting, your insights more witty, your home better furnished, your film selections more exotic, your pets more adorable and your food more delicious. The myth of “frictionless sharing” exposing everything about the real you is debunked the moment you introduce the friction of turning “private listening” on in Spotify when listening to Bon Jovi.

On Pinterest, we do not collectively fail at creating a “real self” as we do on Facebook. The curated Pinterest pinboards of perfectly prepared cupcakes, flawless bathroom designs, and precious haircuts make no claim to represent the full complexities of reality or self-identity. And Instagram, too, makes obvious an image-mediated unreality that’s precisely the opposite of Facebook’s claim to be the sum of one’s whole life. The fantasy escapism of Facebook is less honest. Facebook is where the fiction of the picturesque is often passed off and regarded as fact.

Simply, if Pinterest is the picturesque landscape painting hung on the wall, then Facebook is where we pretend the painting is a window.

Remember that Zuckerberg’s bank account hinges on pretending Facebook is fact. His data on us is only as valuable as it is accurate. Commentators get mileage out of falsely claiming the “death of anonymity” because sensationalist scare tactics garner clicks, eyeballs, attention, and — again — money. And we propagate the myth out of fear of seeming inauthentic against the obvious evidence we are all posers.Facebook is a lot like identity performance offline — our online and offline identities were never that separate to begin with. We propagate the myth of identity as being natural, authentic, and spontaneous and forget what thinkers like Erving Goffman and Judith Butler have painstakingly illustrated: Identity, on and offline, is a performance. Both Pinterest and Facebook evoke the Claude glass of past and the logic of the digitally picturesque — the beauty of what is constructed, modified, performed rather than given. The mistake is not in engaging in fantasy but buying into the illusion of the real.