Among a small but loyal cadre of readers, Elaine Lee and Michael Kaluta’sStarstruck is regarded as one of the unsung classic comic books. The series originated in the great comics renaissance of the 1980s, during which creators took advantage of relaxed government regulations produce challenging works aimed at a more mature audience, yielding series like Moore and Gibbons’Watchmen and Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. While not as famous as those works,Starstruck nonetheless amassed a significant cult following amongst fans and industry pros for its narrative complexity, experimental storytelling techniques, and gorgeous, vividly detailed artwork. The series bounced from publisher to publisher over the years, from the magazine Heavy Metal to Marvel’s Epic line for creator-owned works to a brief and abortive stint at Dark Horse Comics. Eventually the creators were forced to move onto other projects, and the series languished in a state of incompletion for two decades. Fortunately for both its existing fans and those who missed the party the first time around, IDW Publishing has begun a reprint of the series, currently available in the newStarstruck: Deluxe Edition, with the intent to publish the series in its entirety.

In the mean time, Lee and Kaluta both have amassed a number of critically acclaimed works. Lee is well known for co-creating with artist William Simpson the series Vamps, as well as for writing on the Clive-Barker-created horror comicSaintSinner. Kaluta’s artwork had been held in high regard long beforeStarstruck, with celebrated runs on the anthology-horror title House of Mysteryand the 1980s revival of pulp-character The Shadow. But Starstruck is both creators’ magnum opus. It began its life as an off-Broadway play written by Lee, at the time an Emmy-nominated soap-opera actress, who designed the two lead roles for herself and her sister. A lifelong fan of science fiction, she constructed the play as an affectionate parody of familiar topoi and stock characters within the genre. The sisters befriended Kaluta, who offered his artistic services as a costume and set designer on the production. The play was low budget and limited to two sets, with costumes and props inventively cobbled together from a variety of found items. Its principal characters would introduce themselves by alluding to various events that had befallen them, as well as to characters they had encountered during these adventures. After rights issues made performing the play legally impossible, Lee and Kaluta decided to continue the story in a different medium. They expanded those elaborate backstories into the series, creating an epic saga whose events span decades and galaxies.

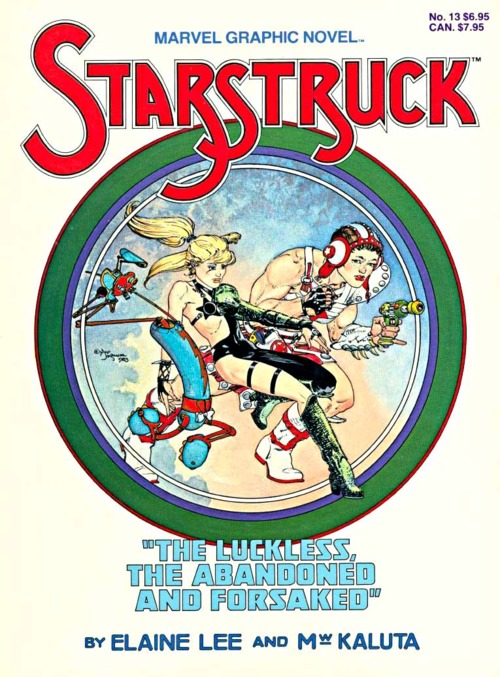

The story is set in the far future after a nuclear war has left Earth devastated and partially uninhabitable. Humans have become diasporic, spread out over several galaxies and colonized worlds, frequently encountering alien life. Several space dynasties have risen and fallen, the last of which, under “The Great Dictator,” led to a protracted and bloody civil war. In the wake of this, the colonized galaxies have entered the “AnarchEra,” an interregnum period in which, at the story’s opening, there has been no determinate leadership for nearly a century. The power vacuum has led to two major dynasties vying for power—the Bajars, who claim sovereignty as the Great Dictator’s descendants, and the Medeas, who are the party primarily responsible for overthrowing the previous regime. The bulk of the action centers on Galatia-9, the middle child of the Medea clan turned swashbuckling space amazon, and her partner Brucilla “the Muscle,” a rowdy but gregarious pilot formerly of the Bajars’ space brigade. After a harrowing meeting at a recreational space station in which they both narrowly escape death, the two women go into business hauling cargo. Along the way they encounter an erstwhile pleasure droid whose growing self-awareness earns her a position as resident science officer, an order of ditzy psychic nuns, and the Galactic Girl Guides, a band of grifter girl scouts who roam anarchic space earning merit badges for larceny and deception. Eventually, all of these characters will be swept up into the machinations of the Medeas and the Bajars in one way or another, leading up to an obliquely foreshadowed event known as “The Great Change” that has far-reaching implications for the entirety of human civilization.

At the time of the series’ initial publication in 1982, the American comics industry was mostly limited to superhero books released by the “Big Two” publishers, Marvel and DC Comics. This had been the case since the congressional hearings into the industry spearheaded by Senator Estes Kefauver that led to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority in the late 1950s. Now defunct, the CCA was an attempt at MPAA-style self-regulation by the industry, which resulted in severe limitations on the type of content that could be published. Under its guidelines, graphic depictions of violence, sexuality, or explicit language were strictly off limits, as was any hint of moral ambiguity in the protagonists. With its lack of racy content and kid-friendly morality, the superhero comic was practically the only genre left standing by the 1960s. Yet the Code significantly hampered even those narratives at times, often in draconian and nonsensical ways. In one infamous example, Marvel had an antidrug story in one of its books rejected because the story mentioned the existence of drugs, at the time a major no-no under Code policy. Eventually, the government scare passed and comics were left to their own devices. By the 1980s, the advent of Direct-Market distribution to comic book stores meant that the fear of inappropriate material reaching children via newsstand distribution was unjustifiable. Suddenly, there was a surge of independent comics aimed at adults, willing to experiment with style and content, which drew influences from a variety of sources including film and the comics of Europe and Japan.

Starstruck was very much at the forefront of this movement. Unfettered by the sanctimoniously proscriptive morality imposed by the CCA, it was free to tackle sexuality in ways that were previously taboo in American comics. This ranged from Kalif Bajar falling in love with a headless sexbot to Kalif’s father’s satirically awful sex advice. As noted by critic Robert Rodi, Starstruck was one of the first titles to acknowledge characters along the LGBTQ spectrum, albeit in somewhat subtle ways. (In particular, villainess Ronnie Lee Ellis’ obsessive fixation on her nemesis Glorianna has some decidedly sapphic undertones.) The series also took a nuanced approach to moral quandaries. As befits a story set in an anarchic universe, Starstruck is a picaresque space opera in the vein of series like Blake’s 7and its spiritual descendant, Farscape. The ladies of Starstruck lie, cheat, and steal their way out of trouble. They are not above pulling short cons on other space travelers for quick capital or dodging the law when the heat is on. Even their ship, the Harpy, is more or less stolen. At times, our heroes can be selfish, callow, immature, and just plain dumb, much like actual humans. But they were also free to grow and mature in ways that corporate-owned comic-book characters could not and still are not. They could also be pretty ruthless. Famously, a sequence involving Galatia-9’s slaughter of a particularly nasty band of rape-prone space hillbillies in an early installment caused some alarm for Marvel’s editorial staff. The moral grayness and explicit content of Starstruck was more than just a departure from comics conventions. The series also represented a darker contrast to the bright and shiny heroics of mainstream science-fiction works like Star Wars, which had recently become the top-grossing film of all time.

Naturally, a story of more complex ideas necessitated a more complex structure to transmit them, and Starstruck was also a major innovator in terms of comics narratology. In the early ’80s, American comics were, for the most part, still very conservative in terms of style and structure. The narratives tended to be linear and episodic in nature, told from the perspective of a single main character. Starstruckwas more like a novel in scope, taking its cues from postmodern prose authors like Thomas Pynchon, to whom Lee dedicated the first collected edition. Each installment of Starstruck was a chapter in one long, ongoing narrative, making it the forerunner of many of DC Comics’ Vertigo properties like Sandman and Vaughan/Guerra’s creator-owned Y: The Last Man. There are scads and scads of characters, many of whom are involved in complicated schemes against one another, against other governments, and sometimes against themselves. In a departure from the objective, exposition-style narration of its predecessors, flashbacks and narrations in Starstruck become a means of exploring the vagaries of human perception. In keeping with the postmodern influence, the comic has a biting streak of absurdist humor. Over the course of the published issues, readers would encounter a Star-Wars-style dogfight in space fought with scrambled eggs, revolutionaries from the planet Guernica who waged guerilla warfare on bad art, and a sibling rivalry among the heirs to the Bajar Empire which eventually escalated into sabotage, multiple assassinations, and the founding of a sham religion.

The series is perhaps most famous for the fact that most of its principal cast is female, which was unusual at the time for any medium, but particularly for comics. Prose science fiction had undergone its own feminist revolution in the 1970s, thanks to authors such as Joanna Russ, Ursula k. Le Guin, and James Tiptree, Jr. (a pseudonym for Alice B. Sheldon), but sci-fi in other media still had a ways to go before it could catch up. The cleavagey sexpot who existed to titillate took a ribbing in the form of ex-pleasure droid Erotica Ann, who, despite her intellect and status as the Spock-like stoic of the cast, couldn’t seem to rid herself of the Marilyn Monroe-esque bimboisms in her programming. Brucilla filled the archetype of the rowdy, boozing, promiscuous hotshot pilot normally reserved for men, and preceded Battlestar Galactica’s Kara Thrace in doing so by about 20 years. And as an anarchist punk spaceship captain who was arrested in her youth for defacing public property with feminist revisions of nursery rhymes, Galatia-9 was a Riot Grrrl before the movement existed.

Notably, Starstruck also departed from many of the conventions of feminist science fiction, much of which at the time was being devoted to myths of isolationism. Many of these stories focused on feminist utopias from which men were excluded or driven into extinction as well as on societies where the battle of the sexes had finally devolved into literal warfare. The tribe of “Omegazons” with whom Galatia-9 briefly allies read as pastiches of several stories about all-female societies; like the Amazons of Greek mythology, they remove a breast in order to become better archers, and their ongoing conflict with the Dromes calls to mind Joanna Russ’s “Whileaway” stories. But Lee deliberately eschews the separatist narrative and isn’t above mocking the knee-jerk misandry which often colored those stories. Instead, our heroine is forced out into the universe at large, where she is confronted with the task of helping to build a society more congruent with her ideals.

The vast universe its characters inhabit is one of Starstruck’s chief delights and possibly its most innovative feature. Of course expansive world-building is nothing new in comics: The superhero genre in particular thrives on the interconnectedness of the characters in its fictional universes. Yet many of those stories pay only cursory attention to the larger world outside of the characters.Starstruck takes more of an inmersive, maximalist approach by frequently alluding to various works of literature, art, songs, plays, and religious scriptures that only exist within the fictional world(s) of the narrative itself. This technique is not just limited to the comic itself but extends to the various back-up texts included with the series, which purport to be actual documents from after “The Big Change.” Examples include the frequently hilarious glossary, which delivers droll commentary on the “historical” events of the story while filling in details about the main narrative, as well as excerpts from the autobiography of Dwannyun of Grivaar, an aspiring conqueror of worlds whose efforts are frustrated by crippling mental illness. Such experiments with hypertextuality had previously surfaced in prose works of science fiction such as Norman Spinrad’s satirical sci-fi novel The Iron Dream or, most famously, Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide series, butStarstruck is one of the first instances of the technique being applied in comics. These sub-texts were more than winking references; they foreshadowed major events in the main narrative and, in keeping with the theme of unreliable narrators, called attention to the ways people construct histories. Alan Moore would later go on to employ similar narrative devices in works such as Watchmen and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to marvelous effect, but it is worth noting that Starstruck was a major forerunner in this regard.

While Lee’s groundbreaking writing draws a lot of deserved attention, it should be noted that Kaluta’s artwork was equally revelatory. The aesthetic of Starstruckdrew extensively upon the visual vocabulary of European comics, particularly the intricate draftsmanship of Moebius’ science-fiction landscapes and the casual sensuality of Enki Bilal. The rich, elaborately detailed atmosphere Kaluta created for the characters is one of the hallmarks of the series and one of its key assets. The Starstruck universe took the opulent art-deco futurism of Golden-Age science-fiction works and combined them with the “Used Future” aesthetic that had been so recently pioneered in films like Soylent Green and Alien. The result was the feeling of a Golden-Age-style science-fiction future that had gone to seed, an empire in a significant state of decay. Poring through the pages of Starstruck we are given the sense of what happens when the utopian visions of an E.E. Smith or Hugo Gernsback start to crumble.

Lately, modern comic-book artists have embraced the “decompression” trend of splash panels and panoramic visuals in an attempt to emulate the fast-paced, wide-screen action of Hollywood blockbusters. Kaluta’s art focuses on the spatial properties inherent in the comics medium itself, namely the fact that the reader ultimately controls the pace at which the story flows. With this in mind, Kaluta takes a visually dense approach to storytelling, in which seemingly minor events or details going on in the background often serve as counterpoints to the foreground images. These details serve as harbingers of major plot developments, in addition to showcasing recurrent motifs or thematic symbols. It’s a stylistic choice which practically necessitates multiple readings and perfectly facilitates Lee’s writing style.

As Mike Carey and A.J. Lake note in their introduction to the collected edition,Starstruck often feels like a work very much ahead of its time; presumably, this worked against it in the end. Comics like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns rode the Cold-War zeitgeist to its end, channeling the fatalism and existential dread of the Reagan years into indelible artifacts of their time, while works like Hellblazer offered a similarly trenchant commentary on the dreariness of Thatcher’s England. Starstruck wasn’t as bleak as those works; in a sense, the comic’s triumph was imagining a world in which we actually survived the ’80s.

Starstruck could be both silly and smart, was progressive but unpretentious, and clever but not so impressed with itself that it ever forgot to entertain. IDW’s reprint of the series is a service to fans of science fiction, aficionados of comics as an art form, and anyone who loves a good story. Kaluta has redrawn some of the pages, fixing the famous “square art” formatting issue from the Dark Horse edition and adding even more detail to many of the scenes. Lee Moyer, who grew up a fan of the series when it was originally published, has embellished the entire run with his coloring, making Kaluta’s artwork pop like never before. Lee revised the glossary, making it snarkier and more informative. The Galactic Girl Guide spin-offs about a young Brucilla wheeling and dealing her way through the galaxy are also collected here for the first time and include several stories that never saw print. The result is a truly definitive edition of Starstruck, one that is better looking and more complete than ever. And there are still two thirds of the story left to go. Maybe we’re finally ready for it this time.