An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

The deep infiltration of digital information into our lives has created a fervor around the supposed corresponding loss of logged-off real life. Each moment is oversaturated with digital potential: Texts, status updates, photos, check-ins, tweets, and emails are just a few taps away or pushed directly to your buzzing and chirping pocket computer — anachronistically still called a “phone.” Count the folks using their devices on the train or bus or walking down the sidewalk or, worse, crossing the street oblivious to drivers who themselves are bouncing back and forth between the road and their digital distractor. Hanging out with friends and family increasingly means also hanging out with their technology. While eating, defecating, or resting in our beds, we are rubbing on our glowing rectangles, seemingly lost within the infostream.

If the hardware has spread virally within physical space, the software is even more insidious. Thoughts, ideas, locations, photos, identities, friendships, memories, politics, and almost everything else are finding their way to social media. The power of “social” is not just a matter of the time we’re spending checking apps, nor is it the data that for-profit media companies are gathering; it's also that the logic of the sites has burrowed far into our consciousness. Smartphones and their symbiotic social media give us a surfeit of options to tell the truth about who we are and what we are doing, and an audience for it all, reshaping norms around mass exhibitionism and voyeurism. Twitter lips and Instagram eyes: Social media is part of ourselves; the Facebook source code becomes our own code.

Predictably, this intrusion has created a backlash. Critics complain that people, especially young people, have logged on and checked out. Given the addictive appeal of the infostream, the masses have traded real connection for the virtual. They have traded human friends for Facebook friends. Instead of being present at the dinner table, they are lost in their phones. Writer after writer laments the loss of a sense of disconnection, of boredom (now redeemed as a respite from anxious info-cravings), of sensory peace in this age of always-on information, omnipresent illuminated screens, and near-constant self-documentation. Most famously, there is Sherry Turkle, who is amassing fame for decrying the loss of real, offline connection. In the New York Times, Turkle writes that “in our rush to connect, we flee from solitude … we seem almost willing to dispense with people altogether.” She goes on:

I spend the summers at a cottage on Cape Cod, and for decades I walked the same dunes that Thoreau once walked. Not too long ago, people walked with their heads up, looking at the water, the sky, the sand and at one another, talking. Now they often walk with their heads down, typing. Even when they are with friends, partners, children, everyone is on their own devices. So I say, look up, look at one another.

While the Cape Cod example is Kerry/Romney-level unrelatable, we can grasp her point: Without a device, we are heads up, eyes to the sky, left to ponder and appreciate. Turkle leads the chorus that insists that taking time out is becoming dangerously difficult and that we need to follow their lead and log off.

This refrain is repeated just about any time someone is forced to detether from a digital appendage. Forgetting one’s phone causes a sort of existential crisis. Having to navigate without a maps app, eating a delicious lunch and not being able to post a photograph, having a witty thought without being able to tweet forces reflection on how different our modern lives really are. To spend a moment of boredom without a glowing screen, perhaps while waiting in line at the grocery store, can propel people into a This American Life–worthy self-exploration about how profound the experience was.

Fueled by such insights into our lost “reality,” we’ve been told to resist technological intrusions and aspire to consume less information: turn off your phones, log off social media, and learn to reconnect offline. Books like Turkle's Alone Together, William Powers's Hamlet's Blackberry, and the whole Digital Sabbath movement plead with us to close the Facebook tab so we can focus on one task undistracted. We should go out into the “real” world, lift our chins, and breathe deep the wonders of the offline (which, presumably, smells of Cape Cod).

But as the proliferation of such essays and books suggests, we are far from forgetting about the offline; rather we have become obsessed with being offline more than ever before. We have never appreciated a solitary stroll, a camping trip, a face-to-face chat with friends, or even our boredom better than we do now. Nothing has contributed more to our collective appreciation for being logged off and technologically disconnected than the very technologies of connection. The ease of digital distraction has made us appreciate solitude with a new intensity. We savor being face-to-face with a small group of friends or family in one place and one time far more thanks to the digital sociality that so fluidly rearranges the rules of time and space. In short, we’ve never cherished being alone, valued introspection, and treasured information disconnection more than we do now. Never has being disconnected — even if for just a moment — felt so profound.

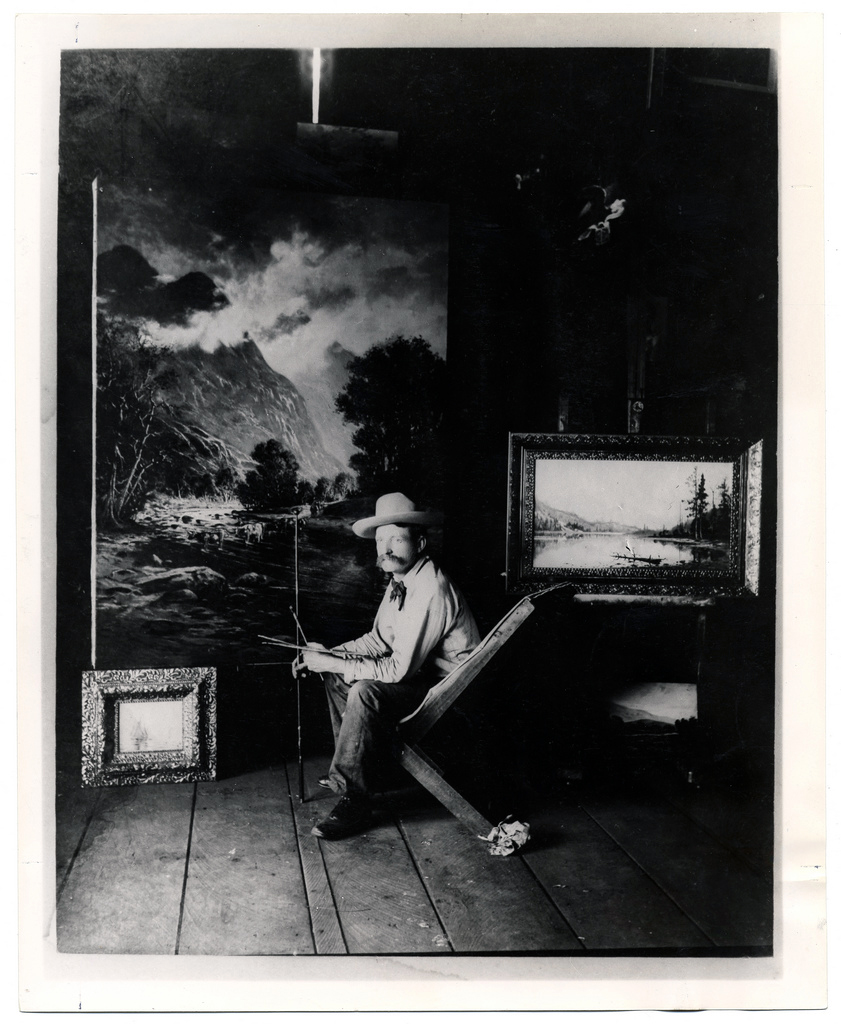

The current obsession with the analog, the vintage, and the retro has everything to do with this fetishization of the offline. The rise of the mp3 has been coupled with a resurgence in vinyl. Vintage cameras and typewriters dot the apartments of Millennials. Digital photos are cast with the soft glow, paper borders, and scratches of Instagram’s faux-vintage filters. The ease and speed of the digital photo resists itself, creating a new appreciation for slow film photography. “Decay porn” has become a thing.

***

Many of us, indeed, have always been quite happy to occasionally log off and appreciate stretches of boredom or ponder printed books — even though books themselves were regarded as a deleterious distraction as they became more prevalent. But our immense self-satisfaction in disconnection is new. How proud of ourselves we are for fighting against the long reach of mobile and social technologies! One of our new hobbies is patting ourselves on the back by demonstrating how much we don’t go on Facebook. People boast about not having a profile. We have started to congratulate ourselves for keeping our phones in our pockets and fetishizing the offline as something more real to be nostalgic for. While the offline is said to be increasingly difficult to access, it is simultaneously easily obtained — if, of course, you are the “right” type of person.

Every other time I go out to eat with a group, be it family, friends, or acquaintances of whatever age, conversation routinely plunges into a discussion of when it is appropriate to pull out a phone. People boast about their self-control over not checking their device, and the table usually reaches a self-congratulatory consensus that we should all just keep it in our pants. The pinnacle of such abstinence-only smartphone education is a game that is popular to talk about (though I’ve never actually seen it played) wherein the first person at the dinner table to pull out their device has to pay the tab. Everyone usually agrees this is awesome.

What a ridiculous state of affairs this is. To obsess over the offline and deny all the ways we routinely remain disconnected is to fetishize this disconnection. Author after author pretends to be a lone voice, taking a courageous stand in support of the offline in precisely the moment it has proliferated and become over-valorized. For many, maintaining the fiction of the collective loss of the offline for everyone else is merely an attempt to construct their own personal time-outs as more special, as allowing them to rise above those social forces of distraction that have ensnared the masses. “I am real. I am the thoughtful human. You are the automaton.” I am reminded of a line from a recent essay by Sarah Nicole Prickett: that we are “so obsessed with the real that it’s unrealistic, atavistic, and just silly.” How have we come to make the error of collectively mourning the loss of that which is proliferating?

In great part, the reason is that we have been taught to mistakenly view online as meaning not offline. The notion of the offline as real and authentic is a recent invention, corresponding with the rise of the online. If we can fix this false separation and view the digital and physical as enmeshed, we will understand that what we do while connected is inseparable from what we do when disconnected. That is, disconnection from the smartphone and social media isn’t really disconnection at all: The logic of social media follows us long after we log out. There was and is no offline; it is a lusted-after fetish object that some claim special ability to attain, and it has always been a phantom.

Digital information has long been portrayed as an elsewhere, a new and different cyberspace, a tendency I have coined the term “digital dualism” to describe: the habit of viewing the online and offline as largely distinct. The common (mis)understanding is experience is zero-sum: time spent online means less spent offline. We are either jacked into the Matrix or not; we are either looking at our devices or not. When camping, I have service or not, and when out to eat, my friend is either texting or not. The smartphone has come to be “the perfect symbol” of leaving the here and now for something digital, some other, cyber, space.

But this idea that we are trading the offline for the online, though it dominates how we think of the digital and the physical, is myopic. It fails to capture the plain fact that our lived reality is the result of the constant interpenetration of the online and offline. That is, we live in an augmented reality that exists at the intersection of materiality and information, physicality and digitality, bodies and technology, atoms and bits, the off and the online. It is wrong to say “IRL” to mean offline: Facebook is real life.

Facebook doesn’t curtail the offline but depends on it. What is most crucial to our time spent logged on is what happened when logged off; it is the fuel that runs the engine of social media. The photos posted, the opinions expressed, the check-ins that fill our streams are often anchored by what happens when disconnected and logged-off. The Web has everything to do with reality; it comprises real people with real bodies, histories, and politics. It is the fetish objects of the offline and the disconnected that are not real.

Those who mourn the loss of the offline are blind to its prominence online. When Turkle was walking Cape Cod, she breathed in the air, felt the breeze, and watched the waves with Facebook in mind. The appreciation of this moment of so-called disconnection was, in part, a product of online connection. The stroll ultimately was understood as and came to be fodder for her op-ed, just as our own time spent not looking at Facebook becomes the status updates and photos we will post later.

The clear distinction between the on and offline, between human and technology, is queered beyond tenability. It’s not real unless it’s on Google; pics or it didn’t happen. We aren’t friends until we are Facebook friends. We have come to understand more and more of our lives through the logic of digital connection. Social media is more than something we log into; it is something we carry within us. We can’t log off.

Solving this digital dualism also solves the contradiction: We may never fully log off, but this in no way implies the loss of the face-to-face, the slow, the analog, the deep introspection, the long walks, or the subtle appreciation of life sans screen. We enjoy all of this more than ever before. Let’s not pretend we are in some special, elite group with access to the pure offline, turning the real into a fetish and regarding everyone else as a little less real and a little less human.

Comments are closed.