Always never read, fine print is capital's surrealist masterpiece, but will we ever wake up from the dream?

It is difficult to say when fine print started exactly. Nobody has written its history, and the details of its past prove elusive online as well. One might expect to find something about its origins in the secondary academic material on the subject, but this, it turns out, looks not to its past but to its future. For these contract lawyers and students of advertising, fine print is already entrenched; if the question of fine print comes up, it’s merely one of reform. As far as primary material is concerned, the problem is exactly the one you’d think: fine print is willfully discrete.

Even the very term “fine print” is ambiguous, concealing this dubious business practice behind a branch of the printing industry. And yet despite this, it is still philology that provides the most promising leads on fine print’s origins. The Oxford English Dictionary dates first usage of the term to 1960, when the historian John Carswell noted of one figure in his book, South Sea Bubble, that “he produced the ‘fine print,’ which it is peril to leave unread.” The South Sea Bubble was an early 18th century speculative market bubble involving the shares of the British joint-stock South Sea Company. Writing about it in 1960, Carswell places “fine print” between quotation marks, which suggests that this, the OED’s first cited example of the term, is actually itself citing an earlier usage. It comes as no surprise, then, that there are uses earlier than this 1960 instance. A 1939 edition of the Detroit Purchasor, for example, carries an article entitled, “The Importance of Reading Fine Print,” noting a case in which “the purchaser thought the claim had been outlawed, but discovered that he had overlooked the fine print provision which waived the statute.” Delving deeper still, we come across the term in an 1892 courtroom testimony recorded The Northwestern Reporter:

Q: You say you never read the fine print over in this policy?

A: No, sir.

Q: Did you ever read the fine print in any of your policies?

A: Well, I have in some insurance companies, where we insure on property, not steam-boilers.

What all these early examples have in common is a particular and general belatedness. They all warn about fine print, but not until the trick has been pulled off and the practice is already widespread. The history of fine print does not become readable until history warns that it should have been read.

Fine print has a habit of eliciting just such a moralizing tone. If somebody is caught out by terms contained in a section of fine print, our first thought is usually that it’s the person’s own fault for being so inattentive, reckless, or even downright lazy. “Always read the fine print.” With its definite article serving at once to distance and to universalize the practice, the old adage is deemed fair warning. And yet fine print asks specifically not to be read. It is a deliberately non-communicative speech act, erasing itself by miniaturization, accumulation, and esotericism. Its first appearance in literature makes light of its use of obscure jargon. Robert Musil, who knew a bit about accumulation too, writes in A Man Without Qualities that the funeral director “pressed into Ulrich’s hand a form covered with fine print and rectangles and made him read through what turned out to be a contract drawn to cover all classes of funerals. […] Ulrich had no idea where the terms, some of them archaic, came from; he inquired; the funeral director looked at him in surprise; he had no idea either.” This passage is taken from Eithne Wilkins and Ernst Kaise’s translation, published in increments between 1956 and 1960. If we return to the original German, however, we find that Musil does not use the literal ‘Kleingedruckte’ but instead chooses ‘Vordruken,’ a term that means something like pre-printed text. Fine print, yet again, presents itself to us as something of anonymous origins that we can arrive at only belatedly. Every early instance of “fine print” smirks nonchalantly as we ransack its apartment, safe in the knowledge that we’re nowhere close to what we want.

It isn’t until 1975 that the term gets another airing in fiction, when Malcolm Bradbury describes a group of sociology professors in The History Man who have “higher criticism to offer, who read the agenda with an energetic scepticism, as one would read a contract from a hire-purchase company, looking in the fine print for errors, enormities, evasions, the entire sphere of the unsaid.” Bradbury’s use of fine print as a mere metaphor seems to have set the tone for its later roles in literary fiction. But in genre fiction, and thrillers particularly, fine print comes into its own as a genuine plot device. In 1993’s The Night Manager, John Le Carré notes portentously that “Burr was too excited to bother with any more fine print.” Lee Child, Jeffrey Archer, and Stephen King all make frequent use of it, too. Perhaps the closest fiction seems to come to decrying the practice of fine print is in John Grisham’s 1995 The Rainmaker, when a character notes that “It’s impossible for any bureaucratic unit to monitor the ocean of fine print created by the insurance industry.” But this, it turns out, is not call to outrage but to opportunism.

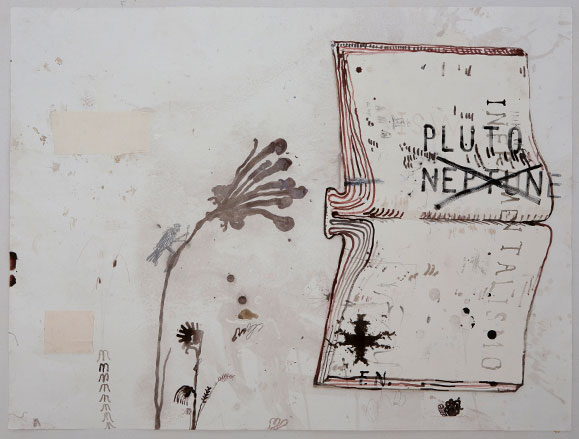

It’s unfair to expect fiction to call attention to the absurdity of fine print, though. “Writing veils the appearance of language,” Saussure notes, “it is not a guise for language but a disguise.” A textual form like fiction must avoid questioning another such textual form lest its own legitimacy be called into question in the process. And so we turn to the visual arts instead, where the key model is René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images. The painting, probably Magritte’s most famous, shows a well-rendered pipe above its own textual disavowal: “ceci n’est pas une pipe” – or, “this is not a pipe.” In the most obvious reading of the painting, Magritte is said to be pointing out the unbridgeable divide between representation and reality. His painted pipe is not an actual pipe. Contracts and (particularly) advertisements that use fine print operate on a similar level. The ad’s loudly stated, carefully worded attractions are representations of a proposed deal, the legitimacy of which the fine print discretely disavows. “This is not the deal,” the fine print says. On the subject of Magritte’s painting, Foucault speaks of an “operation cancelled as soon as performed,” a line that might as easily apply to advertising that offers deals too good to be true. Foucault’s second reading of The Treachery of Images is a little subtler. He suggests that what the sentence “ceci n’est pas une pipe” actually refers to is itself: “this is not a pipe” is not a pipe. In recent years it has become common for fine print to include “unilateral amendment provisions” that entitle the company to change the terms of the deal at anytime as long as they give you written notice. In such cases, the fine print is also referring to itself when it whispers “this is not the deal.”

Our lives are governed by contracts, our minds by advertising; so what does it mean for their respective structures of meaning to so closely resemble that of such a famous surrealist painting? Each instance of fine print constitutes another fragment in the surrealist manifesto that is consumer society, and although authorities try to efface the manifesto by writing it up in tiny letters, the very fact that fine print is a legal and acceptable practice reveals it for what it is.

Fine print opens up a space for fictions without which a society dependent on continued consumption probably could not survive. We live in a society that needs these fictions, as a result of which we too have come to need them. Each ad is a dream we invest in, its lucid elements concealed in the fine print, repressed. Our job is to continue consuming, to consume without retirement, to consume dead labour until the moment we ourselves die. “Behind the dream,” writes John Berger, “are the working people it addresses.” It would be impossible to bear this out without that great multitude of little dreams, which, only deferred in miniature, we are forever compelled to invest in. It is said that when Saint Pol Roux, idol of the surrealist poets, retired each night to slumber and to dreaming, he would hang a notice on his door to say he was “at work.” Today our work consists in simply dreaming, and it is far from clear that we will ever be allowed to wake up.