The Flame Alphabet, Ben Marcus's new novel, takes place in a world where language has become lethal. The main character spends much of the book crafting alphabets, reviving ancient scripts, and inventing new ones ranging from pictograms and runes to fantastic letters made from smoke and air and light, to see if any speech is safe. He wrangles language in unexpected ways in his experiments, trying everything from “administrative script, scripts of love, the scripts used to conceal secrets and deflect attention” to “sentences filled with errors, sentences afflicted with inconsistencies of tense and tone.” But he is essentially a prisoner, searching fruitlessly in a mad scientist’s lab for a nontoxic form of communication.

Marcus’s decision to make his protagonist a scientist of language quite baldly puts the experiment into the term experimental literature. It turns this genre’s label into the genre’s essential subject: What does it mean to be an experimental writer, to do tests? What propositions are experimental writers trying to falsify? What linguistic ailments do their methods seek to cure?

Marcus is no stranger to experimental fiction. The Flame Alphabet is his third or first novel, depending on who’s counting. His first book, The Age of Wire and String, is an encyclopedic compilation of definitions, explanations, and facts from a world in which language has been altered to become unrecognizable. (Its first line: “Intercourse with resuscitated wife for particular number of days, superstitious device designed to insure safe operation of household machinery.”) He next published Notable American Women, a pastiche of confessional memoir, history textbook, promotional literature, and instruction manual. It is an account of growing up on the compound of a female-led “Silentist” cult in Ohio, where a boy named Ben Marcus is the subject of bizarre linguistic experiments.

The Flame Alphabet is in some ways more conventional. It still showcases Marcus’s fascination with jargon: The book’s first page contains a list of devices including “sound abatement fabrics,” “anti-comprehension pills,” a “white noisery,” “a personal noise dosimeter,” and “facial calipers.” Invented or altered quotations and anecdotes adorn the chapters. (“'I would grow mold on the language,' said Pasteur. 'Except nothing can grow on that cold, dead surface.'”) But it also has a unitary narrator, a seemingly reasonable man named Sam, and it’s heavily indebted to the conventions of disaster stories and science fiction. In the novel, a devastating epidemic has struck, disrupting the comfortable lives of the residents of a blank suburban town. Only in place of the typical pseudo-scientific plague, Marcus’s disease is linguistic and overtly meta-literary. Children's speech becomes deadly to adults, and before long all forms of communication turn toxic. Exposure to language sickens; comprehension kills.

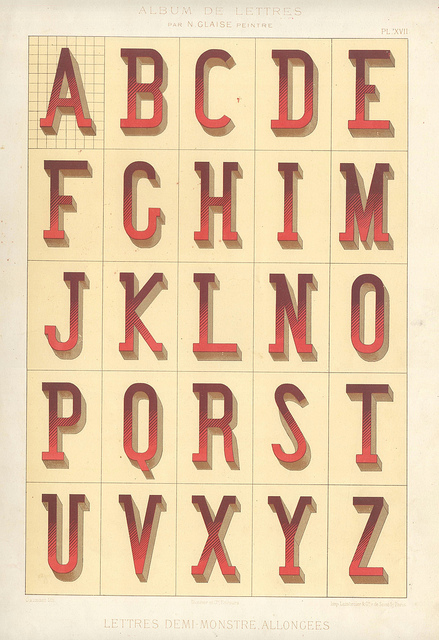

As the disease spreads, Sam finds himself at Forsythe, a post-apocalyptic linguistics lab in Rochester, run by a scientist-crank named LeBov. “Language happens to be a toxin we are very good at producing but not so good at absorbing,” LeBov warns. At the lab, in the midst of total silence interrupted only by bouts of creepy silent and semi-anonymous sex, Sam spends his days testing new alphabets, trying to find a nontoxic way of communicating. He asks, “Did the language itself matter? Was ours exhausted and did an ancient one need to be revived, or were we bound to invent a new one, avoiding the perils of every language that has heretofore existed?”

Sam's question could have been asked at any of many moments in the past hundred-plus years of innovative writing. A longstanding goal of call-it-experimental literature is the revitalization of language. Everyday speech has its own toxicity, this view holds — it has become stale and oppressive, an impediment to understanding. Certain forms of discourse — realist novels and poems, the bureaucratic dialects of authority and business — have been eroded and rendered meaningless, or they are obstacles put in place by power to preserve itself.

Marcus has taken this position against the defenders of the authority of the realist novel. In 2002, Jonathan Franzen went after the “difficult” fiction of writers like William Gaddis as so much status-seeking, preferring works that make a “contract” to entertain the reader. In a 2005 essay for Harper’s, Marcus rebutted Franzen, hoping to “offer another perspective on why a writer might be more interested in the possibilities of language than in the immediate pleasures of a mass audience, more curious about how syntax might be employed to show a reader what it’s like to be alive, to be a thinking, feeling person in a very complex world.” The hope is that writers can reinvigorate language and approach some sort of vital shared humanity. Yet The Flame Alphabet suggests that this is an impossible task — there is no way to extricate language from power relations.

The task of writers is to do what Sam does at Forsythe: play with language, try to find a new way of getting through. Like Sam, the experimental writer is trying desperately to communicate, even when communication no longer seems possible. This idea of literature as testing gives authors the cultural authority of the scientist. But like all disaster stories, The Flame Alphabet at its heart is about the fear of something human beings cannot control, something ultimately beyond the forces of science to handle. In this genre, experiments tend to unleash something really, really bad. By writing this novel as a straight-up disaster story, Marcus aligns language with B-movie tropes: Trying to make meaning from words is as reckless and dangerous as toying with Martian microbes and zombifying bacteria. We should be very wary of those who try to bend words to their will.

There are in fact places in our world where people claim to be able to teach you this kind of control over language. They’re called creative-writing programs. Marcus was the chair of one of the nation’s most influential. Even as Marcus was positioning himself in his Harper’s essay as an outsider, he was taking the helm of Columbia University’s MFA program. The Flame Alphabet, it turns out, is what Mark McGurl labeled a “program novel,” a work that encodes the conditions of its creation within the institutional context of the writing workshop. Marcus’s novel expresses the tension between his identity as a literary wild man and his own institutional position in the creative-writing academy.

In The Flame Alphabet, the interplay of different agendas for language, to communicate and to control, shows an ambivalence about the instrumentality of language. In a recent Wall Street Journal piece Marcus describes the program writer as having mastered certain technologies of language, the skill of constructing “an arrangement of words designed to lodge intense feeling in a reader,” which Marcus teaches in a class called “Technologies of Heartbreak.” There’s a decent dose of irony to such metaphors, which he deploys more elaborately in his fiction. While Marcus's programmatic statements embrace the writer as technician of language, the actual linguistic technologies that appear in his work make creative writing sound like technocracy.

Throughout The Flame Alphabet, Sam uses the word smallwork to characterize everything from his preparation of “speculative medicines” at home to his later language tests to the daily habits of life in solitude. It could also be considered a synonym for the creative writing program’s typical emphasis on technique, process, craft. At Forsythe, Sam uses a device that “broke the act of reading into its littlest parts, keeping understanding at bay.” With his “self-disguising paper,” Sam says he “could write with the perfect impassive remove that would keep me detached from the very thing I was writing.” As Sam tests scripts, he makes himself into a dispassionate, objective outsider, saying, “My own reaction, my own interpretation, my own feelings, for that matter, held little useful meaning for me.” He revises intensely and scrupulously. In other words, he’s a good creative-writing student.

Forsythe’s mad scientist supervillain LeBov, with his inscrutable motivations and dismissive, sarcastic mien, is thus an analogue for a certain kind of teacher. He gives Sam opaque assignments that Sam struggles in vain to complete only to have LeBov mock him mercilessly for not understanding. The person most responsible for the production of innovation in language is also a power-mad, grandiose tyrant.

Sam’s diligent smallwork doesn’t lead to any breakthrough in communication. If anyone in the novel has the kind of power avant-garde writers seek to have over language, it’s Sam's daughter Esther and her cohort, who assault strangers and parents with toxic words. Insofar as Sam has a goal, it’s fundamentally conservative: to restore the previous mode of communication, particularly with regard to father-centered family life. At the book’s close, Sam is alone, waiting for Esther and his wife Claire to return to him, which the reader is led to suspect they will not do. He makes sad plans for the life they will live and says, “This is what we’ll do, as a family.” He indulges the male fantasy of imagining the apocalypse will permit him to become a self-sufficient patriarch, but his need to have power over them assures they won’t return.

By the end of the novel, Sam has become a sort of vampire, hunting for children from whom a fluid can be extracted that gives people safe exposure to speech. The implication is clear: Older generations suck the life out of the young to perpetuate their own language mastery. In the context of creative-writing institutions, the metaphor expresses a real anxiety. People like Franzen, Marcus wrote in his Harper’s essay, “insist that the narrative achievements of the past be ossified, lacquered, and rehearsed by younger generations ... Writers are encouraged to behave like cover bands.” You can call your creative-writing program innovative and experimental all you want and try to resist the role of the authority, but young writers are still going to be subordinated to their older teachers and the teachers themselves subtly limited by the institutional confines. Marcus must fear at some level that he’s caught in this trap — that he wants to be a father and to dictate, rule, and stifle.

To the extent that The Flame Alphabet offers an alternative, it’s mysticism. If writing isn't craft, it's divine inspiration. A divine language beyond human comprehension, related in the novel to an esoteric Jewish cult, might be nontoxic. But it can't be accessed and Sam, unable to solve the problem of language through technology, religion, or human relationships, gets increasingly cynical and longs to be relieved of the burden of speech. As an altered reference to a writing icon has it:

No alphabet but in things, said Williams.

Correction. No alphabet at all.

Marcus, one of the country's most prominent writers and teachers of experimental literature, has written a novel about the dangers of experimenting with language in which literary authorities are deeply implicated in systems of control. The book shows an anxiety about his position as a creative-writing language technician. He wants to cultivate experimentation for the sake of human communication and linguistic possibilities, and to hold out for a vivified language that is not bound up in hierarchies, but has left himself no way to plausibly imagine it. Yet Marcus can't help but insert a possibility that he won't embrace directly — his own irrelevance to the children whose toxic language he can't comprehend, because his being sickened by it is precisely what proves its vitality.

The Flame Alphabet is a novel of generational conflict, in the sense that what the young have to say is terrible, literally sickening, to the old. People once spoke of a generational divide in literature. And there are still Great Male Novelists shaking their heads solemnly at what the kids are up to. What’s odd is how few Esthers there are trying to blast the old guard with their toxic voices. Marcus's disease is both the symptom and cause of this condition. Writing that reenacts the institutional confines that led to its creation still retraces those same institutional boundaries. If the avant-garde is in the classroom, it’s not much of an avant-garde at all.