It is no longer plausible to describe the state’s borders as geographically fixed or the state as distinguishable from capital or “markets.”

In the international industry that has sprung up around border control and migrant detention, Australia has played a leading role. But anti-border activists there have also kept pace with its innovations, mounting effective boycott and divestment campaigns that disrupt the risk management strategies of contractors who attempt to profit from the industry. Angela Mitropoulos is a Sydney-based academic and theorist who has written extensively on the political-economy and financial systems of migration controls and borders. Since the early 2000s Mitropoulos has also been involved in organising and supporting activists projects through the xBorder network both in Australia and overseas. In the last two years Mitropoulos has been working on Cross Border Operational Matters (xBorderOps), a project that was launched in late 2013 following a sharp escalation in the state’s efforts to militarise the Australian border. XBorderOps campaigns for the abolition of the Australian immigration detention system, but its analysis encompasses a view of borders as an international industry for which Australia continues to function as something of a laboratory.

MATTHEW KIEM: Just recently, we have seen the conservative ex-Prime Minister Tony Abbott deliver a speech in London calling on European leaders to adopt more of Australia’s hard-line border policies. This repeats arguments made in April this year by retired Major General Molan (an architect of the Naval interdiction system) following the drowning of more than 900 people off the coast of Libya. In the same period we have seen various far-right groups in Europe – from Dutch anti-immigrant politicians to German neo-Nazis – appropriating Australian government video and graphic propaganda as part of their own campaigns against migration. These are a few of the more obvious or crude signs of how Australia’s border-industrial-complex (BIC) is integrated into an international political-economy of border control. What is your perspective on how Australia’s border control systems have changed in recent years and the significance this has internationally?

ANGELA MITROPOULOS: Xborder has been around since 2000. It was part of the Noborder Network, first emerged alongside De Fabel van de Illegaal and Kein Mensch Ist Illegal within the anti-summit movements as part of an anti-nationalist bloc, and it organised the protests in Woomera (South Australia) in 2002. Though it has been always been project-based, its focus since 2013 has been on the boycott and divestment campaign.

As to Australia, the automatic detention of all undocumented migrants who arrive by boat has been bipartisan policy since 1992. Detainees have been held in a growing number of “offshored” camps, some of which are in the Pacific, and all of which have been run by corporations since 1997. Much of this occurred before Guantánamo Bay, before countries in Europe began detaining migrants on a regular basis, before the “War on Terror.” The salient history aligns with the rise of so-called “neoliberalism,” something of a misnomer since the global turn to stricter border controls attests to the authoritarian dimensions of this period.

That said, it is impossible to understand the global border-industrial complex if we confine our perspective to the geopolitical centre. The border is always a matter of the periphery, boundaries that are seen as both natural and necessary, and increasingly framed as a politics of the in-between shaping the infrastructure of operating systems concerned with the conversion of movements into the form of value. Borders are an interlocking, global apparatus. More so with current efforts at “harmonizing” inter-national border policies, technical integration, and the turn to generic organizational systems across the globe.

Within this history, Australia’s role has been exemplary. With more than $10 billion made available to the detention industry in Australia in recent years, it has been a field of experimentation concerned with transforming volatility into value, the imagination of existential (racial) threat that eludes cost-benefit strictures—and whose effects extend well beyond the conventional domain of migration control. Since it was colonized by the English in 1788 to the present day, Australia has been an experiment in far-flung varieties of European – or, more precisely, the Commonwealth's – borders. It is not simply that Australia has always been a space in which the border is understood as a global project. European fascism has always taken its cues from the techniques of control and subjugation that were previously exported from Europe in the process of colonisation and wars of conquest. For instance, the concentration camp was invented during the colonial wars between the English and Dutch over control of Southern Africa at the beginning of the twentieth-century. Later, the camps were imported into Europe as German National Socialist policy. Among other things, the scope for legitimate violence is greater in the periphery because legitimation hinges on the idea that the supposedly unique qualities of nations, races or cultures are existentially, self-evidently threatened at their boundaries.

A number of Australian figures such as Lynton Crosby, Tony Abbott, and General Molan have travelled around the world peddling electoral techniques and organisational methods “perfected” in Australia: “offshore” or “third country” detention camps, militarised repulsion and interdiction, biometrics and long-range detection. Writing from the US, an Australian journalist remarked that Trump's repeated message in the Republican primaries – “We have lost control of our country. We have lost control of our borders" – made her feel like she was back in Australia. As thousands began crossing the Mediterranean, Katie Hopkins wrote an article enjoining the UK Government to adopt Australia's border regime while gleefully referring to migrants as “cockroaches" and a “virus." There is a global entourage which celebrates Australia's overt cruelty as an exemplar worthy of emulation, racist pride and enjoyment.

As to how the border control systems have changed in recent years, they involve the circulation of shared feelings—feelings of filial, racial bonding—as much as techniques of control, and are increasingly a matter of seemingly abstract codes and formulations, not least of which is the codification of risk. Border controls, irrespective of their paranoid reliance on imaginary threats to racial coherence, are responsive systems. Migration is adaptation and therefore adjustive and tactical. It goes around obstacles and transforms them in doing so. It was along those lines that I wrote “Borders 2.0" to describe current changes as an attempt by border control systems to mime and model the adaptive character of migration, to pre-empt but also convert those movements into a form of value.

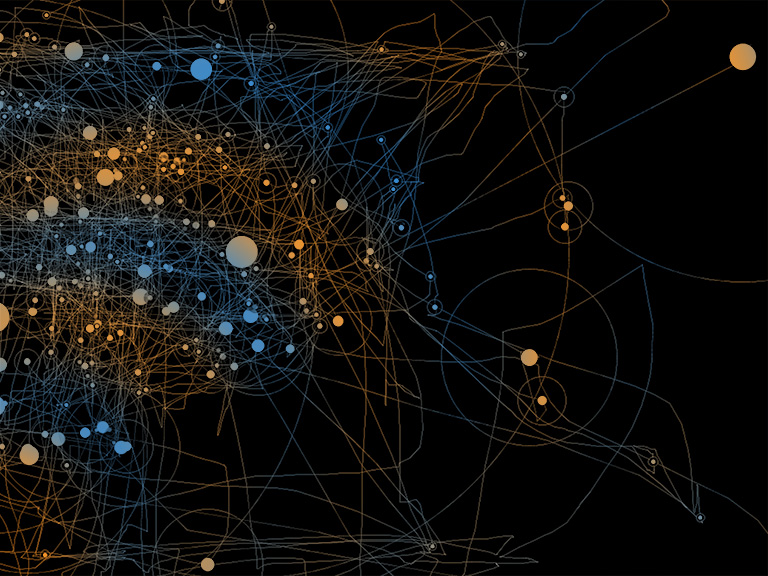

This has involved a spatial but also temporal reorganisation of the border. It is no longer the fixed point but a moving filter between timezones, an extra-territorial (or “offshored”) system composed of hubs and switches, but also mobile techniques of control that adhere to bodies in motion (eg, the behavioural “Code of Conduct” recently introduced in Australia for asylum seekers who will be obliged to undertake a form of indentured labour). European governments have repeatedly tried to introduce a version of Australia’s system of “offshore” detention camps, initially in Libya and now with efforts to strike a “third country” agreement with Turkey to detain and “process” asylum seekers there before they reach “Europe proper.” In “Archipelago of Risk,” I argued that the salient mechanisms of this conversion are less those which Foucault described under the heading of the “carceral archipelago” (with their reliance on statistical probabilities, capacity, and docility) than risk analytics (including among other things: pre-emption, preparedness, non-linear or stochastic modellings of movement and desire). This is perhaps a longer discussion.

In the main, I think it is no longer plausible—if it ever was—to describe let alone theorise the state’s borders as either geographically fixed or the state as distinguishable from capital or “markets.” The way in which states actively create markets in, say, the “people-smuggling” that politicians denounce, and do so by dint of legislation and criminalisation, is but one example. Another is that border control is a kind of “public-private partnership” between states, corporations and NGOs.

So I strongly disagree with those who say the problem with immigration detention is its privatized and secretive character. Privatization alters how we understand and oppose that system. But nostalgia for state-run detention is an impediment to doing both of those things, not least because it involves an appeal to nationalism. It is untrue that “we” do not know or see what happens in detention, or that if the people (the figural audience) did see, then “bad things” would stop happening. Whose gaze is being assumed here? The compulsion to visibility, a voyeuristic obsession with the visualisation of “exotic” trauma or of people of color suffering and victimised, ignores the extent of surveillance that detainees and undocumented migrants are subjected to, undermines the clandestinity and privacy that (undocumented) migrants often require so as to survive, and is often simply the occupational impulse of those whose income is derived from “making the scandalous visible” for a figurative, liberal (and white) gaze. In any case, nostalgia for state-run prisons and detention camps functions as a way to re-assemble nationalist, citizen-based political constituencies. It is not a project that shares the abolitionist, anti-racist premises and aims of, say, long-standing theorists of the prison-industrial complex such as Angela Davis. It is not a project that xBorder supports any more than we would place our faith in the ICC or agencies such as the UN’s International Organization for Migration.

By “Commonwealth's borders” do you mean something like Five-Eyes?

In a way, yes. “Five-Eyes’ is the reincarnation of the English Empire, the filial Anglosphere of global surveillance established after World War II. What Snowden uncovered is how this has grown into a global security apparatus with a broad remit on the “critical infrastructure” of capitalism: telecommunications, energy supply, transportation. Here too the emphasis is on mobile control systems regulating how and where things, data, people move across borders. To think about the border as a filtration device is to raise a question about what it is that it filters for, and this is as much about the distinction between “real refugees” and “economic migrants” as it is about systems of profit and exploitation whose principal mechanism in Five-Eyes is the technological embodiment of the armed, paranoid “Western” gaze.

From what you have said here and elsewhere it seems important to underline the dual function of the border for capital and state actors as both a means to regulate and discipline migrant labour, but also as a multi-billion dollar industry in and of itself. This goes some way towards explaining the interests at stake in sustaining the BIC but raises further questions as to the mechanisms used to transform movements into value. You have cited the concept of “risk” as critical to understanding these dynamics. Can you elaborate on what you mean by this?

There are some obvious mechanisms that convert migration control, indeed racism, into money and profits. In 2009 in the US, and in a context of declining numbers of undocumented migrants, Senator Robert Byrd – who began his career in the Klan and was then Chair of the Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security – introduced a “bed quota.” This meant that ICE would guarantee the capture of more than 33,000 people as part of its contractual agreement with companies such as GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America. Predictably, the numbers of people in detention grew by around 46%, and revenues to detention industry companies have skyrocketed.

On the one hand, this can be seen as a straightforward case of immigration detention being assigned a monetary value. On the other hand, the “bed quota” is a rudimentary mechanism for calculating risk. It furnishes a number from which it becomes possible to calculate the ratio of potential costs and gains. Risk, in its conventional sense, is a calculation of the statistical probabilities of a ratio (losses and gains, both sides of the ledger). It involves the establishment of regularities for investors, makes it possible to ascertain a rate of return on outsourcing contracts, and so on.

The additional point is that if we simply see the problem as one of privatized immigration detention, then we misunderstand how the “bed quota” (as one element of a risk analytic) drives the growth and profitability of the border-industrial complex and, more importantly, gives rise to a border infrastructure that assembles government, non-government and corporate entities into organizational systems. What contracts do is assign risk to the contracting parties in such a way that this risk can be calculated or estimated. This is what the “bed quota” does. It does not only mean that a bed is accorded a dollar value—or, put another way: “money” is not a synonym for “capital.” This is not a slightly more sophisticated system of barter (in which dollar bills are traded for numbers of people in detention) but of capital, where speculations on the rate of future losses and gains are part of mundane reckonings or elaborate formulae—not least where speculation involves the preemptive imagination of racial threat.

GEO Group’s share trades on Wall St are not trades on today’s yields but estimates of future values, made possible by such things as the “bed quota” from which it becomes possible to estimate the future losses and gains of any given investment today. To disrupt into this dynamic, opponents of immigration detention have to stake a position in the imagination of a radically different future, one that does not include the detention industry at all. Anything less will partake of the dynamics of arbitrage, hedging and risk management.

To return to your initial remark about the ways in which border controls are also controls on migrant workers, I was struck by Bernie Sanders’s furious suggestion that open borders was a Koch Brothers’ “proposal.” I am not sure that this is indeed their position, or how acquainted Sanders is with migration struggles. I would think it obvious that some capitalists support the conditional entry of migrant workers, and that these conditions (exclusion from, say, health care or specific working conditions) are in fact mechanisms of border control whose function is to create workers who will work for as close to nothing as possible. Sanders verges on repeating the aspersion that migrants’ bodies are inherently “cheaper” than citizens. He could instead have highlighted how border control methods actively create a class of persons as a fearful, pliant, highly precarious and therefore hyper-exploitable strata of the labour market. It is important to critically foreground these processes of classification and not naturalize their “results.”

If we see border controls as a means for converting and shifting risk, then the exclusion of migrant or undocumented migrants from health care is part of a system that, for employers, minimises the transactional costs and downside risks pertaining to the employment of migrants relative to citizens. If we do not see these processes as complex accounting systems relating to profitability and speculation, as a contemporary form of racial classification, then we drift back to the national and socialist view that imagines borders as a means of protecting workers. There is sentimental support for this protectionist view among socialists, but I see no evidence that borders have been an effective shield against capitalist exploitation.

This picture of a border infrastructure that assembles government, corporate and other non-government entities has been key to how xBorderOps has developed strategies for destabilising the detention industry. This has been framed in terms of addressing the supply chains of the detention industry, an idea that encompasses not simply questions of logistics but also corporate finance and managing reputational risk. This work has been pivotal to the success of campaigns to boycott the 19th Biennale of Sydney over its detention industry sponsorship in early 2014, as well as a recent decision by a major superannuation (pension) fund to divest its shares in detention contractors. Can you explain the impact that boycott and divestment tactics have on the BIC, and why you see this as a strategy with the potential to bring an end to the detention industry?

The boycott and divestment campaigns targeted the value contained in the detention industry in order to destroy that value, whether it is realised as profit or imagined in speculative trades. The largest contractor, Transfield—who just this week rebranded themselves, rather suggestively, as Broadspectrum—verges on corporate collapse. The value of its shares has been halved, they have been driven out of the sponsorship agreement with Australia’s largest arts festival, three pension funds have divested, and since they began managing immigration detention, they have been unable to pay their shareholders dividends. The rebranding was a direct result of the Biennale boycott: the trademark agreement was withdrawn. Serco, another detention contractor, have fared little better. That is one part of the story.

As detention camps were relocated to “third countries” and remote areas, it nevertheless became apparent to some people involved in local noborder networks that we had some connection to the detention industry (through pension fund investments, or a ticket to an arts event), the disconnection of which can arguably have a more immediate impact on the value and profits accrued by that industry or company. We stopped thinking of detention camps as existing in strictly fixed and spatial terms and began rethinking them as financial flows through supply-chains that stretched into mundane parts of everyone’s lives. In this way, the detention industry could become a tangible object of protest at various points where its value was at stake. The ongoing difficulty here is that much of this requires detailed research on complex financial and corporate arrangements—and in a context where the detention industry has implicated and becomes profitable for a range of institutions (including universities, unions and NGOs), the scope for funding independent, accurate research narrows considerably.

Still, the issue in supply-chains for any corporation and government is invariably one of risk management. I do not mean “risk” in the sense that Ulrich Beck uses it (who tellingly defines it as an effect of the erosion of “traditional” borders), but as an financial instrument for ascertaining the ratio between potential losses and gains, and which encodes, among other things, racial panic about eroded borders in abstract form. It is not surprising that Frontex (the European border control agency) states that “Risk analysis is the starting point for all Frontex activities.” Supply-chains are by definition a cross-border system, involving both connections and boundaries.

The managerialist approach to risk emphasizes logistics, the perspective of managers moving things and people around with minimal friction and cost, of optimising flows and of weighing the upside and downside risks of doing business in this industry. On the one hand, in an attempt to save the detention industry from itself, there has been a renewed focus on a “human rights standard” on the part of NGOs and other organisations with links to the detention industry. This is the capitalist response to the protests against immigration detention, and especially the divestment and boycott campaigns. Its aim is to identify and price the downside risk of the detention industry so that this industry might continue. This is not so different to the classical actuarial dream of inoculating capitalism against the uncertainties that it gives rise to (I discuss this in “The Time of the Contract”

Against risk management, we’ve taken the view that the power contained in markets is the refusal to enter into contracts—hence unequivocal boycotts, divestment and disruption. This is another way of understanding a strike when the issue is not (or not only) the addition of a quantum of labour—though, in the case of the Biennale boycott it was in some ways that too—but on processes which add value in a more biochemical, non-linear way, since we are in the realm of “services” and sharemarkets rather than an assembly-line. Even so, the detention industry in Australia is already undergoing a restructuring in response to the strains on its profitability. Whether and how it survives and how we respond to those changes is now a live topic of debate.