Juliet Jacques rewrites the coming-out story that anyone compelled to speak through their identity is demanded to repeat

The first time I met Juliet Jacques was at a video installation at a church in Bethnal Green, East London. We sat on the pews and she told me that she was working on a proposal for a memoir on transgender living, developed out of her column for The Guardian, “A Transgender Journey,” which would follow her experiences of gender reassignment via readings of Julia Serano, the changing edges of the queer scenes in Manchester and Brighton, charity clothes shopping, and a failed audition for 24 Hour Party People. We talked about writing the self and how we would never be Hélène Cixous.

By the time of this interview, Juliet had signed off her book, Trans. I wanted to talk about the ambivalent feelings around making the personal public, and what it means to establish a platform for trans issues in a broadsheet paper when you identify as an outsider. I wanted to begin with the paradox in which, having spent five years writing publically about her identity, Juliet did not want to write or talk about herself now at all.

Exhausted is exactly the word. You can’t feed mostly upon yourself and sustain enough energy to live, that’s always going to be counter-productive. The process of writing about oneself is draining, and comes with a whole set of anxieties, like: how is this going to affect my personal relationships? The paradigm that frames traditional transsexual memoirs – which in my Guardian series was inescapable – was the need to transition against the risk of losing family members, friends, lovers, jobs, social security. Going through the process of transition I experienced all these concerns, and then, in writing about coming out to people close to me, I faced the same anxieties again. In spite of this, on some level I ended up feeling an existential need just to do it.

Writing about oneself can also be therapeutic, in terms of working through stuff – but obviously writing in a journal is different from constructing a memoir. At what point did you start to write as a way to make sense of things?

I’ve kept a journal for the past 6 or 7 years. I did use these journals for writing the memoir, but didn’t enjoy looking back at them. In 2006 in particular I was mentally ill, having a minor breakdown – and the diary is a record of the year at the end of which I began psychotherapy. The journals were meant to work through my psychosis but actually seemed to deepen it. I recently wrote a piece for Granta on Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia) and the process of journal-keeping, and as I said there, my journals are not always reliable anyway.

How did you work through reconstructing moments of your life, disjointed or already altered by memory, into a tell-able story?

In the first draft I tried to treat each chapter as a long-form essay structured out of roughly arranged notes. It didn’t work – the tone was too journalistic, and – maybe because I felt like it was cheating or something – I didn’t talk to anybody about my memories, which I’d thought I trusted. This meant I had no distance, and I couldn’t get under the skin of anything.

In the second draft, I structured the narrative using techniques from screen-play writing and interviewed friends to find anecdotes I’d forgotten. I set out a dramatic structure to work out what the key moments of the narrative would be. At first I thought it felt formulaic, but then I realized I could play around: some of these moments would be dramatic, others more ruminative. For those moments where I was trying to pass in the street and people were giving me hassle and I was inside my own thoughts, I tried to draw on these Nouveau Roman/British neo-modernist novels, set in the protagonist’s head.

The other thing was simply to find the right starting point. It didn’t work to begin with my childhood, because that brings up all these old clichés, like “I knew I was different as a child,” and that kind of thing. It’s not that that doesn’t ring true for me and other people, I’m just bored with the formulation. So I decided to start with the surgery. It gives more of a sense of self, I think. The extra layer – in which I’m writing and publishing these experiences as they happen – is implicit in the form, in that this chapter is lifted directly from the Guardian series. A certain “facelessness” – how I wasn’t able to be “myself” (in any sense of that word) as a child – became more interesting to explore retrospectively.

The book explained much to me about the sense of dysphoria that tends to accompany trans existence – about how one gets to know one’s sense of self and one’s physicality, for instance – and how you negotiated this without language or experience to frame it, at least in the beginning. For the ignorant (cis) reader, your own getting-to-know-yourself is a helpful device for understanding.

One of my favourite passages is where I’m writing about the early internet in 1996–98: going on Ask Jeeves or Alta Vista and typing “transvestite” or “transsexual”, and finding primitive Geocities websites and other people’s life stories. I was finding these photos that weren’t fetishistic or pornographic models of what a trans body should look like; photos of people who weren’t always aiming to “pass” perfectly, people who looked good, comfortable with themselves. It wasn’t very interactive – you didn’t have the same kind of exchange that comes with blogging and social media. But at that point I didn’t want to interact, I just wanted to listen.

In the book you see me find that language, as you say, in a journey that started on the early internet and continued through underground clubs to academic gender studies – writers like Kate Bornstein, Leslie Feinberg, Viviane K. Namaste – when I discovered the notion of transgender. You see me finally getting to this point of self-knowledge, and then the book becomes about what I could try to “give back” in writing about my experiences.

You write in the memoir of a “circular struggle” – a will to stop writing about trans-related issues, but also a responsibility to keep doing so.

I always wanted trans stuff to be part of the fabric of what I wrote, from when I began to accept and acknowledge this as part of my identity; I didn’t want it to be everything but I didn’t want it to be erased either. I got typecast quite quickly – that’s the way journalism works. Audiences and editors want a certain thing from you, and you do have certain things to say on these subjects for personal and social reasons, political reasons. I now have this platform, and it would feel irresponsible not to use it to write about trans issues; on the other hand I justify my writings on art and literature as a form of activism, trying to show young trans people that you don’t have to write exclusively about your identity.

Do you feel like this is a personal closure as much as a public opening up?

Absolutely. I don’t have anything more to say about my Life. It does feel like a closure of the transition itself. There was a big depression at the end of finishing the book, which mirrored the depression I’d had after the surgery, although it wasn’t as serious. It felt like I’d finally ended the transition and moved on, even though the medical side of it wound up a couple of years ago – and it also felt, yes, like the end of a certain type of writing.

So what is the next type of writing?

What I’m working on now is a collection of trans-perspective short fiction set in Britain in the twentieth century. Trans characters written by trans authors are more or less absent from literary fiction, and when you do come across trans characters, they tend to be there to make a setting more exotic, or to serve as a plot twist or a cipher for the author’s opinions about gender. Short fiction means you can catch someone at a particular moment, whereas with longer narratives, there is a certain trans narrative arc which involves the realization of having a gender issue, coming out, and whatever.

Do you feel you’re developing a style for these yet?

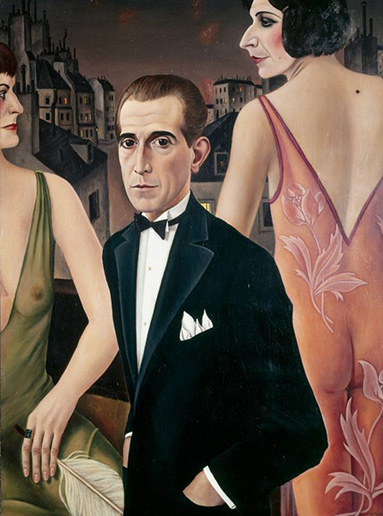

They’re quite often collages of materials, letters or emails, sometimes narrated in a fractured voice. For example, “The Woman in the Portrait,” published in Five Dials, is told by an art critic, and uses the invented diaries of one of the transvestites associated with Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science during the inter-war period in Germany. The character is a fan of Weimar cinema and she wants to be a film star. Christian Schad, who I know did paint a portrait of a trans woman (in Count St. Genois d’Anneaucourt), discovers her in a nightclub, one of only two places in the world she can exist – the other being The Institute of Sexual Science, where she works – anywhere else just isn’t safe. Schad promises to take her out of there, and put her in films, and even paints a portrait of her, but in the end he totally appropriates her body and shuts her out of all the discourse around it.

It’s an extension of the female muse question and that objectification of women, only with an extra level of othering.

Yes, objectification and misogyny – but misogyny that is seen as more acceptable because people don’t consider her a woman. When I presented the piece at the Tate Modern, I didn’t reveal it was fiction until the end, and at first people seemed to believe the diaries were real. I was a bit surprised that no one was like, hang on a minute – the in-depth diaries of one of the first trans-identifiable women have been discovered, and none of us have heard about it?!

I went to a talk recently by gender studies theorist Clare Hemmings about her research on the activist Emma Goldman, and a series of correspondence between Goldman and a woman she had an affair with. They have many of the letters to Goldman but few of her replies. Hemmings was talking about the need for imagination in writing about sexual histories – and what she did, within this historical-theoretical research, was rewrite the lost letters. It seems like you’re also interested in picking up threads of real personas and imagining their stories through fiction.

Yeah, I like this approach, based in historical research, interviews, and newspaper articles; I originally wanted to write a non-fiction trans history of Britain, but found there were too many problems in deciding what definition of trans I would use, or how far back I’d go… drawing the boundaries felt too contentious.

And given that all identity is entwined in a process of invention, if you do it smartly enough, the form of fiction reflects the issues at stake. I picked out this quote from Trans, which speaks to a relationship to time: “Suddenly I was feeling that division just as sharply as before I came out. The transition had done strange things to my sense of lived time, simultaneously making me feel pubertal and prematurely aged, as if I’d existed twice.”

I think I’m talking about a photo I’d seen of myself in Manchester in 2004, where I’m wearing lipstick, I’ve got a headscarf on and I’m wearing a twenties-style dress. I’d somehow forgotten that there was this long intermediary period in which I was moving – not necessarily smoothly, but continuously – from male to female. Other aspects of the transition, like changing my name, made a sharp break in how I was living, which did kind of make me feel like I’d lived twice. Very odd things happened to my sense of lived time.

It must be existentially odd in terms of the recollection of memories – looking back and feeling a disjuncture.

One of the weirdest things was dealing with the change of name as time went on. For example, after I’d come out and was living as Juliet, a friend who I’d known since I was about 15 was telling us an anecdote from several years ago, and there was a bit where he needed to refer to me in the third person. I thought, “What’s he gonna do?” and he went, “Oh and Juliet was asleep and I didn’t want to wake her up.” It felt a bit odd to hear him say that, because that wasn’t who he thought I was at that time. But to have outed me, and used my old pronouns and name, would have felt worse. There have been many of these moments that build up to a jarring sense of a divide.

I’ve always hated being photographed. There are not many photographs of me, I don’t own a camera, even on my phone. But I find that still image, capturing a single point in a duration, really interesting; like Henri Bergson’s ideas on creative evolution, a gradual changing of the discourse of self.

Another thing I hadn’t considered much before reading Trans – linked to the exaggeration of “Before” and “After” images in the media that you write about, and the subsequent disallowal of an actual transition – is the idea of passing as not only a reduction of the spectrum of gender, but an effacement of past selves. I was wondering whether you’d experienced negative effects of leaving a previous self behind.

This was something I anticipated a lot before I began transition. When I was 21, I wrote a short story called “The Invented Past of Marina”, where there were two narratives, one on either side of the page. It was set at this banal middle-class garden party of the kind I got taken to as a teenager, where there’s this passive-aggressive guy small-talking with a woman. He’s asking a series of personal questions, and she’s struggling to invent some answers. The other side of the page is her monologue, thinking: how I do handle these questions? I wish he would leave me alone, does he know I’m trans or not, and if he does what kind of power dynamic is behind these questions? I find it interesting that I’d anticipated these difficulties at a time when I didn’t know any trans people, had only been out as Juliet once or twice, and had very little direct experience of cross-gender living.

When I did begin the transition, I had to come to a position quite quickly of how I felt about passing. In the end I decided that I would only try to pass as a cis woman when it was a matter of personal safety, or in brief transactions in public. Otherwise, I would try to be open about who I was. It’s about balancing the need for openness and a continuous sense of self with personal safety.

There is a sense of relative ease at the end of the book. I don’t know how constructed this is, or how true to how you feel today, but you say there that you sort of miss the flux.

I do. This overarching structure of the transition gave me a sense of direction and an excuse to put other life decisions on hold. “The end” was anti-climatic; it meant swapping one set of problems for another.

There is still life to deal with. The next level of basic needs.

Yes, it’s a hierarchy of needs.

There’s also an overwhelming mundanity in the final scenes.

The mundanity was absolutely necessary. I was working in Charing Cross Hospital and the clinic was over the road. That feeling of dropping back into the office after the final gender clinic appointment. I felt that I should celebrate, and then found that the only option was a really disappointing meal in a pub that didn’t stand up to the occasion at all. What could I eat on my own, in an empty pub playing Aerosmith, that is going to be equal to the final conclusion of this whole process? Fried halloumi and salsa turned out not to be it.