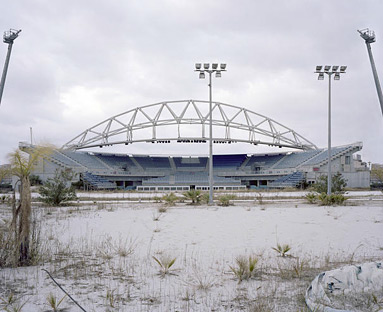

As the fervor of each Olympic cycle fades, what were once teeming public spaces become empty haunts. For architectural photographer Jamie McGregor Smith, nowhere is this more problematic than in the legacy of the last decade’s Athens Olympics. His latest documentary project, Borrow, Build, Abandon, looks at the twenty-two Olympic structures built for the 2004 summer games at a cost of about $15 billion. As Smith notes in the series’ artist statement, of these twenty-two stadiums only three are still in public use eight years later. The others require $100 million a year in upkeep.

The photographs of Borrow, Build, Abandon call to mind the grand landscape paintings of the 19th century, where ruins dot a nearly people-less backdrop. In one of Smith's images, a woman and her children hang laundry to dry on the chain-link fence bordering a stadium’s vast and empty parking lot. In another, a man is just a black speck under the sweeping arches of an outdoor walkway. These photographs are troubling in part because the stadiums’ architecture is contemporary to our time. We spend our days in and among structures that look similar, in cityscapes not too different from the Athens presented in Smith’s project. But the buildings in Borrow, Build, Abandon, the literal waste of an event long over, stand uninhabited: They have become modern relics. Cast in somber gray tones and bearing the mark of neglect — graffiti mars the white façade of one pavilion, while elsewhere an old banner hangs ripped — the Olympic sites have come to represent the cost of national pride as well as Greece’s greater economic crisis.

Rebecca Bates: What makes Greece’s forgotten Olympic stadiums such a perfect metaphor for the pressure of maintaining a national legacy?

Jamie McGregor Smith: Originally I was drawn to them because it was something that hadn’t been documented, and it was important to bring them to light in order to draw attention to a certain failure in social and political design. Not just specific to Athens and the Olympics, but something that could be related to other failures in planning throughout the world in different nations, different cities.

They’re a very good metaphor because of the international nature of the Olympics, and the fact that the buildings are such a public failing, in a sense. You have these big modern ruins; they become a metaphor just in the scale and the fact that everyone can relate to the buildings because they are so modern, and they have similar architecture to the other buildings that surround them. They’re not just old castles that people could then relate to as old history; people relate to them because they see these buildings around all the time. They’re very much in the public limelight.

RB: Obviously, these structures were built to be both attractive and functional, but the photographs are staged such that they are obviously desolate. What did you, as the artist, decide had to be done so that this project didn’t come down to just one political message?

JMS: My approach was quite influenced by photographers before me who have tackled man-altered and industrial landscapes. My approach was always to make the pictures as aesthetically beautiful as possible, and that draws on the same kind of rules and appreciation of beautiful landscape and architectural photography. If you can shoot in that way, it only helps to expand the presence of the photograph, and in doing so that contrast and that juxtaposition makes the message even more powerful in the context of abandonment.

RB: You compare these stadiums to the “factory shells in defunct industrialized cities.” What makes the comparison explicit for you?

JMS: I’ve just been drawing similarities that I’ve witnessed in places like the old post-industrial cities in Midlands, England–places like Sheffield, Newcastle, Middlesbrough. Again, these aren’t ancient relics, they’re relics from the industrial revolution, which I guess only finished probably with the metal mining in the 60s; they are modern ruins. You build such big structures, and yet have no plan to convert them or to change their function into something else. I think the same failure has happened with the Athens Olympics, in that there was no inherent design that these buildings could be modified for use afterwards. There’s a lack of foresight that’s happened in the past with industrial buildings, and that’s visible in the stadiums in Athens.

RB: In the entirety of the series there are so few people who appear. How often did you encounter other people while shooting? Was there a resistance to your just entering these stadiums, or could you walk around unhindered?

JMS: There might have been the odd moment when there were some people in the pictures, or I might have had to wait for someone to leave the picture. But actually I met so few people in these sites the whole time I was there. There was very little security presence and very little public presence, and in a sense these spaces are still supposed to be open to the public. They’re kind of built within public areas, so you can see that big open car parks surround most of the stadiums. There’s public access and public road access to all of them. However, they weren’t occupied by anyone, and I think there was one moment that I met a security guard while I was photographing the Kayak Slalom Center, and he took me off-site, but that was the only time I encountered a security guard. I actually walked straight into the Olympic Stadium without anyone asking me what I was doing there and set up my camera and took pictures and left. No one even blinked an eyelid. But on the whole these spaces were as unoccupied as they look. They were very, very empty.

RB: How then do these stadiums figure into local culture?

JMS: A couple of the big complexes are actually south of city toward the Adriatic Sea and the coastline; they’re quite separate from the city. Athens is constantly expanding, but you almost get beyond the periphery of greater Athens at that point. Then they’re kind of in this no-man’s land between the city and the summer tourist attractions that you have on the beachfront, so there are a few hotels, restaurants, and clubs that are satellite to the main city. Those stadiums sit between the coastline, the port, and the city itself. They’re not integrated into the local population. There’s a metro network that was installed that was designed to bring people into the stadiums. But I think apart from the Olympic Stadium, which is very much set within the city, the others are very much satellite towns that you’d make an effort to move to.

RB: Obviously, in the years and months leading up to each Olympic cycle, the host nation spends a great deal of time celebrating the construction of its stadiums. What then makes a space with an acknowledged limited shelf-life so disastrous?

JMS: For starters the whole issue of energy and materials is on everyone’s mind, and to not have the foresight to think that through is tragic, especially in a time of austerity (and the fact that these buildings are built for only a limited number of people to enjoy, but they’re funded publicly by everyone). It’s quite sad having those reminders around you the whole time. You can be deeply in recession, but you can look back at the Olympics and feel a sense of pride at something that you’d achieved. But I guess if you have these white elephants lying around on the landscape, then it’s only going to remind of you of a failing, and I think that’s quite tragic.

RB: And, of course, as we’ve said, these stadiums have become white elephants in part because they weren’t built with the technology for adaptation. How did you see the London Olympics sizing up in comparison in terms of structural sustainability and peer-pressured national pride?

JMS: I think that peer pressure was definitely still there, and we almost doubled the budget in the end. In terms of the structures, I think London was a turning point. We’ll see it if happens in Rio. I’ve got a feeling because Brazil’s is such an expanding economy and they do have a slight sense of loose change within the economy, possibly, that they might well have a bit more money to spread around, and they might not be thinking about it so tightly. I think in London within the planning we’ve learned a lot from Beijing and Athens already, and I think there would’ve been a huge public outcry if something positive wasn’t done with the Olympic site. Half of the stadiums are only temporary, so they’re coming down straight away. We’re not going to be left with a 30,000-seat volleyball stadium. There are probably only three teams in Britain that are any good at beach volleyball. And we actually had a fairly stable government all the way through. With Athens, they were unlucky because they had a change of government a year or two before completion, so all the decision-making was taken over by a new team. That lack of planning led to the failings you can see now.

I’m optimistic about London. The thing is, property and space are in such high demand, any space or any buildings there will be snapped up straight away. The downside of that is [the Olympic site] was built in an area where there used to be a lot of affordable housing and public housing for possibly low income families and low income workers, and the Olympics has made that area of East London extremely attractive. For example they’re turning the Olympic village where the athletes stayed into affordable housing. We’ll wait and see a few years down the road how many of those apartments will still be available to lower paid workers and families, and how many would have been sold off for double the amount and will now be available to city executives. I think the potential is that poorer and lower-income families will be edged out away from the city and away from those new facilities into cheaper housing on the outskirts of London, which wasn’t part of the initial legacy. So that’s one negative potential. But on the whole, I think we should see a positive legacy from our Olympic site.

RB: Where else, not just with structures meant for the Olympic games, do you see the poetics of space come to stand as a symbol for our cultural or political moment?

JMS: I always go back to manufacturing and industrial sites. Places like the big steel factories in Midlands, Britain. For instance, the big car plants in Detroit: for a long time they were a real symbol of national pride. They were designed and built in an era when they were seen as the future, and they were already futuristic when they were built. Adaptation didn’t occur, and that’s why they became unaffordable to run, and they were closed. For me they’re very symbolic of that post-national pride.

For Britain, steel and ship building was this huge international industry and a real source of national pride. This was a technology that we’d built and developed and mastered. And then, really quickly, as everyone else realized they could do the same, all this work went east to places like Korea, Japan, India, and China. And now you’ve got these vast, vast steel foundries that are completely empty and disused. And for me they’re the most symbolic structures of that industrial change and globalization.

RB: There tends to be, especially when it comes to photography of Detroit, a fetishizing of crumbling buildings and factories. How do you keep your work from lapsing into “ruin porn”?

JMS: It’s something I’ve been contemplating a lot. It’s an aesthetic that’s immediately likeable, and as a photographer you’re drawn to it, especially if you’re someone who is interested in history. For me, the Athens project, and probably the stuff I’m doing in England at the moment on post-industrial cities, is looking at a current political statement and something that people can relate to now, and that hopefully will inspire people who are working in those industries to do something else. And I hope that it’s a maturity away from that ruin porn, as you put it.

In order to look at industrial and social change within photography, you have to look at the past, and that’s when those kind of derelict spaces become part of that project. But you still need to look at how it’s changing and what the future holds, and I think if you can do that as a photographer, try to create a sense of where something might be moving, if you can document all of that and put that together, then your work has a bit more worth than just exploring these places just because of the aesthetics of what years of decay have done to them. Those kind of places, photographers will always be drawn to them and viewers will always enjoy them, but it’s something I am aware of in my work.

RB: So then where do art and documentary merge and diverge? Do you believe photojournalism at face value to be art?

JMS: Remove one image from a photo essay by a photojournalist and it is art because it’s still being created with an aesthetic eye by a photographer. Even if you remove the photographer, the fact that a viewer can like and appreciate it and find meaning makes it a piece of art, even without the context of why it was taken and who it was commissioned by. I find the work that I’m doing now — the kind of work that’s documentary, but it’s thought through and it’s shot slowly and considered, and it’s considered prior to going to the location, and whilst I’m there it’s considered, and then within the pick of the images when it’s put together, there’s another slow consideration — it’s not that kind of fast-paced, action photography you get within reportage and photojournalism on site within a conflict zone. There’s just as much power and just as much truth in that considered documentary approach as there is in capturing that moment within reportage.

Also, and this has been brought up in debates recently within photography, the fact that everyone has camera phones, everyone has an instant way of documenting a moment and then uploading it to a website, it’s slowly going to overshadow the professional photojournalist on commission to document a war zone. In some ways the people directly involved in [a conflict] are going to get just as clear pictures at some point as the professional photographer. So, in a way, a photographer who maybe goes in afterwards or before and documents it very slowly with a tripod in a large format, I like to think that they will become just as important as the photojournalist because in a way they will have more time to actually consider what it really means, as opposed to just capturing this sexy action that’s happening at the time. I think there’s a lot of room for the considered documentary approach in the future.

RB: Why do you think people are interested in photographs of ruins? Is it somehow natural to be fascinated by abandoned spaces, or is that more reflective of our particular moment?

JMS: I think this goes back to the castles-in-the-sand kind of debate. People have always been fascinated in ruins, right back to the classic painter who painted scenes of ancient Roman and Greek civilizations and tied fables and Greek proverbs into these paintings. I think people are always fascinated by remnants of the past. It’s the excitement about discovering something new and something that’s been left behind. That’s a human fascination with exploring and discovering and history. It’s about going in and creating a window and a space that no one else has ever seen before. The photographer will always want to capture something that no one else has captured (even though they’re probably the tenth photographer to go into a big building and document it). That’s the appeal.