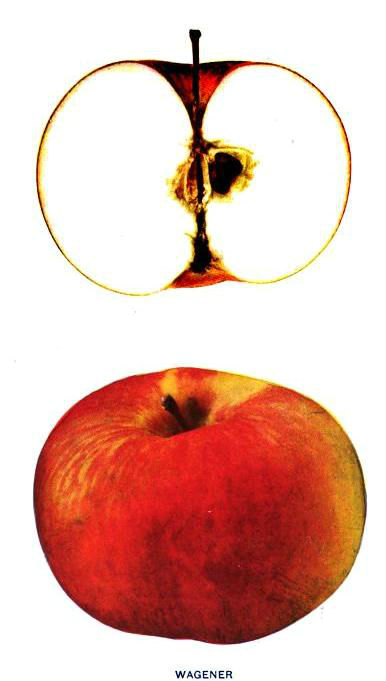

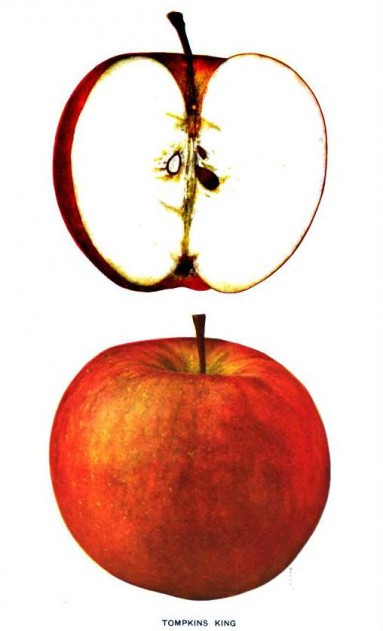

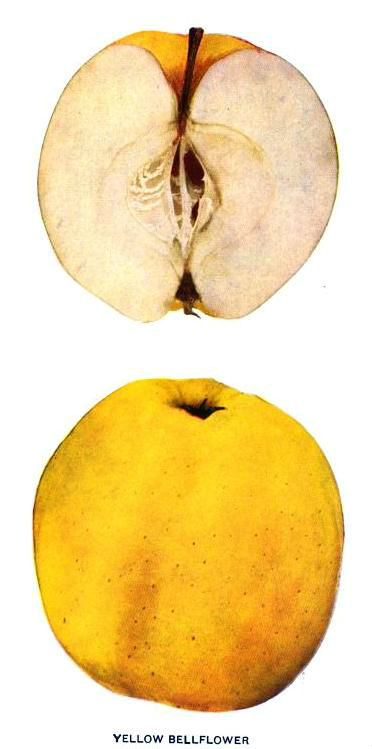

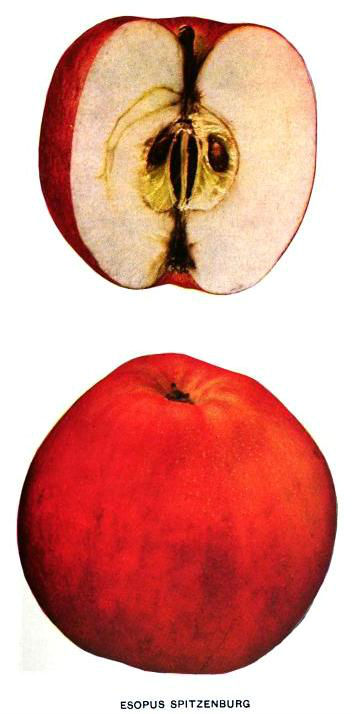

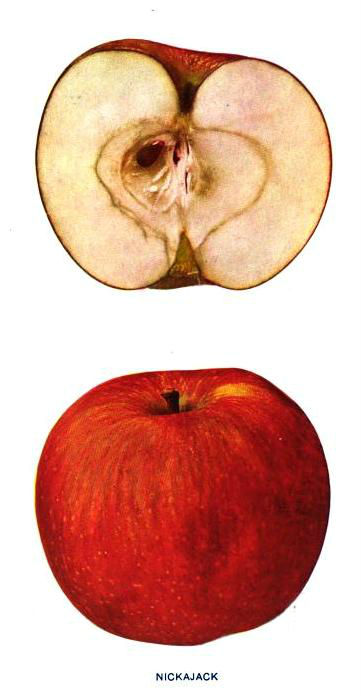

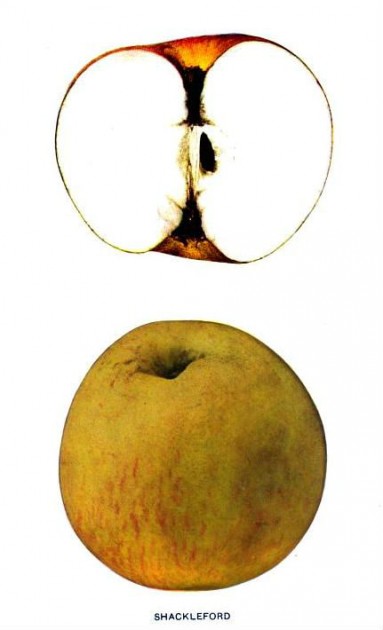

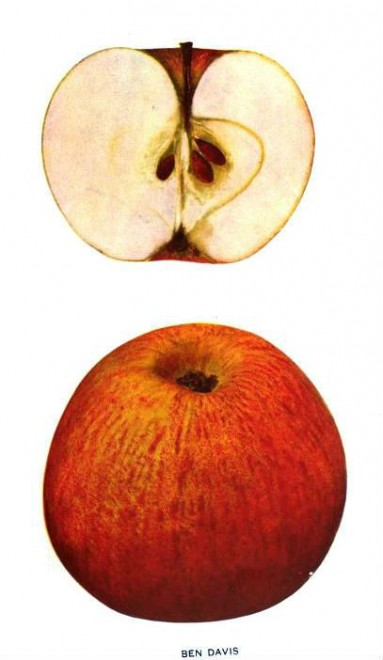

Illustrations from The Apples of New York (1905)

The apple tree was likely the earliest tree to be cultivated.

In 1820 a Quaker nurseryman and farmer in York, Pennsylvania, cultivated a deep red, lopsided apple that he christened "Jonathan Fine Winter." His neighbors savored its sweetness and appreciated its shelf life (it kept through the winter). These qualities quickened demand; Jonathan Jessop's Jonathan became the most sought-after apple in the area. With it the mild husbandman could be said to have struck gold.

The ancestor of the modern apple tree flourished in the mountains of Central Asia. Alexander the Great is credited with discovering dwarfed apples in Kazakhstan.

But such gold lay everywhere in nineteenth-century America. The Jonathan Fine Winter was just one of the thousands of varieties of apples that grew on abandoned colonial farms as well as carefully tended orchards. There was the Abbot's Five-Sided Spice

"Thousands of the Swiss peasants make their entire supper on apples and bread, and thus preserve good health and nourish their bodies well." -- from the Herald of Health (1876)

, a pale yellow-skinned apple splashed and striped with two shades of red, and the Cabbage-Head, a vigorous grower and good bearer whose flesh, though a bit coarse, was juicy, brisk, and decidedly good. The Better Than Good produced a golden fruit speckled a tawny brown, while the skin of the Black Gilliflower shone a dark, dull red, but whose flesh was white and mild. The Foundling boasted a rich red skin and a pleasant vinous aroma, and the Fourth of July made for a good cooking apple. All these and more flourished from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon.

Apple trees grown from seed only produce fruit fit for cider. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century most apples were grown expressly for making this beverage.

Though the only apple tree native to North America is the crab apple, the efforts of John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed, helped to foster the apple's present ubiquity. Born in 1774, Chapman led a nomadic life from an early age. At eighteen he persuaded his half-brother to explore the frontier with him. Together they wandered the wilds of Pennsylvania and Ohio, apprenticing at orchards and subsisting on the land.

"In reading of the miracles of the loaves and fishes to an illiterate family, about a fire where apples sputtered in a spicy row, he had a vision of his orchard multiplied. Then his dark-gray eyes went black and luminous." -- Eleanor Atkinson, Johnny Appleseed: The Romance of the Sower (1915)

Described as an odd character by the people who knew him, Chapman was a devout Swedenborgian who proclaimed the sect's gospel of charity and neighborly love to whomever would listen. He traveled alone, barefoot and clad in sack cloth and a tin bowl that he wore as a cap. He preferred sleeping outdoors. Claiming that he was saving himself for two female spirits who would be his wives in the afterlife, he never married. He loved animals, though, and refused to ride horses and flinched at killing mosquitoes. Native Americans and children he found to be the only trustworthy companions.

"Man alone is a recipient not only of the life of all three degrees of the natural world, but also of the life of all three degrees of the spiritual world." -- Emanuel Swedenborg, Angelic Wisdom Concerning the Divine Providence (1764)

It was said that the farmers of Devonshire and Herefordshire would salute their trees with a portion of the contents of a wassail-bowl of cider, with a toast in it, by pouring a little of the cider around the roots, and by hanging a piece of toast on the most naked branches. The ceremony these farmers finished with raucous dances around the trees accompanied by bawdy songs that they sang at the top of their voices. This they believed would summon forth fruit in overwhelming abundance.

Chapman's unorthodox ways belied a mind for business. Apple trees were his stock and trade. Chapman monitored the movements of any pioneers who appeared on the scene. On land he thought they were most likely to settle he planted apple seeds. Then for the next two or three years he kept watch over these orchards. He surrounded them with fences to keep out livestock and returned every year or two to tend them. Once the settlers arrived, he would sell them his apple trees at five or six cents apiece.

Recipe for Oxford Apples from Apple Growing in California (1914): "Pare, core and quarter four large tart apples and boil in very little water. Mash and add one tablespoonful of butter, half a cup of sugar, half a cup of fine bread crumbs, the yolks of four eggs and the whites of two eggs beaten light. Pour into a baking dish and cover with a mergingue made of the whites of two eggs and two tablespoonfuls of powdered sugar and brown."

Chapman wandered ceaslessly, moving with the frontier. Soon he had an efficient system for tending his orchards. In autumn he returned to them to gather seeds. In spring he scouted sites. In summer he repaired fences and searched for local agents to tend the trees. By the 1830s he had a chain of nurseries that reached from western Pennsylvania through central Ohio and into Indiana. At the time of his death he had planted over one hundred thousand square miles of apple orchards.

Though the exact date is unknown, some say Chapman died in the summer of 1847, while others claim he died two years earlier and in the spring. He left an estate of over 1,200 acres of orchards to his sister, but the financial panic of 1837 devalued his property, and much of his land was sold to pay taxes. His grave remains unmarked, yet gnarled descendants of his apple orchards can still be found, proving that our best works outlive us.