Beyond purely instinctual attraction, at least two things draw me to street art. The first is that despite international crossings of artists, motifs, and even movements since at least the early 1980s, graphic representations still retain cultural specificity. The all-purpose term visual culture can flatten the differences between what pixacão on buildings in São Paulo signifies versus the constant overlay of work on a single, ever-changing wall in Central Square. Street art inherently demands a comparative perspective.

The second is the unfixed, non-predetermined, and non-universalist meanings attached to that activity. Your predispositions are unmoored in a serious way. To give an example of what I mean: when street art in Tehran was taken up as a topic here before, it was in a personal/familial (even anguished) way: graffiti deployed in opposition (and later, punishment) rather than beautification. My uncle's prison sentence after spraying anti-IRI graffiti as a teenager was an entryway to thinking about the openly ideological nature of drawing on walls, which is different than the Euro-American notion of that activity as mere vandalism or destruction.

Maybe there is a third draw. I was born and raised (for more than a quarter of my life) in Tehran. I have yet to write at length about the experience of growing up under the shower of bombings and air raids during the Iran-Iraq War and the collective underground shelters that housed some of my earliest memories. Perhaps someday I will, but the significance is greater than the sum of one person's memory. Tehran is a city (in no particular order) of gray concrete slabs, extreme pollution, class inequity, gender segregation, gridlocked traffic, perpetual car horns, and other unsparing ills. Despite the power that urbanization holds over every district and neighborhood it can be a surprisingly tender and merciful city. It weathers crisis well. Its visual registers are proof of this. (For an important, condensed discussion of the history of urban art in Iran see Shahrzad Ghadjar and Rustin Zarkar's 'Taking Back the Streets: Iranian Graffiti Artists Negotiating Public Space.')

Recently, a friend sent a series of images of public art that reminded me of its terrifically complicated status. Some of the work was commissioned by the government but much of it consists of unaffiliated and autonomous expression. The decisions each muralist took in his or her piece bear thinking about in those contexts.

There is a more urgent need brought to bear on the task of looking at these images (especially outside of Iran), however. It is what every news feed item and broadcast want you to forget about the life and activity teeming there. Euro-America largely knows Iran through the prism of repression, embargoes, war, isolation. No surprise in that. The reelected American President, wasting no time, made his first foreign policy act the enacting of even more sanctions against quite possibly the most sanctioned country in history. (How uncanny that the embargoes cite concerns about internet suppression and other forms of public expression when U.S. sanctions are responsible for a serious shortage in baby formula—Iranian children must bear the brunt of hegemonic interests under the cover of selective 'human rights' criteria about free speech.)

The material these artists use—paint, tiles, metal scraps, spray paint, and acrylics—can never take the place of embargoed baby formula. They are not yet on the U.S.' banned items list (after all, Iran is not yet Gaza). But they are being put to use with impressive variability and imagination.

With thanks to Alireza Doostdar, whose images are used with permission.

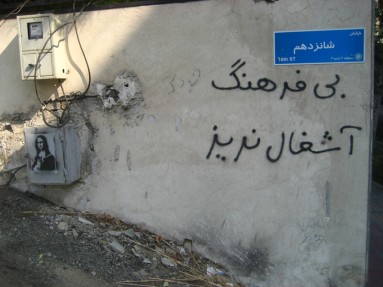

Near Vanak Circle, this writing on the wall reads, 'Culture-less one: don't throw trash.' It appears to be a modern variation on a traditional caution, 'Damn the father and mother of whoever throws trash in this place' «???? ?? ??? ? ???? ??? ?? ?? ??? ???? ????? ?????».

Near Vanak Circle, this writing on the wall reads, 'Culture-less one: don't throw trash.' It appears to be a modern variation on a traditional caution, 'Damn the father and mother of whoever throws trash in this place' «???? ?? ??? ? ???? ??? ?? ?? ??? ???? ????? ?????».

The Mona Lisa's raised middle finger is inscrutable. Is it raised at potential litterers? The anti-litterers who painted her? The world at large? Or perhaps the U.S. Treasury Department?

The Mona Lisa's raised middle finger is inscrutable. Is it raised at potential litterers? The anti-litterers who painted her? The world at large? Or perhaps the U.S. Treasury Department?

Paint is not the only material used. Artists use colorful tiles in intricate geometric patters along walls, often incorporating the design within naturally occurring rock structures.

Paint is not the only material used. Artists use colorful tiles in intricate geometric patters along walls, often incorporating the design within naturally occurring rock structures.

From mid-sized neighborhood parks to large-scale walkthroughs, parks are prevalent in Tehran. People of every stripe take advantage of them, sometimes on a daily basis. The parenting motif in this mural notably depicts two men caring for young children (even though they appear to be walking toward, well, nowhere).

From mid-sized neighborhood parks to large-scale walkthroughs, parks are prevalent in Tehran. People of every stripe take advantage of them, sometimes on a daily basis. The parenting motif in this mural notably depicts two men caring for young children (even though they appear to be walking toward, well, nowhere).

In the background to this miniature-style mural, the Prophet Mohammad rides Buraq to the heavens. In the foreground, an advertisement for pickled olives.

In the background to this miniature-style mural, the Prophet Mohammad rides Buraq to the heavens. In the foreground, an advertisement for pickled olives.

The muralists removed the Prophet's facial features, which were included in the original Mi'rajnama or Book of Ascension (1436-7 C.E.) that the artists copied.

The muralists removed the Prophet's facial features, which were included in the original Mi'rajnama or Book of Ascension (1436-7 C.E.) that the artists copied.

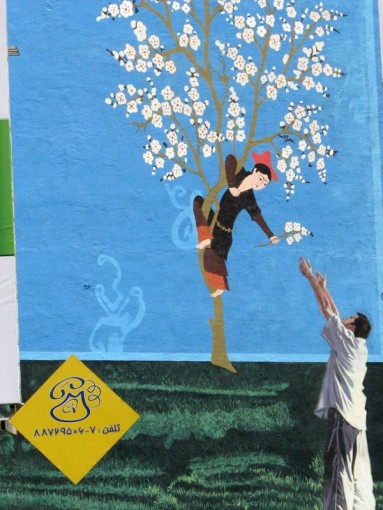

A man painted in the same miniature style extends a bouquet of blossoms to a contemporary man painted in a realist style.

A man painted in the same miniature style extends a bouquet of blossoms to a contemporary man painted in a realist style.

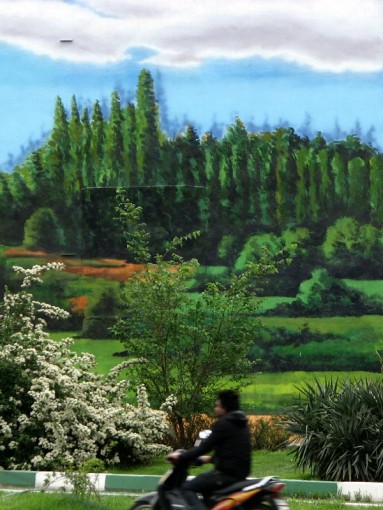

Planted and painted shrubbery share the same palette in a three-dimensional trompe-l'œil.

Planted and painted shrubbery share the same palette in a three-dimensional trompe-l'œil.

Even the refuse space of a highway underpass—usually considered a 'non-place'—is beautified.

Even the refuse space of a highway underpass—usually considered a 'non-place'—is beautified.

This woman's appearance, colorful and touched by traditional peasant patterns, contrasts with the drab that surrounds her. Also notable is the decision to extend a private indoor space to the outside world.

This woman's appearance, colorful and touched by traditional peasant patterns, contrasts with the drab that surrounds her. Also notable is the decision to extend a private indoor space to the outside world.