The tension between experience for its own sake and experience we pursue just to put on Facebook is reaching its breaking point. That breaking point is called Snapchat.

It is a nostalgic time right now, and photographs actively promote nostalgia. Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art. Most subjects photographed are, just by virtue of being photographed, touched with pathos. An ugly or grotesque subject may be moving because it has been dignified by the attention of the photographer. A beautiful subject can be the object of rueful feelings, because it has aged or decayed or no longer exists. All photographs are momento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.

—Susan Sontag, from On Photography (1973)

A photograph is made of time as much as it is of light — a frozen shutter-speed-size gap of the present captured within a photo border. Despite this, photographs have always been a way to cheat death, or at least to declare the illusion of immortality through lasting visual evidence. There’s always the possibility that the next photo you take will one day be lovingly removed from a box by some unborn great-grandchild; the Polaroid developing in your hands might come to be pinned to someone’s bedpost in posterity. To update that to more contemporary terms, your selfie on Instagram might be a signpost for the future you of what it was like to be this young.

On Snapchat, images have no such future. Fittingly, its logo is a ghost.

By refuting the assumption of the permanence of the image, Snapchat is a radical departure. It inaugurates temporary photography, in which photos are seen once by their chosen audience and then are gone in 10 seconds or less.

The temporary photograph’s abbreviated lifespan changes how it is made and seen, and what it comes to mean. Snaps could be likened to other temporary art such as ice sculptures or decay art (e.g., Yoko Ono’s famous rotting apple) that takes seriously the process of disappearance, or the One Hour Photo project from 2010 that has as its premise to “project a photograph for one hour, then ensure that it will never be seen again.”

To understand the emergence of temporary photography, one must understand it in relation to the inflating archive of persistent images and their significance on how we perceive and remember the world.

The logic of the camera is that reality is real only to the extent that it is photographable. It pulls individuals out of the moment and makes them see it (and themselves) as an object for the future as well as always already of the past. This seizing of experience's ephemerality — to possess the present, docile and durable — is what Andreas Kitzmann called a “museal gesture,” what Jean Baudrillard called “museumification,” and what André Bazin called the “mummy complex,” the “need to have the last word in the argument with death by means of the form that endures.” It’s ownership of the present by proxy.

As Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography,

there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.

Sontag notes that this makes for a nostalgic gaze, an understanding of the world as primarily documentable. For those who live with status updates, check-ins, likes, retweets, and ubiquitous photography, such an understanding is near inescapable. Social media have invited users to adopt a sort of documentary vision, through which the present is always apprehended as a potential past. This is most triumphantly exemplified by Instagram’s faux-vintage filters.

There’s always tension between experience-for-itself and experience-for-documentation, but social media have brought that strain to its breaking point. Temporary photography is in part a response to social-media users’ feeling saddled with the distraction of documentary vision. It rejects the burden of creating durable proof that you are here and you did that. And because temporary photographs are not made to be collected or archived, they are elusive, resisting other museal gestures of systemization and taxonomization, the modern impulse to classify life according to rubrics. By leaving the present where you found it, temporary photographs feel more like life and less like its collection.

The photograph, for all its promised immortality, always hinted at death. This was central to Roland Barthes's analysis in Camera Lucida, that the enduring image “produces Death while trying to preserve life.” Documenting the present as a future past, as conventional photographs do, asserts the facts of change, impermanence, and mortality. The temporary photograph does the opposite: It interrupts the traditional photographic fixation of the present as impending history by positing a present moment that’s not concerned with the past or the future. As such, the temporary photograph is necessarily less sentimental and nostalgic. By being quick, the temporary photograph is a tiny protest against time.

***

Let’s face it, much of photography was already becoming Snapchat even before Snapchat existed. While much is justifiably, if hyperbolically

, made of “the death of privacy” in the age of information immortality, the likely fate of the vast majority of images today is to be briefly consumed and quickly forgotten. As well as offering relief from deepening documentary vision, the temporary photograph also responds to this photographic abundance, which has deflated the value of images. As making more and more photos becomes easier, each individual shot means less and less. Snapchat is an attempt at re-inflation.In their scarcity, photographs can age like wine, with grace and importance. In their abundance, photos can sometimes curdle, spoil, and rot. But from the beginning, technological innovation in photography has driven toward creating visual abundance. Daguerre is widely credited as inventing photography, in 1839, in part because earlier mechanical image-capturing techniques — most famously Niepce’s so-called heliography — did not create as many images as quickly and reliably. In subsequent decades, major advances shortened exposure times and made images even more easily reproducible, chiefly through replacing photographic plates with paper. Photography democratized dramatically with the introduction of Kodak’s small, cheap, and easy-to-use personal cameras at the turn of the 20th century. The ads proclaimed, "You press the button, we do the rest." And then there is the rise of digital photography and smartphone cameras that make taking, duplicating, and viewing photos something many people do almost anytime and anywhere.

As photographic technology expanded photography's user base, the photograph went from a rare prized possession to common keepsake to a nuisance that clutters our visual memories. Writing of this visual oversaturation, Michael Sacasas worries that

digital photography and sites like Facebook have brought us to an age of memory abundance. The paradoxical consequence of this development will be the progressive devaluing of such memories and severing of the past’s hold on the present. Gigabytes and terabytes of digital memories will not make us care more about those memories, they will make us care less.

By simulating the aesthetic of photographic scarcity, Instagram works as a response to (or overcompensation for) this fear — the enchanting landscape, disarming portrait, the bold statements and delicate textures look like moments captured from the past for posterity. These are the visual cues of photography pre-digital-devaluation, right down to the warm colors, faded glow, and false paper scratches and borders. Instagram’s faux-vintage filters, as I argued previously, reassure that present lives are just as authentic and worthy of nostalgia as the life captured in the seemingly scarce images from the analog past. Photographs are becoming too easy, so, dammit, here’s my life framed like it’s 1942.

But having an Instagram account is like having an abundance of money in a dead currency. So much nostalgia and meaning have been shoveled at us that the aesthetic has lost much of its ability to affect. Merely making your photos evocative of photo scarcity doesn’t make them actually scarce or make others covet them. There’s a deep mismatch between the aesthetic language of Instagram and the affordances of the network. Despite all the manufactured nostalgia, your photo disappears down the stream, largely unnoticed.

So whereas Instagram merely evokes the look of scarcity, temporary photography by definition enforces a certain rarity that imbues the image with a heightened aura of meaningfulness. Snapchat inspires memory because it welcomes the possibility of forgetting. Instead of being shared with a large number of people on a popular website, temporary photographs are taken specifically for and shared with one other person or a small group of people. The meaning of the photo doesn’t rest just in its content but in the choice to restrict its consumption — the choice to send that particular image to that particular person at that particular time, to the exclusion of other images, other recipients, and other times.

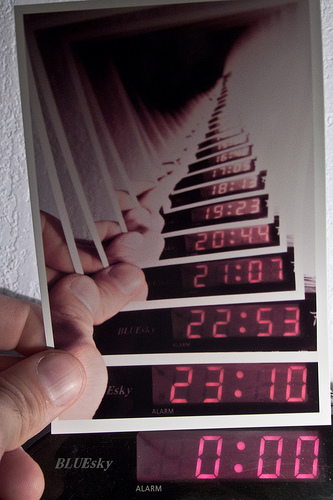

The ephemerality sharpens viewers’ focus: Once received, a Snapchat count-down is a kind of time-bomb that demands an urgency of vision, a challenge to exhaust the meaning from the image before the clock runs out. Unlike a paper photo that fades slowly over the years, the temporary photo disappears suddenly. Given only a peek, you look hard.

The temporary photo will wrongly be called frivolous or trivial — after all, only unimportant images could be so easily parted with. But as we have seen, there is meaning in witnessing ephemerality itself, an appreciation of impermanence for its own sake. By carving a space away from the growing necessity to record and collect life into database museums, temporary photography encourages an appreciation of the importance of experiencing the present for its own sake.

We might be witnessing an extraordinarily rare, even if minor, countertrend to photography’s increasing abundance — a sort of photographic population control. In this way, the rise of self-deleting photographs might be as much about reinstating the importance of nontemporary photos as it is the enactment of photographic disposability.

If everyday photography becomes temporary photography — if more people switch to apps like Snapchat and Poke — photos saved to more permanent locations like Facebook will become correspondingly more scarce and perhaps seem more important. Photographs taken and shared as temporary will impart more meaning to those chosen to be permanent. In the age of digital abundance, photography desperately needs this introduction of intentional and assured mortality, so that some photos can become immortal again.

Comments are closed.