An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

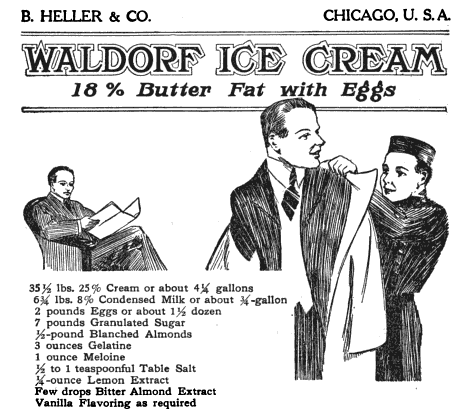

Images from Heller's Guide for Ice-cream Makers (1918)

The scoop on how a familiar frozen treat once got respectable folk all hot under the collar

Summer has arrived in Maine and I've dug out my ice cream maker.

This ice cream maker was a gift. And like many gifts, it's also somewhat of a curse. It coaxes me into making ice cream every two or three days. This means I must also eat a pint of ice cream every two or three days. I try to make my ice cream healthier than usual, using stevia instead of sugar and coconut milk instead of cream. Still, it feels like an almost criminal indulgence.

"Self-indulgence produces a vanity of all vanities" --Unknown

I'm certainly not alone in feeling this. "Ice cream is exquisite," observed Voltaire. "What a pity it isn't illegal."

For most of history it may as well have been illegal. Only the richest could afford to eat it regularly. The Roman emperor Nero was a fan, wine and honey his favorite flavor. Before him was Alexander the Great, who had his slaves dig great pits and fill them with snow so that he might always have his favorite treat.

Ingredients and tastes varied. Chinese emperors of the Tang Dynasty liked their ice cream a special way: Fermented buffalo or goat milk was heated, then thickened with flour and seasoned with camphor, which made it flake like snow. For good measure fragments of reptile brain were added, along with an eyeball or two.

In Japan the 4th century emperor Nintoku was so taken with ice and its ability to preserve food that he declared June 1 to be national ice day.

You have to look to the Middle East to find an early instance of ice cream that doesn't involve lizard brain–freeze. On torrid afternoons Arabs would drink an iced refreshment they called

shabat or

sharab. Called by us "sherbert," it was made from pomegranates, grapes, cherries, and other fruits. Its taste inspired one English novelist to muse that it was "so mixed that the sour and sweet were as equally balanced as the blessings and miseries of life."

Antonio Latini, an overseer of kitchen and food operations for a Spanish viceroy in Naples, is thought to be the first person to write down recipes for making and serving sorbetto.

Making ice cream was an exhausting ordeal, mostly because it involved chopping lots of ice. People took every opportunity to avoid it. In 1758, Francis Fauquier, lieutenant governor of Virginia colony, used ice from a hail storm to make his ice cream.

Adventurers took the recipe for sherbert back to Europe. The lords and ladies thereof came to relish it, inventing recipes of their own, adding wine, spices, and more familiar fruits like raspberries and peaches. Invention took its course, and soon these slushy, fruity drinks grew more substantial. And though the ingredients didn't much change -- they still consisted of ice, fruit, sugar -- the name did. Thicker, heartier, sherbert became

sorbetto.

The birth of sorbetto saw inventiveness take off, especially in Italy. One enterprising Italian decided to experiment by adding cream. The result was a vastly more luxurious product: a frozen custard. Custard itself was nothing new; since antiquity people had made it from such various ingredients as almonds and cream. But no one had thought to freeze it.

Cooks could be very inventive when making ice cream. Sometimes they added saffron to impart a golden hue, and sometimes citron and rosewater. One even fashioned a "cabbage cream" by building up skins of custard "round and high like a cabbage." Others whipped them to create "snows," and flavored them with orange water.

In 1774 a Scottish colonist by the name of William Black wrote an early description of this iced custard. Black was secretary to a commission appointed by the governor of Virginia to work with delegates from the Pennsylvania and Maryland colonies. This meant he was invited to a lot of fancy dinners, one of which featured "a Table in the most Splendent manner set out with a Great Variety of Dishes no less Curious; Among the Rarities of which it was Composed, was some fine Ice Cream which, with the Strawberries and Milk, eat most Deliciously."

Some of Black's fellow diners had a different opinion. They worried that eating ice cream would eat them away, suspecting that the saltpeter used in making it could get into the pot, into the liquid, and into them. Others feared the effect of eating too many cold things could disrupt the body's normal functioning. When visiting Florence

King James I had two brick-lined snow pits dug in the ground at Greenwich between 1619 and 1622.

, where ice cream appeared on seemingly every menu, Montaigne said that though it is "customary here to put snow into the wine glasses" he made it a practice to "put only a little in not being too well in body."

Still, the taste for ice cream spread far and wide. In 1686 a Sicilian, Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, opened a café where Europe's great political and intellectual luminaries gathered. Napoleon, Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Balzac, and Benjamin Franklin among others ate ices of various kinds there.

As the centuries passed, eating ice cream became less a matter of privilege and more a matter of pocket money. This was most apparent in the big industrial cities of Britain and the United States. There, in the 1850s, in towns and cities such as, London, Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and New York, Italians introduced ice cream to the working classes. These itinerant vendors of frozen custard awoke each morning before dawn to crank and freeze the custard, before setting off with the small painted wooden carts from which they sold it. At their cry of "Gelati, ecco un poco!" crowds formed. "[T]he street gamins and errand boys buzz around their barrows like flies about a sugar barrel," wrote London chronicler Andrew W. Tuer in his 1897 publication Cries.

"For your class, the best diet is one that is substantial and simple. Your breakfast should be composed of oat-meal porridge and milk, or bread and milk. For dinner, animal food; either butcher-meat or fresh fish should be taken every day, along with one or more of the more wholesome vegetables, as potato, turnip, and carrot. After returning home from labour, a draught of tea or coffee will be pleasant, and will afford more wholesome refreshment than ardent spirits, which are then frequently used; and, it it is found to agree, a little nourishing food, such as an egg, or even a little butcher meat, should be taken some time before retiring to rest." --From Address to the Working Classes on the Prevalence of Fever, and Disease in General (1838)

Most of these vendors made a pittance. A successful few made enough to open ice cream parlors every bit as richly appointed as their counterparts in Italy. With mirrored walls and leather seats, these parlors became the scourge of the prudish bourgeoisie, who saw them as papist dens of vice. In May 1906 the

Glasgow Herald carried a report of a memorial for the British Woman's Temperance Association under the headline "An Objectionable Trade." The Association argued that ice creams shops had become one of the "most objectionable and pernicious aspects of Sunday trading in Scotland" and had reached "alarming numbers."

A few days after the memorial's publication, a Joint Parliamentary Committee on Sunday Trading convened, during which the Chairman of the Scottish Shopkeepers and Assistants Union was cross-examined.

"Do you urge immorality against these ice-cream shops?" he was asked.

"I should not like to urge it, but it is known," came the answer.

Among the more egregious crimes committed by the shops' proprietors was that of allowing young people of both sexes to intermingle and smoke. One inspector had said that he had seen girls of "tender years" smoking cigarettes in the shop. They were also seen dancing to "music supplied by a mouth organ." Even worse, some of these young girls had become prostitutes.

Another inspector was asked: "Do you ask us to believe that the downfall of these women was due to ice cream shops?"

"I believe it is," he replied.

It was concluded that ice cream shops embodied "perfect iniquities of hell itself and ten times worse than any of the evils of the public house. They were sapping the morals of the youth of Scotland."

Recipe for Nesselrode, or Frozen Pudding from The Ice Book: A History of Everything Connected with Ice, with Recipes (1844): "Take one pint of cream, half a pint of milk, the yolks of four eggs, one ounce of sweet almonds pounded, and half a pound of sugar; put them in a stewpan on a gentle fire, set it as thin as custard; when cold, add two wine-glasses of brandy and two wine-glasses of nectar, (a delicious beverage, prepared only by the author.) Freeze, and when sufficiently congealed, add one pound of preserved fruits, with a few currants; cut the fruit small, and mix well with the ice, and put it into moulds, and immerse them in a freezing mixture, such as ice and salt, &c., until required for table."

Whether ice cream did indeed sap morals was never adequately demonstrated. But the threat of the lower orders enjoying themselves too much was enough. We still wring our hands when we think the underprivileged are overindulging. Meanwhile, there's talk these days of how sound nutrition and other rational choices may only be made by those whose cognitive energies aren't used up by the daily crises of an uncertain economic outlook. Wealth, in other words, offers certain guarantees. For the rest of us, it's just a lick and a promise.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.