The riots provided a long-sought opportunity for settling scores; rioters spoke of 'payback.'

- Investigative report on the 2011 London Riots conducted by the Guardian and The London School of Economics

Sometimes it's important to start with numbers. When it comes to inter-generational conflict, tied as it is to stories about Oedipus and Hamlet, numbers help ensure we're speaking of a particular relation rather than a mythic archetype.

These are some numbers:

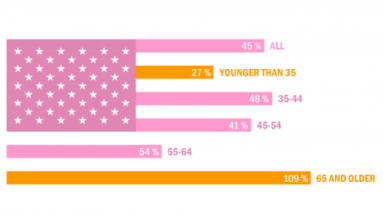

A 2010 Congressional report put youth unemployment at 20 percent, “the highest rate ever recorded for this age group.” The same report noted that young workers are severely overrepresented among the unemployed, making up 13 percent of the labor forced and 26 percent of those out of work.

Between 30 and 40 percent of Americans will be arrested before they turn 23, a significant increase from the 1965 rate of 22 percent. This despite a large drop in victimizing crime generally, and victimizing crimes attributed to young people in particular, over the same period.

Among those surveyed who could name an age group hit hardest by today's economy, 45 percent said “young adults” rather middle-aged or older. In 2011, for the first time since Gallup started asking respondents the question in 1983, less than half of Americans said they believe the next generation will be better off than they have been.

Since 1978, tuition at US colleges has increased 650 points above inflation dwarfing the rates of increase for housing and healthcare over the same period and leading to over $1 trillion in student debt held disproportionately by the young.

This is an actually existing generational war, and it's not over the aesthetics of hair length, uptight social conventions, or even the dream of economic mobility. For young people, it's a tooth-and-nail scrap for survival in a world system they recognize as not simply cold, but antagonistic and draining.

-

When Roosevelt Institute economics expert Mike Konczal digitally parsed the information from Occupy Wall Street's “We Are the 99%” Tumblr, on which participants and sympathizers explain the personal circumstances surrounding their involvement, he found a heavily skewed age distribution: the 1000 or so posters had a mean age of 29 and a median age of 26. This distribution is especially striking considering there are only two submitters under the age of 12. Among their central complaints were debt (specifically student debt) and employment, but their concerns were tied to the basic reproduction of their lives more than to the achievement of any status or material goods. The word “body” appears more in the set of terms than “house,” “home,” or “car.” Konczal doesn't see in these laments the desire for a classic American “good life,” but something older:

They aren’t talking the language of mid-20th century liberalism, where everyone puts on blindfolds and cuts slices of pie to share. The 99% looks too beaten down to demand anything as grand as 'fairness' in their distribution of the economy. There’s no calls for some sort of post-industrial personal fulfillment in their labor — very few even invoke the idea that a job should 'mean something.' It’s straight out of antiquity — free us from the bondage of our debts and give us a basic ability to survive.

When Konczal writes of the “99%” he doesn't mean the literal aggregate, but the people who have chosen to identify with the collectivity, a group with a very uneven age distribution. This isn't because the young are American society's most oppressed, but because a confluence of factors beyond being made miserable (including but not limited to: extremely low rates of unionization, a common proficiency with electronic communications technologies, a tenuous relationship to the job market, culturally imbued entrepreneurial aspirations, and a sophisticated spectacle industry selling them anarchy) provide the conditions for the occupations' decentered organization. None of these factors is a particularly progressive sign, but together they determine new sensible lines of resistance, new stories about how people can change what it is they see and feel around them every day.

![]()

![]()

Class politics have become intelligible as a generational politics, the forces of what is and what has been arrayed against what else could be. For some the divide is the result of a promise betrayed, whether that promise was that they could maintain their inherited class positions or improve them. For others it's a recognition that existing institutions are so riddled with predation and corruption, or tied inextricably to ecological devastation, that even their maintenance is unthinkable work. For still others it's the trauma of service in the latest set of American wars, always declared by the old and fought by the young, or the accumulation of years of police harassment. Some occupiers hardly know why they're there. If there's one thing the 99% rhetoric got right it's the 1% thing; there's a serious conflict not between the percentages (such an uneven fight would already be over), but between the two sets of associations. This is politics: a vision of division, a line of conflict.

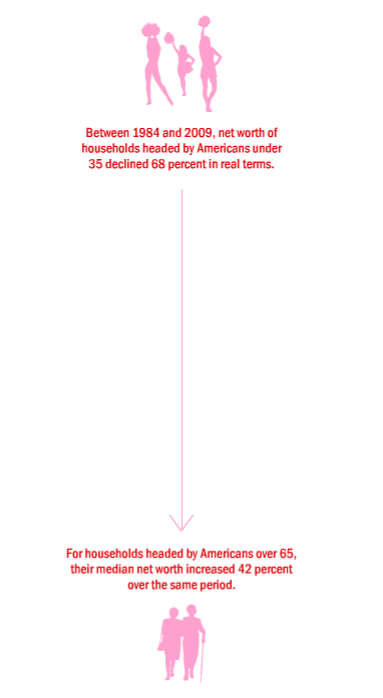

As the statistics have demonstrated, young Americans don't just imagine themselves as beaten down: 37 percent of households headed by someone under 35 have less than zero dollars in net worth. And this metric heavily underestimates young Americans' desperation by excluding those still counted as dependents.

But how could this be the case? If such a high percentage of young Americans were literally destitute, there would be homeless encampments in every major city in the country.

Leaving aside the fact that there were homeless encampments in every major city in the country before police violently intervened, the household poverty numbers from Pew reveal the extent to which debt distorts young people's economic picture. Since a person's net worth includes both total assets and debt, high rates of student loans and low rates of home-ownership push a large proportion of young Americans into the red. Whereas other measures treat debt as unreal, in net worth it's the rest of a household's assets that aren't really there when the collectors come calling. The measure treats every household as if repo men had just come and settled their outstanding loans. The numbers mean that at least 37 percent of young families couldn't cover their debts with all their possessions combined. Of the young people living with their parents who go uncounted in the household numbers, over 45 percent are in poverty when measured as individuals. No matter how you slice the numbers, the central dilemma is hard to avoid: A dangerous portion of young Americans owe more than they reasonably expect themselves to be worth in the future.

It isn't a stretch to call the recent wave of American occupations a youth movement. Originating from student struggles against high tuition — in California, New York, and most militantly, Puerto Rico — the occupations channeled young Americans' fear and insecurity into often inchoate action. The desire for a chance to live with one's head above water doesn't translate neatly into policy offerings. Massive debt relief could make a dramatic difference, but it's hard to imagine a policy that would be less popular in America than forgiving $1 trillion in student debt on the grounds that it was totally unreasonable to charge students so much in the first place. Sitcom audiences laugh at every “arm-and-a-leg” tuition joke.

Perhaps this sense that debt has reached absurd and unimaginable proportions is why Occupy Wall Street cleared 50 percent approval in national polls. This despite being largely composed of a bunch of groups (anarchists, communists, socialists, homeless people, punks, college kids, hippies, conspiracy theorists, drummers) that are much less popular when disaggregated: the resonant slogan “shit is fucked up and bullshit” makes sense to a lot of people, not least of all because it doesn't suggest any kind of obvious answer. By now it's clear that the purpose of the camps and marches wasn't to convince someone in charge to fix something. The debate about whether or not to issue demands to those currently in power was settled in California and New York, before Zuccotti Park was occupied, where insurrectionary left-communists set the agenda. In “Communique from An Absent Future,” a pamphlet out of the California student occupations that helped popularize the tactic, the group of anonymous authors wrote:

As the unions and student and faculty groups push their various 'issues,' we must increase the tension until it is clear that we want something else entirely. We must constantly expose the incoherence of demands for democratization and transparency. What good is it to have the right to see how intolerable things are, or to elect those who will screw us over?

It's this language that found purchase nationally, despite (and no one should be confused, it is despite) finding its direct antecedents in fringe radical theory. No matter what the pseudo-official pronouncements out of the occupations say, the encampments haven't been about prefiguring a better society. Few occupiers are so naïve as to really think a ramshackle group of tents in a corporate non-park in the middle of New York City's financial district could or should function like a post-capitalist biodome. Occupation is one kind of action a group with no self-perceived leverage takes. It's a tactic based on a tension at the very root of governmental power: Bodies take up space, and if those limbs are determined not to move, it takes force to move them.

The sort of hopeless debt sketched out earlier reduces its holders to bodies stripped of assets, including the agency that is supposed to come with being a free laborer. For a sizable portion, these bodies don't even own their own bodies insofar as the products of their future work are already promised.

Massive debt spread widely over the cohort makes its individual payment increasingly more difficult, which, due to interest, increases the size of the collective total owed. Because young workers perform under virtual indenture, their labor is less valuable on the market. High unemployment, along with the debt, renders them always vulnerable to replacement by an equally educated, equally hopeless peer. It's only one of the harmful self-perpetuating cycles into which the economy has thrust young workers. As for the potential benefits collective bargaining, four times as many American workers under 24 are officially unemployed as belong to trade unions, and that ratio is not likely to improve.

President Obama sold himself so successfully to young Americans by mirroring our hopes for post-Bush reform that the resulting disappointment is directed more toward the hope itself than the man who never stood much of a chance of fulfilling it. It's in this situation, when reform in the government and in the workplace feels exhausted, that the framework of liberal aspirations and demands collapses. And Occupy Wall Street is the most palatable instantiation of this post-hope politics by process of elimination that we're likely to see.

-

Bodies take up space, and young bodies don't own much of their own. Fiscal austerity, whether it's in New York or Madrid, involves tightening racist and ephebiphobic restrictions on public spaces. When the police fire shots across the generation gap, it's often in the course of managing this territory.

Zyed Benna, 17, and Bouna Traoré, 15, electrocuted fleeing police in the Paris suburbs. The teens had been playing soccer at a public park after closing hours and were afraid of being interrogated by police.

Alexandros Grigoropoulos, 15, shot and killed on an Athens street by Greek Special Guards, the police division responsible for patrolling public spaces.

Oscar Grant, 19, executed face-down on the ground of an Oakland train station, his arms behind his back, a transit officer astride his legs.

All of these deaths provoked significant civil disturbances, and the fires still smolder and flare in Athens and Oakland. But these aren't 20th century style race riots. These days when disorder runs rampant, it's the young doing the running. Sometimes we see these eruptions partially compartmentalized by different identifications, as in France when the crippling protests by young workers followed the unrest in the largely immigrant Paris banlieues by four

months in 2005-06, or in the UK where aggressive anti-tuition actions preceded the Tottenham riots by eight months in 2010-11. At the Oakland occupation, where the critique has placed a major emphasis on racialized police violence, the lines have blurred.

The international business press has been quick to connect the dots and note both the rise in inter-generational tension and the risk of civil unrest. In February 2011, well before the riots rocked London, Bloomberg Businessweek ran a major article comparing UK youth unemployment to the rates in pre-revolutionary Tunisia and Egypt. The cover reads “THE KIDS AREN'T ALRIGHT” in block caps, superimposed over a young man hurling a brick.

It isn't worth the breath to ask whether anyone should advocate riots, how politically conscious they are, or whether the generational lens obscures class divisions. The die — or better yet, the mold — is already cast. As the writer Evan Calder Williams put it in his “open letter to those who condemn looting” after the riots in London:

One doesn't defend a riot. It is not 'good' or 'bad.' A riot is a scrambling of positions of belonging and of judgment. Often, it is an internal dissolution of what might have appeared common lines of class.

It involves situations the likes of which we are sure to see more, the turning of the hopelessly poor against the poor-but-just-getting-by, between shop-owners and looters, between workers and rioters, between those breaking the windows and those who clean them, and, internally, between individuals themselves, who cannot always be split into one or the other.

Violence isn't an answer; it's the question's premise. Debt and austerity don't just happen, they must be imposed upon a population, and one of Occupy's greatest contributions has been to reveal the kind of instruments the state expects to use. As the California student movement puts in: “behind every fee increase, a line of riot cops.” Across age demographics, Americans expect the worsening that has already begun. There have been casualties, and the body count will only rise.

Like the miller's daughter in the fairytale, assetless student debtors had to spin gold out of straw – gold that's somehow always already owed to someone else. All the Rumpelstiltskin market asked in return for pulling this amazing sum out of thin air was nine months of her labor, slaughtered, weighed, and priced to sell before it's ever performed. Not even the living labor of indenture, but value stillborn, birthed cold.

But a global economy can only rest on straw for so long. Capitalism, and any other system premised on unending growth, will always produce inter-generational tensions, for each further set of workers must be more productive than the last. The conflict between succeeding modes of production emerges as a generational clash.

Today's young people will be the ones to adapt to this new normal and stabilize it, or to reject it in a stumbling search for something else. We should understand the demand for the “basic ability to survive” counterposed not just against literal death, but also the social death of life-on-loan. The possibility of falling short is implicit in the demand, but is there anything more dangerous than a mob wielding bodies they don't own, swinging for their lives with rented arms?

If this generational debt will be enforced by armed guards—and it will—then it will be paid, one way or another, in blood. Exactly whose, it is too soon to tell.