Randall Halle: Now of course you recently finished a film precisely on the conditions in Eastern Europe. The first section of your film Videogramme of a Revolution utilized images of the Romanian revolution captured on video by nonprofessionals. The commentator of the film draws our attention to the style and position of the camera. These cameras seem to mark the beginning of the breakdown of a system of censorship. In your estimation do they signify openings or do they actually create a free flow of information?

Harun Farocki: A film linguist–in case that exists or should ever exist–should make a comparison of the TV during the Ceausescu era with the revolutionary TV of Studio 4. During the Ceausescu period, just like in the courtly theater, there were minutely determined positions for the ruler and all camera operations were used to reinforce the established order. Also the next in rank had a position and the main purpose of TV was to present this image of hierarchy again and again. Along those lines–I recall that the major network news programs in the US also have an established idiom and also a fixed camera rhetoric, whenever the anchor person turns it over to the reporter on the scene, and when they take it back again. Is this also about reinforcing authority in the presentation of the news?

In those days when the TV stations were in a state of emergency, Studio 4 presented a multifold and multifaceted lack of order. There were way too many people in the small studio and very often a man would speak–very few of them were women–who was barely visible or not visible at all. In contrast to the emptiness of images in Ceausescu's TV, which was rather an aesthetics of the poverty of mind, certainly not minimalism, there was suddenly a superabundance and the hierarchies were uncertain.

In only a few days the Romanian television underwent a great leap forward from a monarchial television in the spirit of pre-1914 to a postindustrial style. We know that in almost the entire world the consumer today does not wear work clothes but casual clothes; as if everyone was just coming from hobby work in their garage or from a big shopping trip. Television also tries to acquire this habitus and one witnesses that effort in its process of appropriating the new.

There is even more to be read out of this. In the beginning the revolutionaries were acting like citizens, and after a short time the same people keep appearing and offering themselves as politicians. We find something similar in the camera movement: during the first hours the images are of an operative nature and then shortly thereafter the cameras begin to offer possibilities for a new television, for all the coming jobs in media. Our film shows a scene with about twenty people who have simply pointed the camera and microphone at a television that was reporting about the trial of the Ceausescus and their execution. One and a half years later, when we were back in Bucharest, one of the cameramen who was in this room at that time had already received a license for a private TV station. He already owned his own horses.

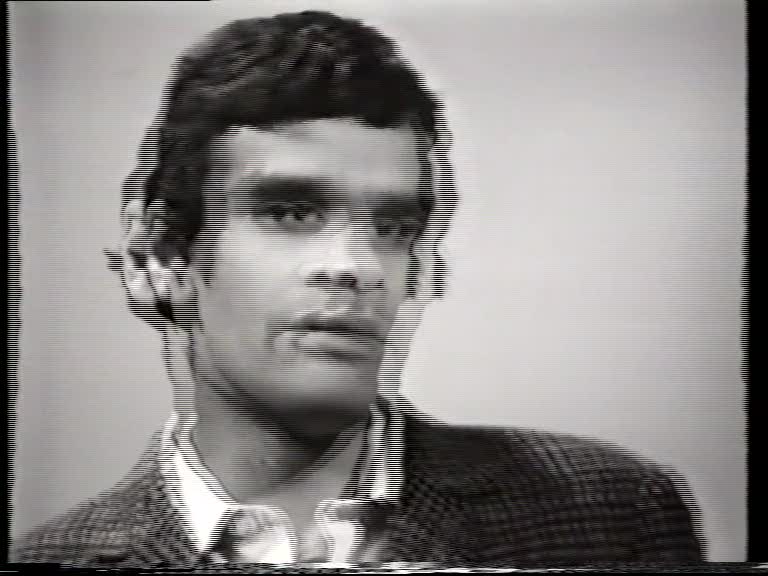

Harun Farocki (1944-2014) passed away last week. PDF of this interview here.