Lynda Benglis’s portrait of herself scandalized not because it supplanted the phallus but because it ridiculed it.

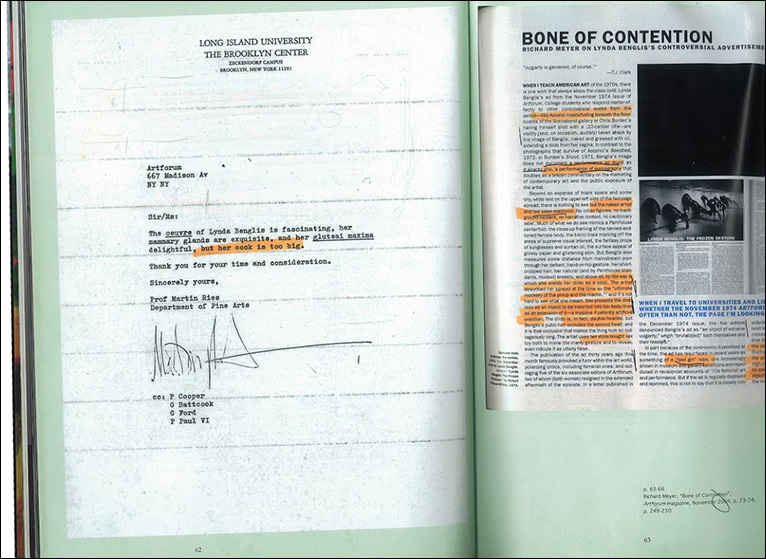

In the December 1974 issue of Artforum, five editors published and co-signed a letter “publically disassociating” themselves from portions of the previous issue. The letter cites the “extreme vulgarity” and “brutalizing” effect of an advertisement placed in the November 1974 issue by and for a New York artist, a sculptor, appearing as herself in the image. The editors condemn the uncouthness of the ad as a harmful mockery not only of the editors’ personal sensibilities but also of the larger (and conveniently undefined) “aims of [the women’s] movement.” Another grievance: As art writers and editors, these five felt professionally compromised by their forced complicity with the artist’s self-exploitation—or worse, self-promotion, “in the most debased sense of the term.”

Professional feminists agreed, with Cindy Nemster accusing the artist of “making a frantic bid for male attention.” Art historians were scandalized. School principals pulled their schools' Artforum subscriptions. The magazine received more letters for a single issue than it had in its 13-year history. In Philadelphia, a man reportedly stormed into a museum, waving his copy of the issue, and toppled over one of the artist’s works. In a no less extreme reaction, the two women among those five editors—Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson—would soon quit the magazine to start October. Everyone knew their departure had begun with an advertisement.

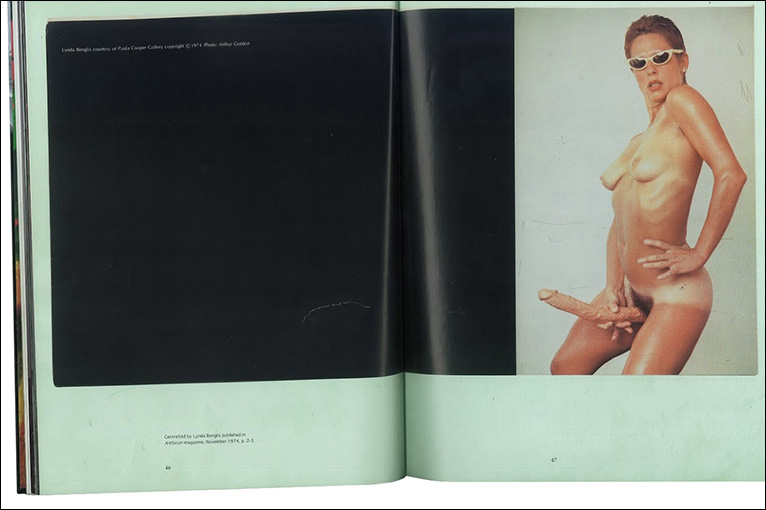

Because all this happened two decades ago, when shock was still a thing, it’s easy to wonder how bad this ad could have been—until you see it. I’ll never forget the first time: halfway through a mid-morning, dreary art history lecture, the whole room of students sitting upright at the projected sight of an extra-long dildo with one end well into the bush of a slim, oiled-up woman striking a hip pose, sunglasses shielding her glare, one hand resting above her panty tan line as the other strokes her veiny, double-headed dick, which reached a foot or two above the professor’s head. A modest credit, running flush left in white font across the mostly black centerfold, spelled out “Lynda Benglis, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery. © 1974.”

Benglis, 33 years old at the time, had studied painting at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, where she developed a Pollockish style of pouring paint over gallery floors. By the 1970s, now fully engaged in sculptural work, she addressed the AbEx’s “frozen gesture” both as sculpture and performance, “to mean something both physical and psychological.” In April 1974 at Paula Cooper Gallery, she presented “Knots,” the solo show reviewed by Robert Pincus-Witten in Artforum which appears several pages after the advertisement in the November ’74 issue.

Benglis had at first suggested her dick pic accompany the review, but Artforum editor John Coplans shut her idea down, saying the magazine did not sell editorial space. If Benglis was to include her dick pic in Artforum, not only would she have to pay double the ad rate ($3,000) to cover potential issues with the printers, but she would also be denied the cover. She took the deal. Meanwhile, the editors chose to illustrate Pincus-Witten’s piece in part with a photograph of Benglis in which she is not well endowed but rather bending over. This portrait, taken by Annie Leibowitz for the Paula Cooper show invitation, depicts Benglis bare-assed from behind, her right arm lifted above her turned head, almost concealing her raised eyebrows, peering back. Far from the full color Benglis, the artist in this young-looking portrait is vulnerable, even a bit coy, her unbuttoned jeans sagging at her ankles, her backward glance purring “come hither” while barely meeting the eye. It seems as if the vulgarity of a particular image rested more comfortably on the magazine’s conscience when the woman in it appeared passive, receptive to editorial hard lines, letting the editors forget that despite their stance on advertising they’d chosen an image intended as a promotional tool.

And this is just the tip of Artforum’s apparent hypocrisy. Earlier that year, Benglis made a bet with her fellow artist, sometimes lover, and frequent collaborator Robert Morris to see which of the two could produce the most virile, self-aggrandizing announcement. First up was Benglis, in the 1974 April issue of Artforum, posing for an announcement of “Knots”—dressed a bit butch but covered up, still slicked, hand on hip, leaning on a car. In the September issue, Morris followed with a poster for his solo show at Castelli-Sonnabend. Seemingly set in a gay BDSM fantasy, the ad had him topless with a full beard, accessorized by a spiked silver choker, metal cuffs, sunglasses, and what Roberta Smith later described in the New York Times as a “Nazi-vintage” military helmet. The kicker: Rosalind Krauss took the picture. At the time, Krauss was living with Morris; perhaps this is what she meant when she wrote in the December 1974 letter that Artforum condoned only specific vulgarities and not others. In an essay commissioned for a 2009 monograph on Benglis, Franck Gautherot encapsulates the insincerity of this statement:

When Benglis was seen on the verge of sticking a dildo up herself, endless debate, censorship, and cursing to the high heavens occurred where Morris had received no banishment for parading in a fascist-like stance and photographed by a titillated Rosalind Krauss. The crude, macho-fascist, Hell’s Angels–style with polished chains and toned pectorals inspires respect … Women’s lib still had its work cut out.

The feminist art historian and critic Amelia Jones rightly holds up the disparity between Morris’s and Benglis’s receptions as even more evidence that the art world has always graded male and female artists on unfairly differing criteria. Yet while the image would certainly have been less intimidating were Benglis a man, gender isn’t the only critique at play. The critic Dave Hickey writes that “contrary to urban myth, male artists have always been welcoming to female artists—except for artists like Lynda Benglis … whose sheer talent and charisma scared the hell out of everybody, women included. In these cases gender insults are never about gender. They’re always about talent and sex.”

Essentially, Benglis wagged her sex as a middle finger to all the macho dicks that overpopulate the art world (and the women [editors] who suck them?). The sculptor didn’t supplant manhood; she ridiculed it. In a letter sent to Artforum in support of Benglis, Arlene Raven and Ruth Iskin from the Center for Feminist Art Historical Studies in Los Angeles blame the editors’ “impassioned protest” toward the image on its “graphically show[ing] a woman achieving machismo—taboo for women, taken for granted in male artists—and, at the same time, mock[ing] machismo itself.” In The Art of Reflection: Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century, Marsha Meskimmon rules that Benglis “self-consciously [adopted] the swagger of male artists,” holding “a huge erect dildo as though she had a penis” and thereby “usurping and parodying the strutting masculinity of her contemporaries.” While castration fears understandably surfaced in critiques, the indignation caused by the ad is less about Benglis’s gender-bending and more about her rule-breaking, decorum-shattering audacity. You can almost hear Krauss squirming in the sing-songy ire of the white girl in Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda”: Oh my god, look at her [dick].

In an interview with Lucy Lippard for the October 1975 issue of Ms., Benglis agreeably defined her ad as “the ultimate mockery of the pinup and the macho.” If we were to come to an understanding of the image as centerfold, this explanation might finally suffice. But for Benglis, in her later tellings, it became more than a dick pic for parody’s sake, more than a one-off fuck you to Morris or the editors or anyone. Within the context of her previous work, Benglis’s dick extends to her work’s broader exploration of vulgarity. When the art historian and academic Richard Meyer revisited the ad in Artforum three decades later, Benglis told him over the phone that she’d had “a formal need to make the picture … I was studying pornography. I was really studying pornography.” Her sculptural work includes goopy piles of frozen polyurethane foam dripped onto the floor, and voluptuous waves splayed over the gallery wall, writhing midair. According to Pincus-Witten, she was “fascinated with substance and eccentric materials as a function of Expressionist sensibility, [taking] pleasure in vulgarity.” Even in her video work, superimposed takes overlapping and piling up like her orgiastic foam, Benglis was drawn to the medium because, as she told Pincus-Witten, she “saw it was a big macho game, a big heroic, Abstract Expressionist, macho, sexist game. It’s all about territory. How big?”

While Benglis’s is certainly big enough, the dick as we know it also derives its power from stamina. “Taste is context,” as Pincus-Witten wrote in ’74, and those first Artforum ad spots provided a nearly unprecedented context: In one fell gesture, Benglis put both the image on the map and its plausibility as an art work at stake. Context, expressed as taste, behooved Krauss and Michelson to leave the pages of the most prestigious contemporary art magazine in America because both women, as Krauss told the New Yorker’s Janet Malcolm in 1986, “read [the image] as saying that art writers are whores.” Krauss couples the symbolic purity “Art” maintains amid the market’s muck and perhaps even Artforum’s unstained reputation as the singular chalice bearing art’s intellectual and critical capacity above the commercial fray, with a certain sexual reservation, something between outright frigidity and simple, upper-class sangfroid. The artist can promote her work within Artforum as long as she doesn’t sell herself too well in its pages, as long as she doesn’t loiter past the limits of her critique as she would on a street corner, as long as her art work doesn’t get too easily confused with sex work. Otherwise, Krauss argues, Artforum’s editors become pornographers, the rag nothing more than a thicker Playboy. Benglis’s bad taste begins to smack less of phallic bravado, and more of a institutional critique.

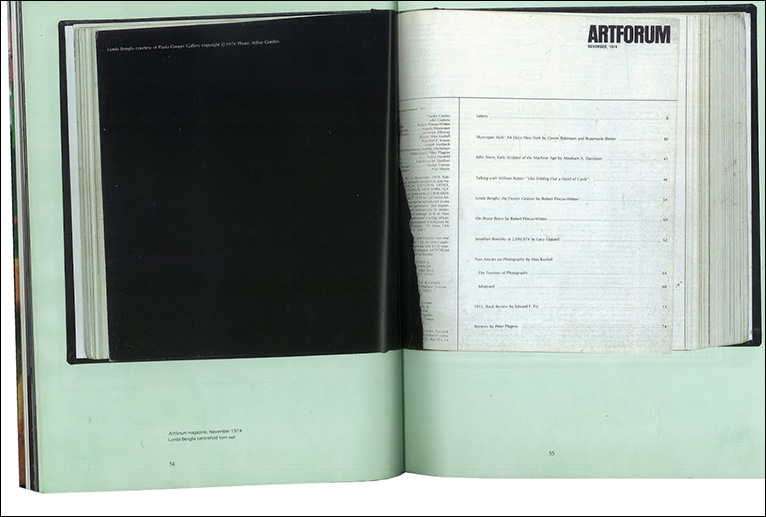

In his 2004 essay, Meyer tells us that whenever he visits a college, he checks the library’s Artforum archives for a November 1974 issue, needing to see for himself her dildo bound within the art world’s masturbatory bible. Usually the page is already ripped from the magazine, victim to either an act of censorship or a theft for personal pleasure. With the image-side of the centerfold missing, we glimpse, instead of Benglis’s package, the issue’s table of contents, revealing, as Meyer writes, “the intimate proximity of commerce and criticism within the pages of Artforum.”

At the college I attended, the library’s Artforum was Beng-less by the time I got there. When I did find the image reproduced in another book—the catalog for the New Museum’s 1994 exhibition “Bad Girls”—I tore it out myself. I’ve kept it taped to my wall since. “They’ll remember you for this,” Benglis’s mother told her 40 years ago. And we have, but rather selectively. Forgotten first in the feminist-art-world outrage over the ad, then in the feminist reclamation of her work, is the fact that most people actually loved it.

In a 1975 issue of New York magazine, Dorothy Seiberling reported that

from Artforum’s “community” of readers, the ad elicited the biggest mail response of anything published in the magazine’s 13-year existence. Far from feeling brutalized or exploited, the majority took the “dissociating” associate editors to task for their “prudish” and “self-righteous” stance which the readers felt was “antithetical to artistic freedom.” Only a handful of correspondents (mostly male) considered the ad vulgar and pornographic.

Four decades have passed and the image, as Roberta Smith recollected in 2009, remains a “lighting rod for conflicting views on feminism, pornography, editorial (and critical) responsibility, art-world economics, reputation-building and artistic license.” Andrea Dworkin’s writing and the anti-porn crusade of the 1980s, David Wojnarowicz’s battles against the NEA’s censorship in the early 1990s, even the overrated fuss following Kimye’s March 2014 Vogue cover: all in some way echo and call back to Benglis.

So. Is it art, is it an ad, or is it porn—or is it a parody of porn? As Meyer writes, the image refuses to fit idly into either “a feminist critique of pornography or a pornographic critique of feminism.” Nor can it be reduced to either an artist’s critique of commerce or a commercial, cynical piss-take on contemporary art. To chalk up its iconicity to the picture’s original sin—its female-to-male transgressiveness—is tempting, but hasty and perhaps ahistorical.

Throughout the 1960s, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama posed naked with phallic objects of her own creation. Her first installation, 1963’s “Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show,” includes a small rowboat floating in an ocean of wallpaper, filled to the brim with small, mushroomy penii. She creates similar infestations on chairs, dresses, shoes. In an interview with Kusama, Akira Tatehata asks,

Tatehata: Is the imagery of phallus-covered furniture related to your hallucinations?

Kusama: It is not my hallucinations but my will.

Tatehata: Your will to cover the space of your life with phalluses?

Kusama: Yes, because I am afraid of them. It’s a ‘sex obsession.’

Unlike Benglis’s later appropriation of male, sexual prowess, Kusama seems to drown in her obsession. Sculptor Louise Bourgeois, on the other hand, plays almost raptly with the phallus. In her 1968 sculpture Fillette, a grotesque two-foot latex penis with a prominent scrotum is hung by a hook from its foreskin. As the curator Marcia Tanner suggests, this otherwise off-putting, phallic cadaver becomes “uncontrollably sweet, [so] that you really want to cuddle this outrageous object.” A portrait of Bourgeois taken by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1982 presents this very image: Bourgeois, dressed in a feathery black coat, cradles her ‘little girl’ with a sly expression.

Although their oeuvres are more consistently complicate the phallic than Benglis’s, neither Kusama nor Bourgeois, nor even the ’60s and ’70s conceptual gunslinger Hannah Wilke, made anything half so blatant as Benglis’s ad. In the decades since, however, we’ve seen dildos pop up in the work of women as disparate as Sarah Lucas, the jokey conceptualist and No-Longer-Young British artist who opened a solo show last November featuring a large metal-casted totem, among several penile puns. Why aren’t any of these works as sticky as Benglis’s ad? Perhaps because, while sometimes more intelligent, thoughtful, or theoretically risky, none are nearly as fun. Almost no appropriation of masculinity by a feminist artist has been as joyful, as pleased, or as pleasurable as this portrait of a woman who spray-tans to match her dick. Kusama seems to be reifying her penis-fear; Bourgeois infantilizes the obsession; Lucas puns. Only Benglis seems to get the joke-not-joke of my own (not so) little “phantom dick.”

I know I am not alone in this. I’ll reference my own dick in passing, either to cheekily state arousal (“I have a huge boner ”) or to assert my superiority in flashes of excessive self-confidence (“I have the biggest dick in the room”). I might even reference my dick during disappointment, point to a flaccid, sunken feel when all hope goes soft. Although there’s a tongue-in-cheekiness to it all, there’s also a slight unease in not only perhaps affirming phallic power but also yielding to it, even in jest. Female art historians writing about the works of Kusama or Bourgeois, for example, offer thousands of words to “problematize” this feminine thing about the phallus. Analysis leads to analysis, someone will bring up Lacan, and Benglis’s fistful ends up signifies nothing more than an empty hand, played as a bluff in a man’s game. But if the metaphorical dick is so mired in patriarchy or psychoanalysis, why does it feel so good?

It’s worth remembering that Benglis’s dick, even if a mockery, is also a threateningly perfect mimicry. Her dick necessitates a double take every time. It’s double-headed, too: a masturbatory aid primarily used for queer fucking. Benglis’s dildo is what queer theorist Lynda Hart inspiringly, and a little tendentiously, has termed the “lesbian-dick:”

It neither returns to the male-body, originates from it, nor refers to it. Lesbian-dicks are the ultimate simulacra. They occupy the ontological status of the model, appropriate the privilege, and refuse to acknowledge an origin outside their own reflexivity.

In Lesbian Art: A Contemporary History, artist Harmony Hammond asks, Would this work have been received differently had Benglis been a lesbian? Perhaps then the crudity of Benglis’s portrait would be rooted not only in a negatively defining ridicule of dick-power but also in a hard-earned dismissal of it. Perhaps she wouldn’t have been suspected of something like sluttiness. Unlike so many of her contemporaries and critics, Benglis wanted to have fun—but it wasn’t just that. It was that she was woman enough for herself. The ad assumes dick power while underlining the subsequent fact that, thanks to her dildo, she doesn’t really need it; she wants it, and for a while, anyway, she owns it.

Part of owning a dick responsibly is knowing when to use it and when to put it away. I reference my dick when I own my power, when my desires don’t need to be affirmed but simply materialize, exude from me without dispute, thick blood rushing to my cunt. My dick gives me a rise, reminds me of my own reach. With it, there’s the ambivalence of feeling both satisfied, grinning, and still emptier than before, holding your dick in your hand, striking a hip pose on the threshold of repulsion and engrossment, unsure of which is which.