Like a lot of black girls coming of age in the final years of the 20th century, I had an adolescent fascination with Prince. As an adult I recognize that this fascination was rooted in a certain kind of queerness that Prince embodied. At the time, I didn’t know anything about Prince’s sexuality—other than the fact that it was purple, and he wore it well—but I see now that my younger self recognized Prince wasn’t following the rules about gender that I was in the process of learning. I listened to the seven-plus minutes of “Erotic City” and marveled at what kind of place this might be, even if I didn’t really understand what erotic meant. I watched the sophistication of this petite, light-skinned man in his music videos strutting and spinning in block heels, bouncing pressed and curled black hair that boasted length and body, wearing lace and leather and silk and always, always purple. I didn’t identify with the svelte women in these videos who surrounded Prince, vying for his attention and receiving it coolly, but I did envy them. I don’t understand everything about Prince’s public reception or his gender and sexual identities. The special significance of Prince, for me, lay in recognizing that if he could take the trappings of femininity that seemed so familiar and wear them in a brand new way, then it was also possible for me to wear gender in more than one way. In other words, being femme could be an invention, not just a duty.

Omise′eke Natasha Tinsley, Ezili′s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders. Duke University Press, 2018. 264 pages.

When Prince changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol in 1993, he did it knowing that its unpronounceability would present a problem for labels, distributors, and news media. The demand for legibility is about not just access but also control, and changing his moniker from a proper name to a new and unspeakable symbol allowed Prince (or The Artist) to create a way of being that exceeded the limitations he experienced as a black gender-creative figure in the U.S. music industry. Our language, even the technical language of queer studies and queer theory, doesn’t always fit the realities of queer lives in the African diaspora as they are lived and portrayed. But like the symbol used by Prince to reflect something else about himself as a performer and a person, there are other possible languages and other modes of address. By showing how available language doesn’t necessarily fit the realities of black queer lives, Prince was also making a statement about our shared epistemology—the ways that we are able to know and make sense of the world.

Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley’s book Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders (Duke University Press, 2018) is also interested in the way that black queer folks, particularly femmes, enact gender creatively through musical and theatrical performance, hair salons, and choreography. In the West, race is gendered and gender is raced, as black-feminist scholars across multiple disciplines—history, sociology, gender studies, literary study, and others—have emphasized. This has meant that the social and cultural roles allowed or imposed on black women have differed from those allowed for white women. Tinsley gives an example of this thought and practice by noting that in the 18th century, many Caribbean colonies had laws that prohibited black women from wearing shoes. This served to reinforce and reflect economic inequalities, of course, but also to crystallize the distinction between white “ladies” and black women. With recognition of this history of blackness occupying the abject and/or undesirable position in western gender systems, Ezili’s Mirrors works to trouble common-sense understandings of how race, gender, and personhood are linked.

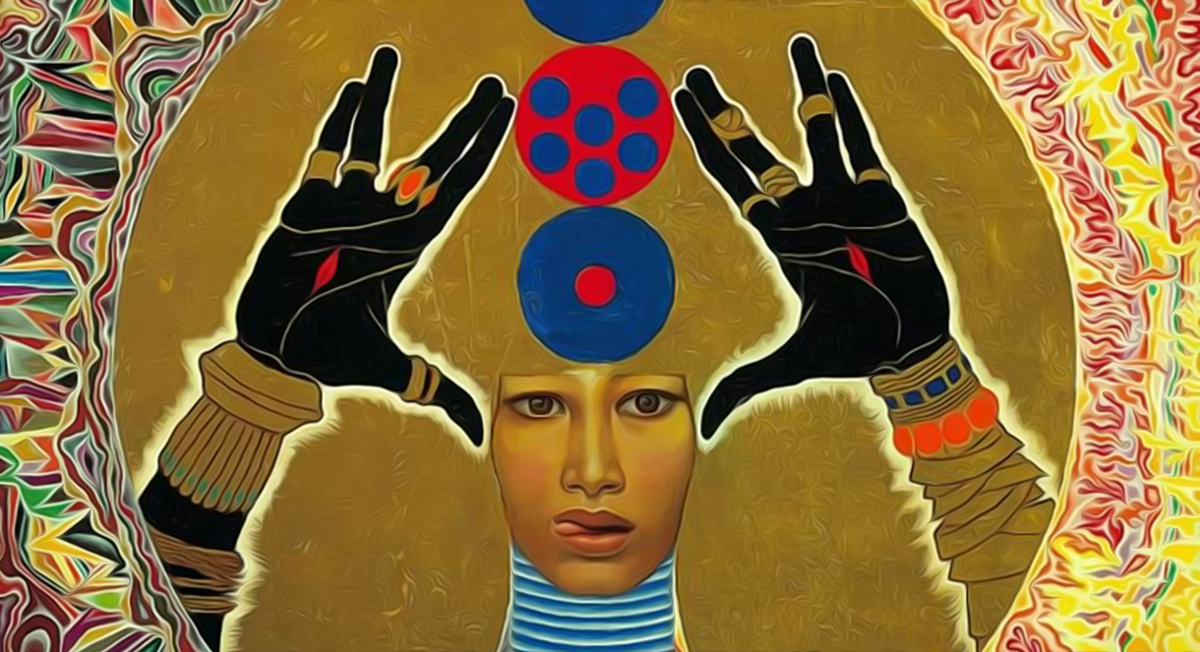

In this vein, femme is developed in Ezili’s Mirrors as an expansive, queer gender identity that can both encompass and exceed what we typically understand as femininity. Femme allows space for the gender presentations and performances that might resonate with traditional femininity yet are articulated from queer positions. Another particularly femme method of creatively enacting gender is found through devotion to Iwa, divine forces in the Haitian religion of Vodou. The creativity depends in part on how one engages and/or challenges the available or dominant epistemological framework—in other words, one’s worldview. Just as we depend on mirrors to see ourselves, we depend on epistemologies to make things—concepts, histories, and patterns—visible. What we see in a mirror is delimited by its frame, and epistemological framings allow some things to be visible just as they make it difficult or impossible to perceive other things. Aside from the title, mirrors in this text are present as tools in the hands of performers, Vodou practitioners, or literary characters. However, the conceptual role of mirrors provides the basis for a key insight of this book: Mirroring provides ways of seeing iterations of the Iwa, the possibilities of gender and sexuality, and ultimately oneself multiply and creatively. For black people, particularly black queer femmes, the gendered, sexual, and racial realities revealed through worshipping Ezili present challenging alternatives to their positions suggested by Western epistemology.

Western epistemology is not a fully encompassing term but rather a shorthand for some of the common sense of life in Western modernity: Concepts like Cartesian dualism or the mind-body split and the predominance of sight as the sense through which truth is attained are examples of the philosophical precepts that form the basis of other assumptions about what constitutes knowledge in the West. Rather than taking these epistemologies for granted and assuming that they can adequately capture all experiences of the world, one of Tinsley’s projects, and a project of black-feminist writing more broadly, is to introduce other epistemologies to the reader’s framework.

One such epistemology Tinsley introduces is a spiritual epistemology. She encourages us to consider Haitian Vodou as one that offers more conceptual space, more ways of understanding gendered and sexual experiences, identities, performances, expression, and practices, than Western epistemologies traditionally have, at least for queer people in the African diaspora. Practitioners of Vodou are thus able to access and understand their own genders and sexualities, as well as those of others, in terms that exceed and perhaps fundamentally differ from those available in North American queer-studies circles. It’s significant that this epistemology is a spiritual one, particularly in an academic space that makes so little room for unquantifiable and nonrational ways of knowing. This practice of recognizing that there are not just other experiences but even other ways of making sense of the world, is for Tinsley a key practice of decolonization.

As the title suggests, the Iwa in focus in this book is the goddess Ezili. She has multiple iterations, or faces, and her pantheon represents “love, sexuality, prosperity, pleasure, maternity, creativity, and fertility.” Each chapter is organized around one such Ezili and highlights literary texts, historical narratives, performance art, and contemporary practitioners whose work reflects that Ezili’s face. One chapter centers Ezili Freda, the embodiment of the seemingly unattainable perfection of hyperfemininity: She is adorned in pink, pearls, and perfume. Tinsley reads Ezili Freda and her followers as devoted to reclaiming, by recreating, Western notions of femininity and womanhood that have historically excluded black femmes.

Tinsley illustrates this historical process of black-femme erasure through the narrative of Janet Collins, a New Orleans–born Creole dancer who became the first black prima ballerina in the United States. Collins’s career through the mid-20th century was marked by this accomplishment but also by various institutional attempts to manipulate her blackness in order to make her womanhood more legible. In Collins’ first role as prima ballerina, she played the title character in the opera Aida, an Ethiopian princess enslaved in Egypt. Tinsley points out two seemingly contradictory ways Collins’s blackness is visible in this production: The “African” setting naturalized Collins’s presence as a black dancer, yet the appearance of Collins’s blackness was visually downplayed. During the climactic scene, the entire cast of white dancers was painted with dark brown makeup. Tinsley suggests that the contrast of Collins as heroine—despite being the only black dancer—as the lightest figure on stage reinforced for white audiences the “natural” link between whiteness and femininity. Despite these kinds of manipulations, Collins used choreography, her art and profession, as a tool to create the kinds of womanhood onstage she saw as possible for herself and for other black femmes. Janet Collins is linked with Ezili Freda because both are made brilliant and awesome by their unlimited creativity. But just as Janet Collins’s creative potential was tempered by the realities of antiblack racism, Ezili Freda’s pursuit of perfection is always tempered by her confrontation with the limitations and injustice of the mortal world.

A similar structure characterizes the other three chapters of this book. Ezili Danto, the protective mother whose presence was said to initiate the Haitian revolution, is read with the queer and creative parenting of Angie Xtravaganza, famous in New York’s drag ballroom scene as the house mother of the House of Xtravaganza. We meet masisi—a Haitian Kreyòl term that captures “a spectrum of transfemininty”—devotees of Ezili Danto who make markets and hair salons their space for building gendered community. Another chapter is dedicated to Erzulie, the cosmic dominatrix who demands justice and obedience. This Ezili’s signature color, red, is visible in the figure of Domina Erzulie, a BDSM- and Vodou-practicing Montreal-based dominatrix who charges white men to draw their blood and drown them in golden showers. Erzulie’s penchant for domination as a way of extracting justice is historically mirrored by Mary Ellen Pleasant, a black 19th- and 20th-century San Francisco entrepreneur and abolitionist who built her business empire by serving the domestic needs and sating the sexual interests of San Francisco’s wealthy white elite.

Tinsley opens this book by asking her audience to read it like a song. Academic texts are known to make more or less sincere overtures towards democratizing their work, but this is a request Ezili’s Mirrors takes seriously. There are three alternating fonts, or voices, used throughout the book: academic knowledge, spirit knowledge, and black-feminist ancestral or historical knowledge. When introducing these alternating voices Tinsley asks us to hear them the way we might listen to a Destiny’s Child song: Even if the traditional theoretical tone is centered like Beyoncé, the voice of spirit-based knowledge is rich and powerful, like Kelly Rowland, and the voice of ancestral knowledge provides an underacknowledged balance, like Michelle Williams. The three voices are not always in perfect harmony. Sometimes it’s hard to know why this narrative is sung by this muse, and it isn’t always easy to visually distinguish between the three. However, if you focus less on trying to strictly categorize each voice or font, and instead lean into the surprises of what Tinsley terms the book’s “unresolved plurality,” it may be easier for you to tune in and let the song overtake you.

This book’s register invites an intimacy that comes from Tinsley’s choice of audience. She doesn’t dictate or restrict who can read her book, of course, but Ezili’s Mirrors is a song “dedicated to black queer femmes.” The directness of this address is part of what I found so compelling in reading this book: She’ll ask us, her chosen audience, to engage, to listen more closely, to be patient with sections ahead—and this directness works to collapse the gulf between writer and reader that is often characteristic of academic, theoretical writing. Tinsley takes a range of black queer femme figures—mortal and divine, Haitian and Dominican, contemporary and ancestral, cis and trans, famous and obscure—and invites us to listen and watch as she identifies the salient notes and features of the narratives of their lives. Some terminology notwithstanding, Ezili’s Mirrors is largely accessible for readers who are interested in the text not primarily as an academic project but rather as an exploration of narratives and perspectives that are too rarely made visible in mainstream academic and popular media spaces.

Committing to that intimacy and challenging the familiarity of the author-reader gap is an enactment of Tinsley’s black-feminist political and intellectual practice. Another black-feminist practice is Tinsley’s incorporation of her own sensuous, reflective memories as part of her narration and theorizing. For example, while considering the importance and radical possibility of queer parenting practices, we are invited to witness Tinsley’s narration of experiencing two miscarriages while writing. To render this generous and tender vulnerability requires skill and commitment from any writer, and particularly in a text published by one of the most theoretically minded university presses.

Tinsley describes her research and writing methods as not just interdisciplinary but a practice of theoretical polyamory. Just as in romantic polyamory, theoretical polyamory is not an invitation to sloppy, careless, or inattentive promiscuity. Instead, theoretical polyamory as it is enacted here shows an intentional practice of recognizing what each relationship is capable of providing and what commitments are necessary to maintain its health. Scholars of African-diaspora or black-Atlantic studies, Caribbean studies, gender studies, queer studies, literary criticism, media and pop culture studies, and scholars of religion, particularly scholars of Afro-descended religious traditions, will find a complex and multidisciplinary text that illuminates how each of these disciplines are made richer through Tinsley’s interweaving of their methods and questions.

If Ezili’s Mirrors is indeed a song, it is a song in harmony with a huge body of other black-feminist voices: ancestors, theorists, writers, and creators. Folks who are familiar with black-feminist academic work, black-feminist art, and black-feminist literature will all find familiar voices and figures in Tinsley’s writing. Whether they are explicitly cited—like M. Jacqui Alexander, Katherine McKittrick, Kara Keeling, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and Patricia Hill Collins—or unnamed yet visible in words and small phrases—like M. Nourbese Philip, Dionne Brand, and Audre Lorde—black women’s creative works form one of the archives of Ezili’s Mirrors.

By seriously engaging positions rooted outside of Western epistemologies, Tinsley models a multiplicity of ways of knowing and approaching knowledge. More importantly, she takes these other ways of knowing seriously. Ezili’s Mirrors thoroughly and carefully mines the utility and uniqueness of multiple spiritual and thought traditions, aesthetics, and sources of knowledge. This engagement with other epistemologies is not solely accessible through Tinsley’s text or through academic epistemological critique more broadly. The speculative fiction of Octavia Butler and Nnedi Okorafor, the practice of Haitian Vodou and other African-descended religious and spiritual traditions, and even the gender-creative performance of Prince all present ways of accessing nondominant ways of seeing and moving in the world. What makes Ezili’s Mirrors uniquely successful, though, is bringing these alternative images into conversation and articulating how we might already be seeing, engaging, and building our own alternative epistemologies.

Audre Lorde writes in the essay “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference” that truly revolutionary political change depends on extracting “the piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within each of us, and knows only the oppressor’s relationships, the oppressor’s tactics.” Lorde was suggesting what many of us know through experience: that identifying and committing to changing the foundational ways in which we understand the world is a daunting task, even for those elements—colonial or otherwise—that don’t necessarily help us be or live more freely. And yet, people throughout the African diaspora have always found ways to live and define themselves that challenge the singular and dominant framings imposed by colonialism.

Ezili’s Mirrors is important because through it Tinsley shows us ways that black femme life and black queer life exists and asserts itself as other than the abject, the undesirable, the inappropriate, and the excessive. The book illustrates how and why the figures of Ezili, only one goddess among a pantheon, serve as such an effective foundation on which alternate black narratives, representations, and ways of seeing have been built. Tinsley does not suggest that the task of decolonial epistemological critique is easy. The challenge of extracting the oppressor implied in Lorde’s quote is not dismissed. Instead, she proves that it is possible by illustrating how creating and embodying epistemological alternatives has already been and is currently being done across the black Atlantic. Ezili’s Mirrors shows its readers, whatever spiritual, critical, and intellectual traditions they hail from, that for those who walk with Ezili, other worlds than this one are always possible.