The turn of the last century saw the dining room go from a haven in a heartless world to a fueling station for factory work

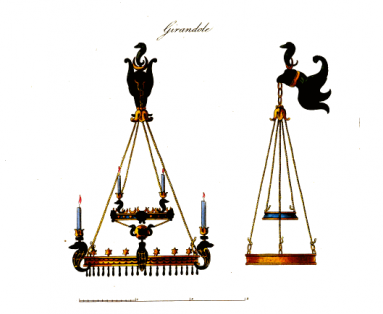

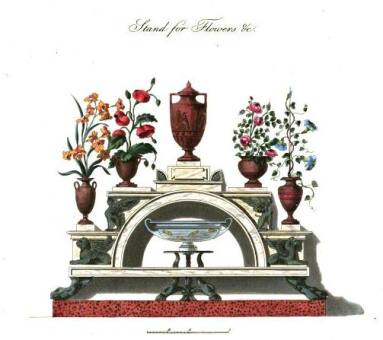

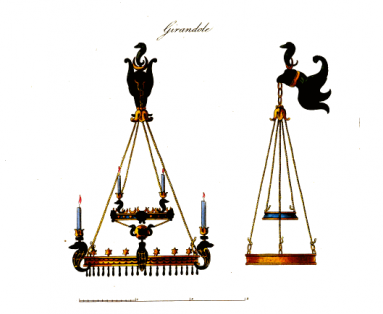

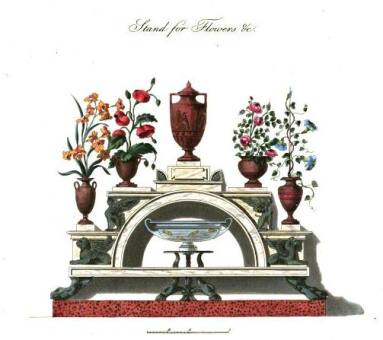

Illustrations from A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1808)

To read part 1, click here.

One summer day in 1894 Walter Post took out a line of credit.

"Is it progress if a cannibal uses knife and fork?" --Stanislaw Lec

The Northern Pacific railroad clerk wanted to spruce up the six-room house he shared with his young wife, Ulilla (neé Carl and known fondly as “Lillie”). To Schuneman and Evans, the department store extending him the loan, he pledged repayment in 60 days’ time.

"Come on, little lady, / Lady, let's eat at home. / Come on, little lady, / Lady, let's eat at home. / Eat at home, eat at home." --Paul McCartney, "Eat at Home" (1971)

While at the job he might any day lose (“The Northern Pacific is in a bad fix,” he noted in a letter to his father) he daydreamed of furnishings. The home’s dining room especially seemed to occupy his thoughts. A sheet of company stationery bearing a rough schematic offers a sense of the careful attention he paid to that room’s decor. A large, inexpertly drawn square represents the solid-oak dining table whose purchase claimed most of Post’s borrowed sum; two or three smaller squares, a retinue of sideboards and china cabinets. Three X's appearing in the corners indicate spare chairs on hand to add to the ambiance and seating capacity on nights the couple entertained. Another X appearing at the head of the table is labeled “My Place”; yet another off to one side, “Lillie’s.” These hand drawings, suggestive of the rich appointments essential to orderly home life, could only flow from the pencil of a man who believed himself newly affluent.

"There was a good dinner enough, to be sure; but it was not a dinner to ask a man to." --James Boswell

"The whole countryside came together, Catholic as well as Protestant, the Christian and the pagan and even the hermit ... A very old part of the program of religion is eating together. It is much older than preaching, and I claim that if we cannot have preaching in our country church program, we must keep in it the common table." --Wisconsin Country Life Conference, Vol. 2 (1912)

No incautious striver, Post simply wanted a stylish and comfortable place to enjoy his meals. This desire he shared with many of his fellow Americans who, aided by lower food prices and new wealth following advances in transportation (rail, sea) and industry (finance, oil), made eating at home an art. Housewives hurried to market to purchase large, well-marbled joints, along with pineapples, oranges, and other then-exotic fruit. Like Walter and Lillie, they spent lavishly on their dining rooms, outfitting them with upholstered chairs, mahogany sideboards, pewter jugs, bone china, linen napkins and tablecloths, and silver cutlery. They read architectural guides and kitchen utensil catalogs as thick as phone books. Deviating from the precedent set by their stalwart colonial ancestors, who took their meals when and how they could get them, 19th-century Americans treated mealtime as an event, staging the satisfaction of their appetites in surroundings as comfortable as they could afford.

"We serve food attractively. We remember that smell and sight are taste's silent partners and we try in every way to meet their requirements as well as those of taste. A banquet, a luncheon, a camping supper, a 'club feed,' are only incidentally nourishing. It is the social element and the festive and artistic element that give them their charm. We share the deep-rooted instinct of the ancient peoples, to whom eating together was the highest form of companionship." --Marion Florence Lansing, Food and Life (1920)

Americans weren’t alone in their newfound love of creature comforts. A revolution in dining was happening the western world over. Across the Atlantic, the British found in the cozy rituals of dinner a way to act out national ambitions. Architects and domestic experts wrote vast tomes on how the home could influence character. And what shaped character shaped also the family and the nation. The dinner is “the symbol of people’s civilization,” wrote Robert Laird Collier in his 1886 domestic manual

English Home Life. “A coarse and meanly cooked and raggedly served dinner expresses the thought and perhaps the spiritual perception of a nation or family.”

"It seems strange at first sight that eating together, even of common food, should be one of the best means of bringing people together. The reason is not in the food itself, not in a mere sensual act, but lies in the fact that eating together is the easiest means of acquaintance." --Select Notes: A Commentary on the International Lessons (1911)

No self-respecting middle-class family wanted to seem mean or ragged, especially in a time when being mean and ragged was only a lay-off away. With guidance from Collier’s domestic manual and others like it, British housewives filled their homes with the necessary domestic equipment for the purpose of turning them into veritable incubators of a moral and productive citizenry. The dining room became the main site of this incubation. By the second quarter of the 19th century, many townhomes featured two rooms for eating, one close to the kitchen for informal family meals and another for formal, public events. This second, more elegant room displayed the family's fashionable decor: gas chandeliers, heavy tapestries, and tables and chairs of black walnut or some other expensive wood. Elaborate sideboards displayed dozens of china, silver, and glass objects. Hulking centerpieces of silver and glass rose from an enormous table draped in damask. Masses of ferns hung from the ceiling and palms occupied gilded planters. Complicated flower arrangements sat in strategic spots throughout the room, and lamps or silver candelabra equipped with wax candles and colored shades lit the whole scene.

"Ever eat a cold lunch on a chill winter day? Then you can understand the lack of energy felt by the worker who eats his mid-day meal from an uninviting dinner pail. But give him hot food -- freshly cooked in his own cafeteria -- then note the difference. He goes at his work with new vigor -- increases his output because he has been supplied with the fuel that builds man power. Plants everywhere have learned by actual experience that warm meals overcome the depressing effect of winter's chill -- their workers have been more efficient since cold dinner pails and unhealthy neighborhood lunch counters were supplanted by Van Range Factory Lunch Rooms." --From an advertisement in Factory, the Magazine of Management, Vol. 28 (1922)

People living today would likely find the dining rooms of yesteryear to be about as roomy and airy as a rabbit warren. But to the Victorian middle class the home offered a “haven in a heartless world,” as writer and social commentator Christopher Lasch would put it, and its clutter symbolized certainty in a society grown increasingly uncertain. Toward the end of the 19th century, London and other cities had become crowded, inscrutable places. The poor roamed the streets in quick, ever-morphing masses. Victorian sociologist Charles Booth wrote that this “huge population” was found to be “poorer ring by ring” as you neared the city's center. At its heart there “exists a very impenetrable mass of poverty.” In many districts, these people were “always on the move, drifting from one part of it to another like ‘fish in a river.’” The specter of this immense, milling crowd haunted the minds of respectable shopkeepers, schoolteachers, and sociologists. It seemed that only an expensive sideboard or china closet kept them from joining the ranks of beggars and underemployed workingmen and prostitutes -- the inhabitants of “a dark continent that is within easy walking distance of the General Post Office,” as George Robert Sims wrote in his bestselling 1881 exposé on London’s poor.

"'We had a dinner party here in this flat about a week ago, and we haven't gotten over it yet,'" said our genial host, as he adroitly raised the gay Mexican blanket that draped the couch, and reached around under that useful piece of furniture with a long cavalry saber.'" --Jean Urquhart, "A 'Flat' Dinner Party" (1904)

Things were much the same in the United States. Walter Post likely risked his credit because he wanted to distinguish himself from his less affluent neighbors in St. Paul, Minnesota. “Social and economic heterogeneity was the hallmark of the age,” writes Stephanie Coontz. “Most areas of the big city were a jumble of occupations, classes, shops, homes, immigrants, and native Americans.” A clerk with ambitions of respectable middle-class life might find himself living a few houses down from foreigners and factory workers. Even if he didn't, the possibility was enough to make him stuff his home with the furniture and bric-à-brac he believed symbolic of his superiority.

"On the Continent people have good food; in England people have good table manners." --George Mikes

Yet furnishings weren’t enough to distance the middle class from its inferiors. The respectable bourgeois had to cultivate good manners as well. “A man may pass muster by dressing well; and may sustain himself tolerably well in conversation, but if he be not perfectly ‘au fait,’ dinner will betray him,” said an author of one of the many etiquette guides that appeared during this period. Meals became formal events with decorous protocols of their own. The proper meal hour, the etiquette for serving and eating various courses, the appropriate attire, the dining room’s furnishings, the seating arrangement, the fit subjects of conversation, even the food itself — these innumerable punctilios came to form a sort of rubric governing mealtime conduct. It didn’t help that this rubric changed often. In the 1850s, etiquette dictated that fish be eaten with just a fork and a crust of bread. Not 30 years later this practice was deemed barbaric.

"What would you have done with this mother's problem? ¶ The problem was a little girl, seven years old, and her table manners, or rather, we should say, her lack of table manners. For she had none, except very bad ones. She was growing very fast and was always ravenous at meal times and if she was not served before everyone else she was very ugly and impatient about it. When she did get her food, she would not stop to cut her meat, usually taking it up in her fingers, as she did much of her food ... The description is not exaggerated. The child reminded us of the pictures and accounts of the meals of cannibals, of cavemen and even of animals. We are not, perhaps, descended from cannibals or from animals, but there is no doubt about our being from cavemen, who knew nothing about such refinements as table manners." --from The P.T.A. Magazine (1919)

Nonetheless, the importance of being earnest in learning and adapting to the dinner hour’s mutable rules itself remained pretty much constant. Notions of civility depended on it. “Show me the way people dine and I will tell you their rank among civilized beings,” wrote Charles Darwin. Parents saw to it that their children’s civilizing began early in life. Wayward youngsters often found themselves sent from the dining room to await a scolding or confinement. Indeed, the highchair, that fixture of every home housing tots, owes its existence to Victorians, who invented it as a means of keeping tantrums from spoiling the prandial ritual.

"Q. How do you employ yourselves on Sundays? Give a general description of the life of factory people on Sunday. A. Some different from others, of course; I generally lie in bed until about seven o'clock Sundays. Then we both get up and get the children ready for Sunday-school and send them to school, and then it takes wife and me about all the time to wash, clean and scrub up the house, and cook the extra dinner for Sunday, so we can have a comfortable meal. We have warm dinners on Sunday. In the afternoon we sometimes take a nap. Then I get supper and take a walk round and get myself ready for Monday morning again. Q. You describe the common factory life on Sunday? A. So far as I am concerned, it is about so. Q. Why do you not attend church on Sunday? A. I really have no time, because if I went to church, my woman would have all the work to do, and it would take her all the day Sunday, and that would be seven days' work, and I would be resting and she working, so I stay at home and help her, and we get through just in time for dinner, and then we take a nap and take a walk in the afternoon." --From Factory Children (1875)

"Are the work-people or children ever allowed to leave the factory during working hours? -- No; except they give warning to go off sick. What time are they allowed every day to quit the factory to get their dinner? -- They are allowed no time, only one day in the week to get their dinner." --From "Reasons in Favour of Sir Robert Peel's Bill, for Ameliorating the Condition of Children Employed in Cotton Factories" (1819)

Yet the Victorians later found that work got in the way of proper dining. The latter half of the 19th century saw working- and, to a lesser extent, professional-class households obliged to adapt their lives to the ringing of the factory bell. This took some getting used to. In earlier decades, wives and mothers had welcomed their families to dinner between noon and one. Children rushed home from school, fathers from field, office, or workshop. The working day’s hiatus, the dinner hour was a time to relax and chat about recent events. By the late 19th century this tradition had largely vanished. “The family dinner at midday,” lamented one urbanite in 1875, “and the evening tea of inland towns, at which parents and children gather about the tables and learn to know one another through the interests and feelings of everyday are almost unknown in the same grade of social city life.” Families in the city postponed their main meal to the evening hours. Those working in factories did so as well; but often the paterfamilias was kept late, and the bread he won he could only break with his family on Sunday.

The arrival of the 20th century saw the kitchen replace the dining room as the main room for eating; because work trumped leisure, eating meals in the kitchen offered greater convenience. The change in venue reflected the fact that many families of the time concerned themselves more with individual health and productivity than musty Victorian morals and manners. “The Progressive ideal of efficiency and the newly energized middle-class and elite commitment to the preservation of health and fitness helped alter the older ideology and the look and function of the home,” writes historian Harvey Green. “The kitchen and bathroom became focal points for advice and criticism, superseding the previous era’s concentration on the parlor and dining room.”

"Brain workers need proper brain food. Certain foods stupefy brain action. Other foods are full of brain building material. With good health the greatest single asset to business achievement, executives should choose foods producing brain power, vitality and longevity." --From "Keeping Fit for the Business Battle," The Magazine of Business, Volume 32 (1917)

"For the man who works with his brain, a very different diet is essential to that of the man who works with his hands. The brain worker should not begin the day with a heavy breakfast. A light breakfast beginning with a cereal -- Grape-Nuts for instance, because I believe that this particular cereal contains the largest amount of nutrition with the least tax upon the digestive organs -- with cream and sugar, fruit, a couple of poached eggs and toast, is amply sufficient food until the luncheon hour, when another light meal -- a hot roast beef sandwich and a cup of tea or milk -- will tide the brain worker over until evening when the principal meal of the day should be eaten." --From "Causes of Indigestion," American Housekeeper, Volume 25 (1911)

Early 20th-century home kitchens served as laboratories for testing the latest popular dietetic advice. They were clean, well-lit places outfitted for efficient meal preparation and distribution. The meals that issued from them were airier yet more nutritious than the puddings and fatty joints of yesteryear, and they were eaten in more a spartan than epicurean spirit. Families nibbled on breakfasts of citrus fruit and dried cereal or eggs and toast. Their lunch consisted of sandwiches, soup, or salad; their dinner, modest meat-starch-vegetable trios and light desserts. (This pattern endures as the one most Americans observe.) A dieter might refuse the plate before him without offending, for eating had achieved an instrumental importance on par with its biological. How and what one ate could whittle waistlines, shape temperaments, or otherwise effect changes necessary for staying light on his feet in the rat race. “Good health is magnetism,” read a 1924 ad for the California Fruit Growers’ Association’s Sunkist Oranges. “It wins people to you, makes it easier for you to influence others, whether you are a salesman, department head, manager, or chief executive.”

Recipe for Family Soup from Breakfast, Dinner and Supper, or What to Eat and How to Prepare It (1897): "Time, 6 hours; 3 or 4 quarts of the liquor in which mutton or salt beef has been boiled. Any bones from dressed meat, trimmings of poultry, scraps of meat or 1 pound gravy beef, 2 large onions, 1 turnip, 2 carrots, a little celery seed tied in a piece of muslin, bunch savory herbs, 1 sprig parsley, 5 cloves, 2 blades mace, a few pepper-corns, pepper and salt to taste. Put all your meat trimmings, meat bones, etc., into stew-pan. Stick onions with cloves, add them with other vegetables to meat; pour over all the pot liquor; set over slow fire and let simmer gently, removing all scum as it rises. Strain through fine hair sieve."

Many Americans today continue to eat for work’s sake. And it seems some of them would like to do away the act of eating itself -- chairs, plates, forks, knives, and all. The meal substitute Soylent, for example, promises to “free your body” from the apparently inefficient rigmarole of meals. Yet what this frees you for is anyone’s guess. (“More work” is the likely answer.) Our Victorian ancestors made eating as stylized as possible not only to display what power and wealth they managed to gain, but also to distinguish what happened in the home from what happened on the job. Their Jazz Age counterparts were the first to transform the home into an extension of work; the working day began at the breakfast table. Now, in Soylent and various other "life hacks," the inefficiency of work’s having to wait until you finish your toast and eggs has found its killer app.