Though not always a smorgasbord, meals enjoyed by Norsemen sometimes offered a little taste of Valhalla

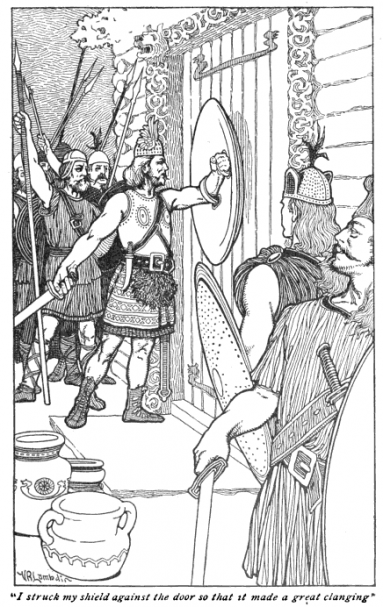

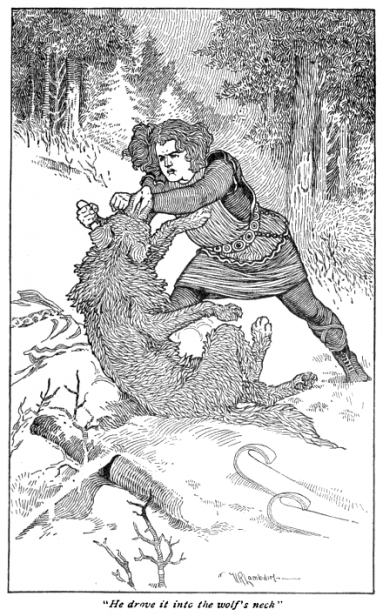

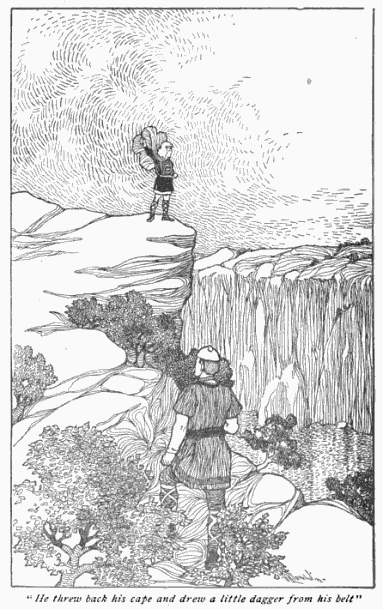

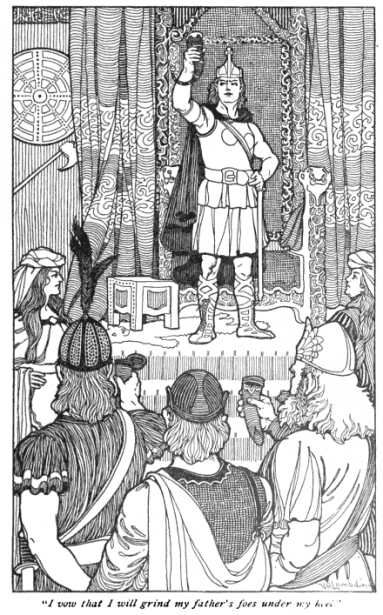

Illustrations from Viking Tales (1902)

"A kind word need not cost much, / The price of praise can be cheap: / With half a loaf and an empty cup / I found myself a friend." --From the Hávamál

It always surprised me that, though she hailed from a small island (little more than a rock, really) tucked away somewhere along Norway's bleak coastline, my grandmother didn't like Norwegian food. She had no truck with boiled cod. Nor did she like boiled carrots, boiled potatoes, or even boiled swedes. Reindeer meat was alien to her, elk meat revolting; and never once did I see her eating those wonderful pork and veal meatballs Scandinavians usually seem to relish. Only on Christmas Eve would she revert to type and prepare a great steaming pot of rice pudding doused in lingonberry syrup. This she ate with gusto. Otherwise her favorite meal consisted of a generous slice of Entenmann's cake, a cup of coffee and a Virginia Slim cigarette.

"They [the Vikings] were like England in the nineteenth century: fifty years before all the rest of the world with her manufactories, and firms and five and twenty before them with her railways. They were foremost in the race of civilisation and progress; well started before all the rest had thought of running. No wonder, then, that both won." --Professor George Dasent (ca. 1861)

Now that I think of it, my grandmother never spoke much of Norway at all, at least not to me or anyone I knew. Perhaps she thought no one would be interested in that frigid, twilit land. She would likely have been surprised to learn that a little over a century ago, Viking lineage was a source of pride.

Publications on Old Norse culture started appearing as early as the 16th century.

It all started in 1867, when excavators digging in a burial mound on a farm outside of Fredrikstad, Norway unearthed a ship some 70 feet long. Below decks tufts of juniper and moss adorned a burial chamber in which lay the remains of a man and two horses. A third horse lay just outside it, along with a sword hilt, two spearheads, a shield boss, a bit of broken ski, and some carved pieces of wood of unknown purpose. Some two weeks after discovering it, they placed it aboard a barge bound for Oslo, the country’s capital.

"Yes, there is perhaps more of Norse blood in your veins than you wot of, reader, whether you be English or Scotch; for these sturdy sea-rovers invaded our lands from north, south, east, and west many a time in days gone by, and held it in possession for centuries at a time, leaving a lasting and beneficial impress on our customs and characters. We have good reason to regard their memory with respect and gratitude, despite their faults and sins, for much of what is good and true in our laws and social customs, much of what is manly and vigorous in the British Constitution, and much of our intense love of freedom and fair play, is due to the pith, pluck, enterprise, and sense of justice that dwelt in the breasts of the rugged old sea-kings of Norway!" --R.M. Ballantyne, Erling the Bold: A Tale of the Norse Sea-Kings (1869)

The Tune ship, as this archaeological find came to be known, created a sensation. Viking fever swept Europe and North America, and all of culture showed symptoms of it. Architects designed houses to look like dragon ships. Striking reliefs carved into them depicted bold exploits of men with braided beards. Scholars translated Norway’s sagas and Iceland’s Eddas, which in turn inspired countless novels, plays, poems, and essays by Grub Street hacks

Only dead fish follow the stream. --Swedish proverb

. Runic inscriptions fell under the gaze of dauntless autodidacts, as did cryptic Nordic proverbs. One Rhode Island matriarch’s stained glass window depicting the Viking fleet that discovered America found itself surpassed only by a statue, commissioned by another great New England lady, of Lief Erickson, that fleet’s captain. Even blue-bloods warmed to the brutal blond warriors of yore. Queen Victoria claimed no less than the Norse god Odin as an ancestor, and the entire Hanover clan fancied itself descendants of the Viking chief, Ragnar Hairy-Breeches.

"A baneful comet from the Bear / Flamed in the northern sky; / It summoned sinful men to prayer, / It summoned Svend to die. / Beneath its influence malign / The pole star sickly grew; / Too well the meaning of the sign / The aged viking knew." --Hugh McNab, "The Viking" (1906)

Too clean has no taste. -- Norwegian proverb

Whether the Victorian Viking vogue extended to viands is anyone’s guess. It’s safe to say, however, that anyone having had adopted Viking foodways would have found himself better for it. Nutritious even by today’s standards, Viking cuisine made for much of the heathen pluck and enterprise Victorian readers came to admire. Twice a day (mid-morning and evening) the Viking warrior sat down to a groaning board heaped with various fish, meat, vegetables, fruit, and grain, all rather tastily prepared. His soups and stews might feature cabbage, beans, peas, and boiled sea bird’s eggs. (These latter he risked life and limb scaling cliffs to the nests he plundered.) Bear, swine, horse -- these he liked too, and ate often. A whale driven ashore by him or one of his fellows meant weeks of plenty for the entire clan. When whales were scarce, stewed elderberries and apples sustained him, as did the flesh of the great auk, a fat, flightless bird that has since become extinct.

"Eager am I to depart. The Disir summon me home, / those whom Odin sends for me from the halls of the Lord of Hosts. / Gladly shall I drink ale in the high seat with the Aesir. / The days of my life are ended. I laugh as I die." --Death Song of Ragnar Lodbrok

Viking food may have savored well enough, but it lacked imagination. Cooks boiled most dishes in wood-lined pits, whose water they kept piping by tossing in a few hot stones. Some families used soapstone cauldrons suspended over hearth fires. Others simply roasted hunks of meat on skewers over open flame. Yet despite such crude culinary means, very little went to waste. Norsemen and –women put up all sorts of preserves. Leftovers they dunked in lactic acid brine, fish they toted to the smokehouse. The most frugal among them simply suspended surplus meat over the hearth fire, which produced smoke enough to cure it. Whatever milk they didn't drink they made into cheese. Fruit and red algae they left to dry in the fresh sea air.

"Vikings oh! There were so strong / Though these warriors won't live so long." --David Foster Wallace, "Viking Poem" (ca. 1968)

Feast days licensed an upgrade from ordinary fare. On such occasions mead and beer flowed from great drinking horns to open, eager lips, filling bellies and fogging brains. With the pleasure came danger. Legend records the sad fate of Fjölnir, a Swedish Viking king who so besotted himself that he fell into a mead-vat and there met his end. Indeed, merrymakers must have had their share of accidents, because The Poetic Edda contains repeated warnings about the perils of drink. “Over beer the bird of forgetfulness broods,” it warns: “And steals the minds of men.”

Fish in Mould (Norwegian Recipe) from Famous Old Receipts Used a Hundred Years and More in the Kitchens of the North and the South (1908): "Boil 1 large firm-meated fish (rock fish) not quite done. Skin and take out bones, putting the bones, skin and head back, to boil down strong. Have 1 cup of milk, 3 cups of cream. To 1 large soup plate of fish meat put 2 tablespoonfuls of potato flour, pound 1/2 hour, adding a little nutmeg and a tiny bit of mace. As you pound add a tablespoonful at a time of the milk, cream and fish essence. Put in a mould. Put greased paper over the top, bake in cool oven in a pan of water. Turn out of mould, dress with rounds of truffles, make pink shrimp or lobster sauce to serve."

I think even my grandmother would have found Viking mead inviting. And their fruit puddings and honeyed cakes certainly would have tempted her sweet tooth. But as to all the fuss those Victorians made over her marauding forebears, to Norwegian she would have much preferred Danish -- especially if it were raspberry.