[This is the start of two related projects, one on sabotage, one on what I'm talking about as "shard cinema." The essay below provides something like the branching point of origin for both: my lectures at the New School are following the sabotage path, the next writings here will track out the shard tributary into its post-Matrix heartland.]

As those who saw it know, Neill Bloomkamp’s Elysium (2013) was a boring little film. Barring the bright morning star of Fast and Furious 6, Elysium is riddled with the same neurosis structuring most films of its ilk: it yearns to be exploitation cinema – and hail the Halo roots of its interchangeable predecessor (District 9) – but lacks the guts to admit it. Like a savvy navigator of those first-person shooter origins, it advances by taking cover, slipping amongst weighty issues (health care! citizenship! the Global South!) and ample veiling flicks of “The Gimp”

Contrary to the expected froth of interpretation that tailed it like a Dark Knight hangover, the film is wholly uninteresting either “politically” or narratively, and especially where the two meet, in the junction point of its alleged allegories, because a) it is simply boring in that regard, extremely so, and b) it doesn’t tell us that isn’t already confirmed by the basic state of affairs in the world at large.

If anything, Elysium functions best as an accidental prequel to In Time [dir. Andrew Niccol, 2011]: where Elysium ends, with everyone being declared “legal” and hence able to access the magical healing beds, In Time begins some years later, after the ruling classes got their shit back together, answering the universal triumph over death with an equally universal mandatory death penalty that hides under the sign of fairly exchanged time-chits.)

That said, there is a minor aspect of the film’s depicted world of interest, insofar as it does bear on a condition that has been creeping its way into dominance: its treatment of technology. Not the abundance of gee-whiz gadgetry, though. Rather, how a film that features hackers able to bring down class structure itself and bolt a robotic exoskeleton to the bones of a dying man nevertheless still establishes a tremendous, unbridgeable gulf between the production process of those machines and their near magical functions once built.

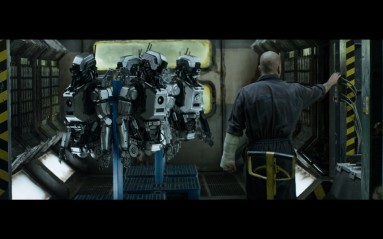

The film goes to great lengths to point out how the advanced technology of this future is still built on Earth, by hand, and in factory. Cops may be expensive automated, irradiated, and Ferrari-red drones, but workers remain meatly human, poorly waged, highly replaceable, and still physically making it all. They weld, bolt, steer, and in the film’s hamfisted Blue Collar echo used to lay a Detroit fog over its favelas, get trapped in a toxic chamber with one of the commodities they have been laboring to build.

What the film never shows, however, is any sense that those same workers who assemble the drone cops or those “healing beds” have any knowledge whatsoever of how they function. How do we know this? Because they never sabotage them to turn the drones to their side, put the muzzle to their absent lips, or at least run with a limp. They never tune the healing beds to give the Elysians syphilis.

Above all, they never make their own. Indeed, the film literalizes its absurd treatment of technology as pinnacle of inhuman mystique by showing “migrants” from earth, Toxic Avenger Lite protagonist included, try to make it through the defenses of Elysium (its space border wall), all in order to sprint over nice lawns, into a mansion, and onto one of the beds. Wouldn’t it be easier, it’s hard not to ask, to just make a version of them on earth? After all, the film implies, they are the ones who make these things. That’s the sole reason the Cosmic North keeps them around: to make the materials needed to keep them making and the Elysians pilates-toned and polyglot. So wouldn’t the workers copy the design? Steal it from the factory, as the song goes, piece by piece? Or, at the least, hotwire it to blow in the faces of those who condemn them to live?

It would be easier, indeed, and more compelling to boot, but we’re left instead with two options.

On one side, the nostalgia for a lost future: a clunkier, notably material version of mid-‘90s (and hence late) cyberpunk ethos, complete with tatted hackers. Yet for all its muttering about healthcare and hence attention to the fragile flesh, it is here so far from a Tetsuo Iron Man lineage - and the maggots swarming around its iron femur – that the very possibility of infection is absent, despite a whole lot of metal being drilled into one human body allegedly just days from death.

On the other side, the film turns around an opposition that stages favela chic, grimy multi-ethnic club scenes (à la Matrix Reloaded), and clunky machines that still have actual keyboards against...

all-white McMansions, well-tailored pantsuits, and sinisterly smooth tech in form of touch screens. The road to the continued hell of class society, the film suggests, is paved with polycarbonite, plus the envisioned drool of audiences who will overcome any moral handwringing to get their smears all over this world of windows, tables, and walls that can be both seen through and mucked around on.

The premise that goes entirely missing is of any possible sabotage, a blindspot apparent not just by the missing act of putting milk fat and sheep shit in the exhaust system of servo-droids but also, more crucially, by the formal ordering of the film as a whole. That is a style and look adequate to a built world of mythical wholeness and neutrality, one that can be “rebooted” with different social content, never mind what they were designed for. The basic nature of this worldview can be seen in a single image.

It twinkles. Advanced technology fucking twinkles, like gossamer, fantasia, or a sequined whatever, while removing late stage cancer from a heroic little girl with not an entrance wound in sight. A pure semblance of effect and counterfactual wishing buffed to a Schein. (Adorno is somewhere spitting in his own grave.) It dissolves cancer, it heals broken bones, yet like the drone-cops, it is never seen as itself capable of breaking down or being encouraged to run riot against its own purpose. Destroyed, sure, defeated because of indefatiguable human spirit / weepy Damon, absolutely. But negated, made badly, ready to blow a fuse or the wall off a condo, never. No, these are integral objects built in accordance with a plan that even those who daily execute it are unable to grasp, stuck tilting instead at cosmic windmills or fleeing into the terrain of immaterial code.

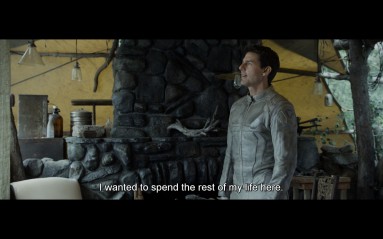

That opposition - nostalgia for the hand-hewn vs. suspicion for the shiny, miraculous things from which you cannot tear your eyes – finds confirmation wherever “single origin” coffee is served, but it is taken to even more insupportable extremes in Oblivion, Joseph Kosinski’s recent Tom Cruise vehicle concerning a blighted earth (and the continued creepiness of a Cruise who seems to be aging in reverse). The plot is as irrelevant as that of Elyisum, because what matters is how its details morally confirm the ordering of its screen space into that same opposition.

Giant, drool-worthy/drool-proof tablets/tables = evil and sterile, however tempting.

Brooklyn salvage cottage, complete with well-worn wood and - gasp! - actual books as last outpost on a blighted Earth = good, complete with impregnable French model.

No utopia in this zero sum game, though.The choice on offer is between

huffing the dried head sweat of Tom Cruise in the middle of an Anthropologie spread (and nearly coming while doing so) or

facing at an infinite series of Tom Cruises (with equal measure Andrea Riseboroughs).

However, the simple collocation of alien hostility with cold spaces that lack twee bottles and driftwood is obvious enough. After all, it’s an autophagy of viewing, a needling suspicion of those smooth surfaces that are the ground of its and our vision, given that all surface textures are, for digital cinema, mere after-effects, just cladding wrapped over skeletal frames, providing the profoundly superficial its camouflage of depth.

So for all its fantasies of “rebooting” (a very hard nuclear reboot in Oblivion, a gentler one in Elysium’s vision of curing the Global South by changing their designation to “citizen” in a databank), this vision cannot help but confirm and deepen that split. It insists that no articulation is capable of finding a lived critique of capital within its own manifest contradictions, other than sheer suicidal exodus and Wall-E-primitivist flight back to the earth.

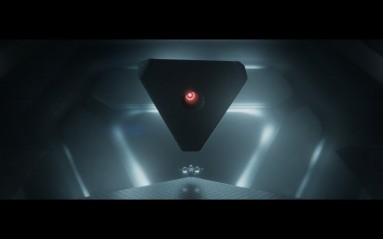

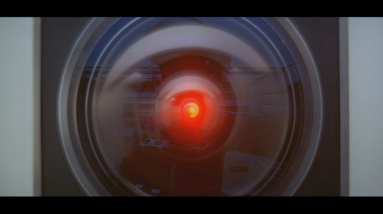

Neither of those get their hands messy with the systems they dream of fleeing, leaving intact the magical vision of an integral and autonomous technology. The faceless figuration that Oblivion gives to it is a fitting one, hailing not just a sharp, levitating, and cyclopean thing difficult to anthropomorphize but also a cypher for the gap between the virtual and the actual, or, more simply, between the possible (and intended) function of a complex technical apparatus and its actual busted/non-functional/murderous state. After all, the echoes are thick. Not just Hal from 2001

itself hailed in the Sauron’s eye of the Motorola Droid phone

but also an apparatus that itself models, manipulates, and destroys such digital images:

the XBox 360 in its moments of failure, specifically the “red ring of death,” an endless half-sleep of being on and yet not functioning.

The name is, of course, a reference to the blue screen of death (Windows), with futher riffs in the spinning beachball of death (Mac), the yellow light of death (PS3), and hot on the market...

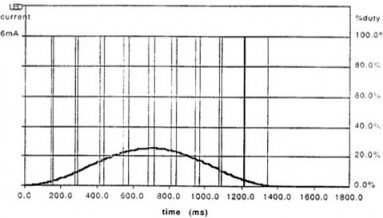

the Blue Light/Pulse of Death (PS4), a problem plaguing the recently released “next gen” system. Despite the Blue Light signifying a coma of processing, the pulse is rather soothing – at least to those removed from the apoplexy of owners of brand new useless slabs – with echoes of Apple’s “Breathing Status LED Indicator,”

introduced in 2002, that little LED that fades in and out in to the rhythm of adult resting breath, 12-20 breaths per minute. (Because they determined it to be “psychologically appealing,” and, I suspect, to naturalize the act of waking to find that you have been spooning an Air.) The Blue Pulse of Death shares the mood of that, a slow gliding cobalt, like sleep washing the toxic silt off memory, but unlike the Mac, it is not sleep. It is life itself in its dumbest form, merely existing, endlessly starting up and getting nowhere, not working, just sort of minimally functional.As for why they are failing to do more than just be: standard failure rate perhaps, or perhaps “shipping errors” of the pre-holiday frenzy (as Sony started to claim). Yet there is another explanation floating around the tubes. The PS4s are being made in China at - wait for it - a Foxconn plant.

The labor there involves not just the normal hell of Foxconn abuse but also the “intern labor” of thousands of students from Xi'an Technological University North Institute. They are there “voluntarily,” but like so many “volunteer” opportunities, it’s a choice at rifle’s end: if they refuse to participate, they lose six course credits, which means they cannot graduate. So into Foxconn they go, where they are paid an entry-level wage, work full time, and then were were forced to working overtime and overnight without extra pay. To be sure, one could imagine tech students gaining “valuable job experience” (Foxconn’s words) from a potentially technical task. Not in this case. According to reports, a finance and accounting major was made to glue together PS4 parts. Another student: peeling off the PS4’s protective plastic and putting stickers on it. Another: putting cords in the box console’s box.

What is the connection with the Blue Pulse of Death? Recently, on an IGN thread for that university, someone claiming to be a student claimed that they had all, in fact, been sabotaging the PS4s. The title of their statement is: "Since Foxconn are not treating us well, we will not treat the PS4 console well. The PS4 console we assemble can be turned on at best."

In the body of the statement, it reads:

“Foxconn doesn't treat us as humans. So we don't treat their products as high quality products. At best, the machine will turn on. Ha ha! The day the PS4 officially launches will be the day Sony and Foxconn go out of business.”

Here, in these years increasingly structured between the double dead end (the magically smooth and the preciously repurposed) visible in those same films destined to be watched on PS4s, sabotage of the form that emerged and was theorized in the late 19th and early 20th century shows itself wholly operable. However, not just because production is here attacked invisibly, a war on unfairly extracted time that makes temporal lag its weapon, inserting a gap between act and effect (the condition that has made sabotage always powerful and always interpreted as sneaky and devious). It also doubles back to what was called the “guerilla fighting” of rapid industrialization because it enacts a practice of refusal that does not take flight from the circuits of capital. Instead, it forms a deep bond with the failure, breakdown, frictions, and loopholes encoded in the very arrangement of those circuit’s. The hypothetically unskilled, called in on false pretenses to be worked beyond contract, show themselves able to learn quickly the minor deviations necessary to put out of commission a complex thing in such a way that they aren’t immediately noticed by bosses.

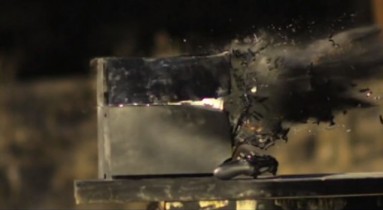

(PS4 being shot with rifle by disappointed owner)

(PS4 being shot with rifle by disappointed owner)

The affinity does not remain technical. It also becomes a blurry doubling of product and producer, to become as non-functional as the commodity and vice versa, a negative feedback loop of identity through non-collaboration with the intended flow of value extraction. Both the PS4 (technically on, with its blue pulse coma) and the interns (technically skilled, but there to just put things in boxes) are reduced to being technically alive but without properties.

If, in the long history of sabotage, the central slogan was “for bad wages, bad work,” the Foxconn action articulates a version all too fitting for the continually hemorrhaging bond between meat and time, bodies and capital: “for a degree zero of work, a degree zero of life. Able to be turned on and that’s it.”