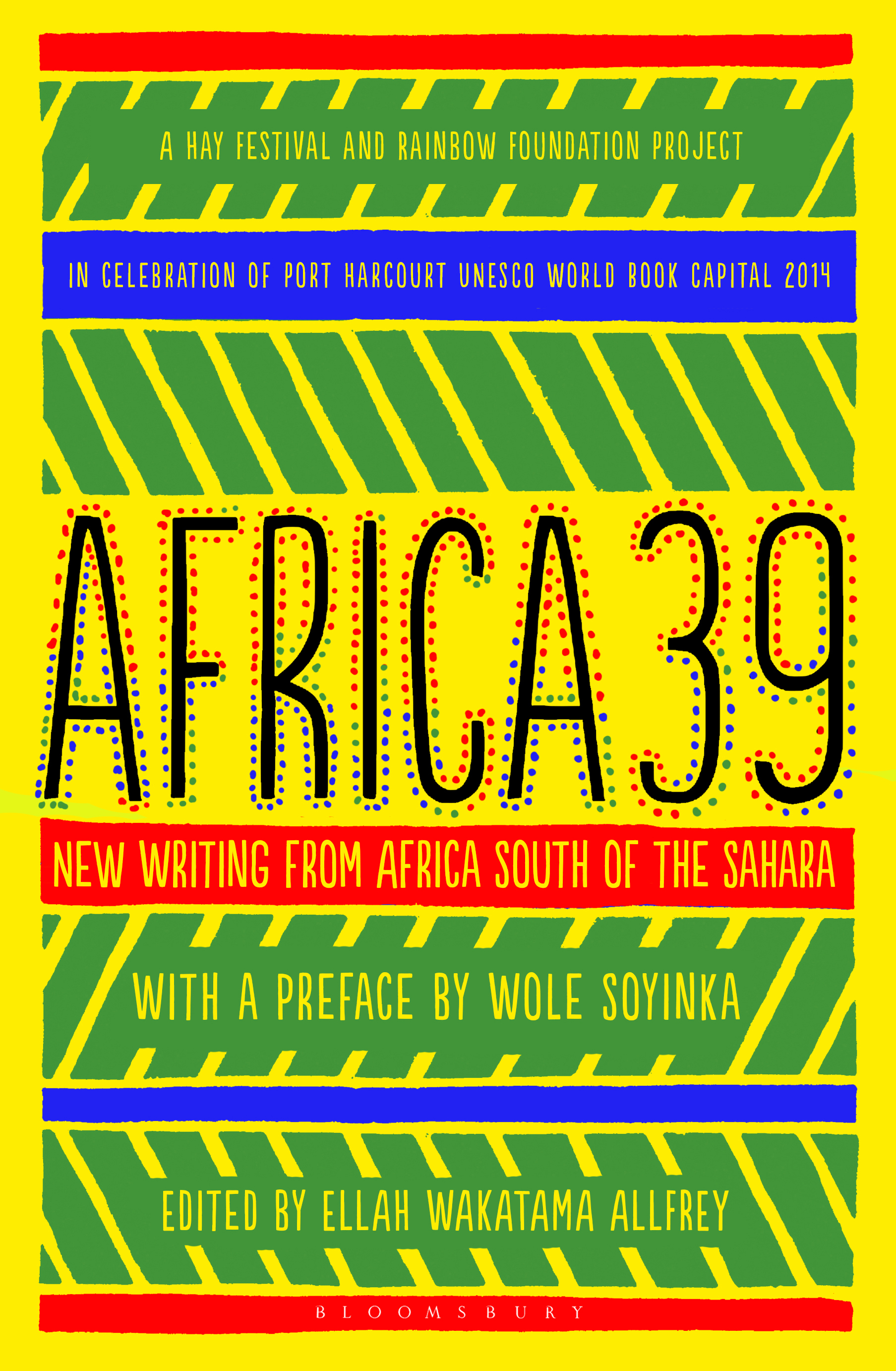

Ever since I got my hands on the Africa39: New Writing from Africa South of the Sahara anthology, I’ve been stealing a moment here or there, often on the bus to work, to drop myself into the world of one or two of the stories. I haven’t even finished it yet, because I rarely read more than one at a time, and never more than two; they’re too different, too diverse, and too radically irreconcilable with each other. This is often the way with anthologies, or collections of short stories. You get so firmly embedded in the world of one story that when you have to drop everything and reorient yourself to the next story—to give up one world and take on a new one—it takes real mental work. You get attached to the first story, and you don’t want to give it up; the new story feels strange, foreign, out of place.

To roughly shoehorn this experience into the process that Freud described in “Mourning and Melancholia,” I might say that after reading one story, I don’t want to leave it behind and read another one, because I’m still in mourning for the first story, still processing it. And when I’m reading the second one, that out-of-place sense of uneasiness comes from the fact that I am, still, in the first story: the story has changed, but I haven’t yet moved on. I look for the first story’s characters in the second story, and miss them; I try to place the second story’s characters in the world of the first story, and I don’t find it there. I get restless. My attention wanders. I lose my focus.

This is not a bad thing. This is a good thing. Freud is not the most helpful guide to a short story anthology, because loving a short story only begins when it ends, something you don’t want to try with people with love. When a short story is over, put the thing down and stare out the bus window; don’t mourn it, love it. Don’t move on. Don’t go to the next story. This is the good part! We have to mourn our dead loved ones, because they are dead and we are not. But stories don’t live or die; we read them, and we digest them.

Freud is also not a helpful guide to contemporary African literature. I say this because Mukoma wa Ngugi uses that framework in his review of the anthology for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and I respectfully disagree with a lot of what he says it to say. In his review, Beauty, Mourning, and Melancholy in Africa39, he begins with the generation of Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and writes that:

To understand the aesthetics and political distance African literature has traveled between Things Fall Apart and Africa39, one would have to think of it in those terms of mourning and melancholy, of inherited traumas and memories, which define the new African literary generation. For Freud, mourning is “the reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one's country, liberty, an ideal, and so on.” In contrast, melancholia describes when “one cannot see clearly what it is that has been lost,” and “is in some way related to an object-loss which is withdrawn from consciousness, in contradistinction to mourning, in which there is nothing about the loss that is unconscious.” The older generation in Africa can be said to be mourning — they know what they have lost, whether it is language and culture, or land and nation. And their writing is an attempt to recover a lost known object. But the Africa39 writers do not fully know the language they have lost, and have no direct memory of the land and nation that belonged to their parents. In Africa39, the characters, like their writers, have no intimate knowledge of the cultures that formed their parents and grandparents. They are in a state of melancholy.

To be blunt: I don’t see "melancholy" at all in the anthology, or at most, it’s a very minor theme.

Now, this is a very broad and dramatic claim he’s making, a sweeping generalization about thirty-nine writers under the age of forty, and it’s never going to work perfectly to describe all of them. And we shouldn’t hold it to that standard. That’s not even what a review is for. Moreover, though he’s a professor at Cornell University, Mukoma wa Ngugi is a young African writer himself, the son of Ngugi wa Thiong’o—just slightly beyond the age limit for the anthology, in fact—and a respected novelist, poet, and critic in his own right. His Nairobi Heat is sitting half-read next to my bed. But I think most of the things he says about this anthology are mostly wrong.

I do think Mukoma wa Ngugi is marking the very important shift in emphasis that this anthology very nicely represents. Chinua Achebe rests in peace and power. But the under-40 generation of African writers that make up this anthology lack Things Fall Apart as their commonly formative point of reference, and they don’t dwell on colonial dispossession in the way his review suggests they melancholically do. They read Achebe and Ngugi in school, perhaps, or about colonial history as adults, but they've read a lot of other books, too, and they still are. The past isn’t what unifies them, because almost nothing does.

I don’t want to declare this anthology to be post-postcolonial or anything, and not only because that hyphenated word makes my brain hurt. These writers can speak for themselves, and they are doing so. If you read them, you find that they say a great many different things. Some of them pass the Ngugi test: Mohamed Yunus Rafiq can remind us of Amos Tutuola, for example; Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond allegorizes Mama Africa and Rotimi Babatunde takes us back to colonizer and the colonized in fresh and strange ways. Those stories have not been lost; on the contrary, Achebe and Ngugi have been absorbed and digested. But these writers are hungry for other dishes too, and they eat their words with different palm oil than Achebe’s proverbs, washing them down with other beverages than palm wine, and carrying different traumas than the loss of the mother tongue.

This is why, if you go into this anthology with a single story about African literature—say, a story about the loss of language and culture, or land and nation, and a desire to recover those things by writing—you will find yourself chasing ghosts. You will have no idea what to do with a story like Clifton Gachagua’s “No Kissing the Dolls Unless Jimi Hendrix is Playing” (you still may not, regardless; when great poets write fiction, things get strange and wonderful). But writers like Ndinda Kioko, Mehul Gohil, Linda Musita, and Okwiri Oduor—to acknowledge that I am biased in favor of the Kenyans—aren’t really writing about what was taken from their grandparents or great grandparent: they write about the violence of the present, as well as its joys. These are new stories, and the old ones won’t help us very much in reading them.

Even the writers who were born and raised outside of Africa—people like Tope Folarin or Taiye Selasi—don’t write with the melancholy that Mukoma wa Ngugi seems to expect from them. You can think what you want about Selasi’s “Afropolitanism,” but there’s nothing melancholy about it. And while Mukoma wa Ngugi’s reading of Tope Folarin’s story—in which “we see trauma handed down to the next generation like a prized family heirloom”—is sharp and insightful, and helped me better understand what Folarin is doing with the story, he also fills his sentences with negative verbs, writing of Nigeria that “they cannot account for it,” and of their African names, “they cannot account for their names either.” I would say the opposite: all they can do is account for these things, and they do it in creative and unfaithful ways. They do not go back to their parents’ Africa, nor do they want to; they make their own roads home.

When I interviewed Tope Folarin (forthcoming at Post45), he found himself (almost apologetically) talking about “what it means to be a human in the 21st-century, when borders are collapsing.” Finding himself repeating “the same kind of Thomas Friedman point,” he hesitated—perhaps not liking the taste of Friedman on his tongue—but went forward anyway: “It’s a cliché at this point, but there’s something to it: borders are collapsing, and the net facilitates communication and that sort of thing”:

When I was in Oxford, studying for my masters, I was writing a thesis on identity, and kind of in the midst of it, I discovered that the ideas I was trying to address in the academic framework actually probably fit better in a fiction framework. Maybe in an artistic framework. Because, I was trying… My thesis, for my master’s project, was that we have the option of creating our own identities here in the 21st century, and I think that’s something our parents and grandparents didn’t have. I have the option of saying “This is who I am,” in a way my parents and grandparents didn’t have. My fiction is really interested in investigating that idea. Here’s a character who’s in this situation; what does he decide, and why does he decide what he decides?

I don’t think most of the writers in this anthology would agree about what African literature is, isn’t, or should be. But the thing I love about the anthology is how far it’s willing to walk past anywhere African literature has been before, how utterly un-representative almost every story has the courage to be. I don’t think there’s ever been a collection of stories by African writers that is quite so resolutely un-singular as this one, so impossible to summarize or describe. That’s why I think Mukoma wa Ngugi’s attempt to do so fails. But that’s not his fault: that’s the fault of the writers for straying so far from home. And because, instead of negative verbs, they packed bags and bags of question marks, as they set out on their way.