“Emerging from prison, without force of arms, he would – like Lincoln – hold his country together when it threatened to break apart. Like America’s founding fathers, he would erect a constitutional order to preserve freedom for future generations – a commitment to democracy and rule of law ratified not only by his election, but by his willingness to step down from power.” (Barack Obama, Remarks)

I.

The Nelson Mandela that Barack Obama remembers seems to have not done a great many things: he did not carry old grievances forward into the present, he did not use violence or the power of the state against those who put him and his people in open-air jails (or those who accrued vast fortunes by doing so), and he did not stay in office once he had achieved it. The mark of a great president, it would seem, is that he stops being president, that he limits his own power. A great revolutionary is someone who holds his country together.

Who is this Nelson Mandela? I know who he isn’t: George Washington, who fought a war to expel the British from his country; Abraham Lincoln, who spent at least most of his life—and possibly all of it—believing that the races could never live in harmony, together, and that part of the great abomination of slavery was that it forced an unnatural congress between them. Nelson Mandela did not own slaves; he was not a president who reconciled white brothers while leaving the inclusion of anyone else for someone else to fix; he was not white.

These facts are so obvious, they can be easy to forget. Yet Mandela is remembered and loved for not being many of the things which he also was. I don’t just mean that he is mis-remembered, though there is that, too. But if we are uncomfortable with presidents, he is a president who gave up being president; if we are uncomfortable with revolutionaries, he was a revolutionary who became the status quo. If we are uncomfortable with black militancy, he is a messiah who loved his tormenters.

“You will try to smooth him, to sandblast him, to take away his Malcolm X. You will try to hide his anger from view. Right now, you are anxiously pacing the corridors of your condos and country estates, looking for the right words, the right tributes, the right-wing tributes. You will say that Mandela was not about race. You will say that Mandela was not about politics. You will say that Mandela was about nothing but one love, you will try to reduce him to a lilting reggae tune. “Let’s get together, and feel alright.” Yes, you will do that.” (Musa Okwongo, “Mandela will never, ever be your minstrel”)

II.

By definition, violence is something that makes us uncomfortable. There are forms of violence that we are supposed to sanction, things like smart bombs, football, hunting, juridical executions, disciplinary confinement, or humanitarian interventions. But these tend to be defended or excused by appealing to their fundamentally non-violent character, or to the fact that a greater violence will, by violence, be prevented. Nuclear war against the Japanese citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for example, was supposed to prevent forms of violence which disturb us more, either because there would have been a greater number of total casualties in the invasion of Japan, or because the victims would have been of a different race than the ones we can feel sad about killing.

Debates about “violence,” in this way, are almost always confused and strange, because people tend to agree that “violence” is bad; what they disagree about is the question of what actually constitutes violence. Football is not violent (or not too violent), because it’s a game; hunting is not violent because animals aren’t human; and killing a killer is not violent because she would have killed again, or because—in killing once—all violence against her is thereafter justified (or, perhaps, does not even need to be justified).

It shouldn’t surprise anyone, therefore, that one way of eulogizing Nelson Mandela has been to praise his non-violence, to recall how he “peacefully” brought Apartheid to an end. He can be quoted as saying that “Education,” which is not a weapon, is the greatest weapon. And the easy, correct, and necessary response is to observe the erasure that this narrative performs: the founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe ("Spear of the Nation"), Nelson Mandela never disavowed violent revolution (when it was necessary) nor broke with a tradition of anti-colonial revolution—Castro, Arafat, Gaddafi, Mugabe—which saw violence as a tactic rather than a principle (albeit by reference to the real violators). As he wrote in Long Walk to Freedom,

“Nonviolent passive resistance is effective as long as your opposition adheres to the same rules as you do. But if peaceful protest is met with violence, its efficacy is at an end. For me, nonviolence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon.”

This is only a very qualified and liberal defense of violence, of course; just as liberals can go to war to end war—when there is nothing else that can be done—Mandela’s argument grants the point that non-violent passive resistance is the default until such time as it becomes impossible. At that point, the violence of resistance either becomes the responsibility of the oppressor—whose violence made it necessary—or it becomes an acceptable violence by reference to the violence which it seeks to bring to an end. When he argued at his trial, for example, that violence had become necessary, he made the point by reference to the “terrorism” which his organized violence would pre-empt:

“as a result of Government policy, violence by the African people had become inevitable, and that unless responsible leadership was given to canalise and control the feelings of our people, there would be outbreaks of terrorism which would produce an intensity of bitterness and hostility between the various races of this country which is not produced even by war.”

All well and good. Mandela was not Gandhi, but—although he went to Morocco in 1962, for military training with the Algerian National Liberation Front—the author of Long Walk to Freedom is also not Frantz Fanon, who occasionally argued the extent to which anti-colonial violence, as such, was justified, necessary, and maybe even a good thing. Mandela’s “terrorism” targeted infrastructure, not people. But he was also a bit out of step with the younger face of Black militancy in the 1970’s, and “saw it as his role to tame the new radicals”; when younger, more militant prisoners arrived at Robbin Island, in the wake of the Soweto Uprising:

“These new prisoners were ‘aggressive’, said Mandela, both in their prison behaviour and in their political outlook, and he soon realised that it ‘would not be an easy task to convert them to a more pragmatic position given their impatience with the Apartheid regime’ (8). Here, we can see, in microcosm, one of the key roles the ANC played in the 1970s: as at best an observer of huge black upheavals, and at worst the self-elected tamer of black militancy. A similar role was played by the ANC military training camps in Angola and Mozambique during this period: after the Soweto Uprising, thousands of radicalised youth went to these ill-organised camps, to be trained for a guerrilla invasion of South Africa which of course never came; the camps were effectively holding pens of militancy, keeping away from Soweto and other parts of South Africa the very youths who had so shaken the Apartheid regime.”

Still, though, it is worth saying: he wasn’t the kind of bloodthirsty warrior which the American imagination clasps so warmly to its bosom, for whom masculinity, patriarchy, and order are inextricable from (and rely upon) the joy of killing, a lust for death that far exceeds what necessity can explain. After all, alongside the apologists who use liberal arguments to deny that this particular killing is violent, there are those who simply kill and enjoy it, knowing full well that racist eyes and heartless minds will never accuse them of causing the deaths of these particular people. Thomas Friedman can advocate that Iraqis “suck on this”—by which he means that lots of people with brown skin and wrong religions need to die so that Americans can feel better about their virility, and that’s okay—because so many of the Americanns who read him are actually somewhat okay with violence, as such, as long as we are doing it to them. And when it comes to the men who made us a “we”—our warrior founder fathers—all bets are off; “We laud our founding fathers for their deep commitment to non-violence in the face of tyranny,” as as Matt Stoller observed; “The Star-Spangled Banner commemorates the great American nonviolent march of 1812 when an accidental fire burned down the White House.”

"I won't speak until there is pindrop silence," says Desmond Tutu. "You must show the world you are disciplined. I want to hear a pin drop." (Desmond Tutu, at Nelson Mandela’s memorial)

III.

In Achmat Dangor’s wonderful and painful 2004 novel, Bitter Fruit, there’s a scene near the end of the book that has been stuck in the back of my mind ever since Mandela passed away, a moment in which a lost youth, wandering alone in the dark night, is offered a ride by President Mandela. He declines.

The shock of that moment is two-fold: Mandela is a myth, an impossible fantasy of the father of his nation, and as such, he can’t really exist, can he? We are as surprised as is the young man, Mikey, to see this figure of myth and legend, drive out of the darkness in a high end luxury car. He can’t really be a real person (can he?), offering a lost stranger a ride… myths don’t do that. Stories and reality stay distinct from each other. Which is why novels don’t often have Nelson Mandela as a character, even so fleetingly as this. One of the novel’s main characters works for Mandela—and early on, is asked what the president is really like—but we don’t expect to see the great man on the pages of the novel, a work of fiction imagined around imaginary people who never existed. The eruption of the real, in that moment, is poignant and unsettling: one never expected him to be real, and yet there he was, there he is. And because he is there, in the flesh, something happens to the myth, to the legend, something irrevocable.

Along with the possibility of the impossible, as the myth become real before our eyes, this moment also marks its failure as reality. The story of Mandela is a powerful story, but the reality is disappointing, and must be. He’s just a VIP in a Mercedes, unable to know or help. He can’t give the young man a ride, and not only because the young man can’t accept it, and won’t accept it; what are great men good for, other than dying famous deaths? The young man walking in the night, is uncomfortably aware of the gun in his pocket, and though it stays there, “terrorism” is the word his mind doesn’t quite form but also the story which the novel can’t help but tell, as overdetermined as “Mandela.”

Bitter Fruit is set in the late 1990’s, about the end of Apartheid, but because it recognizes that not all trauma and guilt can be healed and forgotten by telling stories, by witnessing—because it remembers that reconciliation is gendered, that silence can be inscribed on the bodies of women—it’s about the disciplinary violence that we find in the forced stories of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, about what was lost and obscured when private trauma was translated—and had to be—into national mythology, and about how the process of reconciliation through truth could demand the fiction that the past had passed. If Mandela’s story was inspiring, it was also compelling, making demands on the bodies of those who suffered, who would be allowed to remember only in order to forget. For Mikey, the young man in the dark, “Mandela” is a name, a story, and a country with which he can have nothing to do, a country that cannot include him: he is the novel’s “bitter fruit,” the result of his mother’s rape by a white policeman, but that origin is not a thing which he, his mother, or his father, can ever have the luxury of forgetting. And to demand forgiveness as the price of admission to the New South Africa is to expel those who had none to give; to imagine that the crimes of Apartheid could be forgiven, forgotten, or transcended—and to enforce and rehearse that imagined community with all the moral authority of a national myth—was to make outsiders of those for whom the past could not so simply be sloughed off and left behind, to make insiders of those for whom it could.

“An alien visitor to our media environment this week might notice two things. One: torturers and their assistants expressing how profoundly they forgive themselves. They love television, and they love newspapers, and their memories of what they did in the nineteen-eighties, what crimes they participated in or supported, are foggy. In fact, often, there is nothing to forgive. Everyone was on the side of the angels. A second phenomenon, related to the first: torturers expressing their disappointment in the tortured. What is the matter with these blacks? The tortured act troubled, it is observed.” (Teju Cole, “Reconciliation”)

IV.

Is Nelson Mandela to be remembered for his peaceful spirit of reconciliation or as the “George Washington” of South Africa, or its “Abraham Lincoln”? Both of these narratives are wish-fulfillment fantasies. Mandela was closer to a “by any means necessary” type of revolutionary than a Gandhi, but Lincolns and Washingtons were more like F.W. de Klerk, a statesman who found himself belatedly on the right side of history, and deserving only some of the credit for getting there. If Frederick Douglass had become an American president, perhaps then we’d have a figure we could meaningfully compare to Mandela. But how many freedom fighters ever become president? When an American claims that Mandela was a Washington or Lincoln, what we really mean is that we wish (or believe) that our founding fathers had half the nobility of spirit as South Africa’s founding father. We wish and hope that our presidents would have the power to change an unjust system, rather than come to embody it, especially since our current president so clearly marks the gap between Hope and Change.

Still, people like Washington and Lincoln cannot be and are not figures for emulation, and not only because they lived in fundamentally different times. They were not defined by their times, but fractured by them—as all of us are—torn in opposing directions by irreconcilable pressures and needs. The interesting thing about someone like Thomas Jefferson, after all, was his failure to reconcile enlightenment idealist theory with practical white supremacism, and his struggle to do so. And if Lincoln was a remarkable human being, I would humbly suggest that we can better understand our contemporary predicament if we think about how slowly, how belatedly, and how reluctantly he came to embrace the emancipation of black slaves. Both were “against slavery” in an abstract sense, and believed the peculiar institution to be doomed in the long run, but, in practice, they managed to find a great many reasons why the time was not yet ripe to actually do something about it, not yet, not now.

This might be the thing that makes Mandela truly worth honoring: no, he said, we will do this now.

This, however, is not what politicians would like to remember Mandela for being. When John Kerry invoked Mandela’s name the other day, at the end of a speech on the “two-state solution,” the Mandela he invoked was not the guy with his arms around Yasser Arafat, who Mandela called “one of the outstanding freedom fighters of this generation.” Kerry was imagining a fantasy Mandela, who “was a stranger to hate,” who “rejected recrimination in favor of reconciliation, and [who] knew the future demands that we move beyond the past.”

Obviously, this is not the Mandela who organized a militant wing of the ANC to blow up power plants; this is the Mandela who, once Apartheid had been abolished, chose to reconcile with South Africa’s white minority, rather than dwell on “the past.” This is the Mandela whose government chose to honor the debts to the world bank’s development funds, which the Apartheid state had accrued in building and repairing those very same power plants and electrical stations; “the Bank’s US$100 million in loans to Eskom from 1951-67,” which, as Patrick Bond notes, “provided only white people with electric power, but all South Africans paid the bill.”

“What did Dick Cheney mean when he said Mandela had mellowed? Nelson Mandela initially advocated the Freedom Charter as a means to end economic apartheid.The Freedom Charter stated that, “the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and the monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole . . .” This was completely unacceptable to the white establishment. They wanted to keep the minerals and all else they had forcibly taken from black South Africans.The moment Mandela agreed to renounce all claims to economic justice he immediately became a good boy in the eyes of white capital. This is what Dick Cheney meant when he said Mandela had mellowed.” (Amai Jukwa and Garikai Chengu, “A Strange Love for Mandela”)

V.

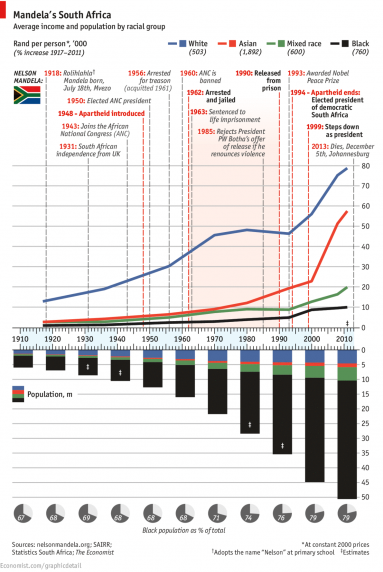

When we praise the great heart which enabled Mandela to refrain from punishing white South Africans—even by dispossessing them of land and capital which had been literally and violently taken from non-white African people—we do not tend to remember that the property of loyalists was confiscated after the American revolution, or that this accumulation-by-dispossession helped the American state jump-start the process of building its own industries. And yet the land and capital which our founding fathers appropriated was far less ill-gotten, even by their standards, than the vast wealth produced in the industries and mines of South Africa under apartheid; the loyalists were just British-Americans who made the mistake of backing the wrong horse, and paid a price that was just as arbitrary. When the ANC declined to make concrete and material reparations for past crimes and dispossessions, offering South Africans a reconciliation by “truth” instead of by justice, he left the economic foundation of white rule in place, giving the black masses very little with which to close the gap. The results are predictable.

But, of course, the American revolution is not a model for anti-colonial revolutionaries to follow, is it? They are to be praised when they love and forgive their oppressors, when they are content to wipe the slate clean for everyone. As Amai Jukwa and Garikai Chengu bitterly observe,

“Earlier this year Hans Lipschis, a 93-year-old former Nazi guard, was arrested in southern Germany. Why don’t the Europeans do the very thing they are praising Mandela for and forgive this Nazi who is elderly and frail?”

If we praise Mandela’s forgiveness, or if we endorse hunting down elderly war criminals, there is no principled consistency to be found in doing both: there is only the reality that crimes are criminalized differently, depending on who the perpetrator is, and who the victims are. Some debts get forgiven; some do not. When Toussaint L’Ouverture led a revolution in Haiti against the French plantation capital that made slave labor its mode of production, his fledgling nation achieved independence with the sword but kept it—or kept something to which the name was given—only by assuming a massive debt to France, compensation for their loss of colony and slaves. Haitians used violence to force the French to become “willing sellers,” in other words, but that nation’s inability to pay off the debt it assumed—for centuries—has condemned that nation to a different kind of (neo)slavery. If one follows W.E.B. Dubois in reading the emancipation of American slaves as being the result of a slave uprising—which both provoked the civil war itself and was enabled to succeed by it—then we can observe that blacks could become free, but could not demand compensation for their enslavement and were, instead, ushered into new forms of debt servitude. Here, too, the debt was assumed by the victor of the freedom struggle, who still needed to buy her way to freedom.

This is what it means to praise Nelson Mandela and his government’s choice to assume a “willing buyer, willing seller” approach to land reform, as well as his government’s “choice” both to borrow from the International Monetary Fund—accepting the variety of conditions which such loans brought—and to honor the various Apartheid-era debts which a whites-only government took out, for the benefit of whites-only—but which a multi-racial nation would find itself paying off, pretty much in perpetuity.

Patrick Bond has the details, but the important thing is the big picture: instead of using ill-gotten wealth to repair some of the damage which they had done, white South Africans and world capital were willing to do no more than wipe part of the slate clean, allowing the formerly oppressed the privilege only of buying back some of what had been taken from them. Perhaps freedom is acceptable when it has a market value? But the debts which the white supremacist state had racked up, were to be paid off by the non-white populations whose parents suffered from it, who are born into a different kind of poverty than their parents, perhaps, but which nevertheless bears some striking resemblances.

I am always astounded by the persistent references in Zimbabwe's The Herald newspaper together with its sister publications to former president Nelson Mandela as simply nothing more than what the African Americans call Uncle Tom or house nigger. (Vusi Mavimbela, “Why Zimbabwe's Herald is wrong about Mandela”)

VI.

It is easy to pin the blame on Mandela. It is easy to invert the messiah narrative, and make Mandela the traitor who gladly accepted the West’s adoration and sold his heritage for a mess of pottage, his radical allies for 30 pieces of silver. It is easy to call him an Uncle Tom.

But the “Uncle Tom” figure only ever existed in the feverish imagination of racist white minds: to pretend that it means something—that such a person truly exists or existed—is both to credit a fundamentally racist fantasy with a truth it does not possess and to participate in its propagation. “Uncle Tom” is a fantasy; it is what antebellum white Americans needed to imagine and speak into existence if they could bear to imagine the possibility of an end to black slavery. The sticking point for Thomas Jefferson, after all, was the possibility that freed slaves would choose to take vengeance on their former masters, emulate his own declaration of revolutionary independence, precisely because he found it hard to deny that they would be right to do so. How could he argue that “the slave may not as justifiably take a little from one, who has taken all from him, as he may slay one who would slay him?” For Jefferson, then, the (white) United States had the wolf by the ears, and there was nothing that could be done to bring about a multiracial society; the only solution was to keep them in chains or send them away to Africa.

“Uncle Tom” solves this problem, because it fantasizes the slave who will forgive his master for the violations which were done to him, indeed, who will love him all the more for it, as Tom loves, forgives, and prays for Simon Legree, even as he is being beaten to death. It was because he was necessary that Harriet Beecher Stowe imagined into existence a slave who could emulate Jesus, forgiving even those who enslaved him, and loving them precisely because they didn’t deserve it. Such a slave could be loved, and even freed. But all the others had to be either kept in slavery or colonized back to Africa. This dream, this wish-fulfillment, was part of what made Stowe’s novel one of the most successful narratives of the 19th century: Thomas Jefferson could not reconcile his sense of justice and self-preservation; to give justice to his slaves, he allowed himself to believe, would be to be destroyed. But Stowe could succeed where Jefferson failed, because she could imagine the abolition of slavery through the Christian forgiveness given to the crucifiers by those who had crucified him.

Nelson Mandela has been called an “Uncle Tom” many, many times, though he’s been defended from that epithet at least as many times. It’s a waste of breath to observe that he was not an Uncle Tom, because no one ever was, but it’s good to say it, anyway (and you can find many more vigorous defenses from the charge than you can find polemics accusing him of it). “Uncle Tom” is a piece of minstrel theater, and Nelson Mandela was not a minstrel. But no one was, and that’s just as important: the conceit of that word is that a slave has a choice, and that there is a right and a wrong choice, the difference between the noble field slave and the corrupted house slave. But it’s all a grotesque category error: to have a choice is to be free and to be a slave is not to have a choice, and if we forget that simple distinction, we will very basically misunderstand what we are talking about. This seems to me to be exactly the point: if we can imagine the slave who chooses to be a slave, then, who chooses to love his master, we can also imagine the opposite, the slave who chooses to be free. In that instant we take credit for our own freedom, imagining that we chose rightly. But just as no one ever made themselves free by choosing it, no one ever made themselves a slave by choice. Uncle Tom will never be your minstrel either.

Nelson Mandela sold out black South Africans. Now there's a sentence you won't have heard in the days since his death and that you won't be hearing at his memorial tomorrow. Yet it’s incontrovertibly true that after centuries of being robbed of possibly the greatest mineral wealth the world has ever known, not to mention decades of being repressed by apartheid, black South Africans got almost no compensation for what should rightfully have been theirs when the old regime was swept away for the new South Africa.Indeed, the basic deal Mandela struck from prison with F.W. de Klerk, and which was subsequently enshrined in the South African constitution, essentially guaranteed the existing property rights of white South Africans in exchange for an end to apartheid. (Noah Feldman, “Was Mandela Right to Sell Out Black South Africans?”)

VII.

It is not hard to accuse Mandela of selling out the freedom struggle. It is simply a historical fact that the terms on which Mandela bought the end of Apartheid were far from what they had previously declared they would accept; the Freedom Charter demanded that South Africa’s massive mineral wealth be nationalized, and it was not, in fact, nationalized. Let that enormous failing stand in for the many other compromises, trade-offs, and deals which were struck, for there were many: Mandela the president did many things which Mandela the revolutionary would not have done. The presidential Mandela was very different than “the radical Mandela, who had endorsed Marxism back in the 1950s,” as Patrick Bond remembers:

“the Freedom Charter of 1955 called for the expropriation of the mines and banks and monopoly capital and their sharing for the people as a whole--. When Mandela came out of prison in 1990, he said, that is the policy of the ANC and a change in that policy is inconceivable. But it was only a few months later before--I certainly witnessed that in Johannesburg in that transition period, 1990 to '94--major compromises were made with big business. And big business basically said, we will get out of our relationship with the Afrikaner rulers if you let us keep, basically, our wealth intact and indeed to take the wealth abroad. And so exchange controls were relaxed very soon after Mandela took over.”

Under Mandela, as the September National Imbizo put it, “political power was not to be used to address the injustices of the past”:

“Instead, Madiba elevated the flawed notion of peace to a virtue. Madiba was celebrated, but the people remained landless, poor and assaulted by white racism on a daily basis...The tragedy was always how our people yearned for Madiba to be a hero that ended their squalid conditions instead of preaching peace at the cost of redress. The consequence is that our society has neither peace, justice nor a sense of genuine unity. We are a nation of sport events unity.”

Or read Ronnie Kasrills. Or so very many other South Africans, who have the burden of living with the consequences, who cannot enjoy imagining the freedom struggle as a nice story, to be gratefully consumed like Invictus on Netflix. But maybe this is always the way; maybe revolutionary-presidents are always disappointing because the job descriptions are different. Revolutionaries can promise, but heads of state must lie: a revolutionary can pin transcendence to the horizon of futurity represented by the Revolution—putting off until tomorrow what cannot be done today—but the president must reconcile the contradictions of sovereignty through deceit. What she cannot do, she must pretend to be doing; what the nation cannot be, or what it cannot help but be, the state must erect fantasies to obscure.

South Africa was never free, least of all when the end of the cold war cut the legs out from under the Apartheid state and brought the freedom struggle to an end. With the fall of the Soviet Union, there was no longer a reason for the US to pay the costs of sustaining the Apartheid regime, so we stopped, and so did they. A compromised devolution was inevitable, and it came. It would be nice to believe that someone like Mandela could make history as he chose, that his will, principle, and character could force history to bend according to the arc of justice. But it was also as simple as the fact that Apartheid ended because the world to which it belonged had come to an end; with the loss of its necessary—if not sufficient—cause, a change was inevitable, and it came. Decades of struggle might have prepared the ANC to pluck that fruit (even if the devil would survive in the details), but that tree of liberty was watered with the blood of many patriots; as Zachary Levenson reminds us:

"it was the Pan-African Congress that played the central part in the early 1960s struggles after Sharpeville, and it was Black Consciousness militants and unaffiliated students who rose up in Soweto in 1976; the ANC only claims credit for both uprisings in revisionist accounts. And neither the civic associations nor the unions that played such a decisive role in bringing down the National Party were initially aligned with the ANC. The point is – and this can’t be said often or loudly enough – Mandela and the ANC did not bring down the apartheid regime. A thirty-year cycle of struggle by community organizations, students, unions, and independent workers secured victory."

Anyway, it's a human conceit to pretend that we are not the playthings of history, to imagine history as a stage on which great men declaim, instead of a shifting morass of unknown causes and unexpected outcome.

Sometimes things have to change if they are going to stay the same, and despite everything that changed when Apartheid ended—and it does us no good to underestimate what a momentous change that was—some things have stayed the same. Even decolonization could be, in practice, a means of maintaining the colonial status quo in a different form: the bargain that was offered and struck, across decolonizing Africa, was to let white supremacy end as long as property rights and capitalist continuity were insured. White governors would depart, but white landlords would remain. Something similar has been true with Apartheid; the president is black, but those who own the mines still rule.

“He no longer belongs to us; he belongs to the ages. Through his fierce dignity and unbending will to sacrifice his own freedom for the freedom of others, Madiba transformed South Africa and moved all of us. His journey from a prisoner to a president embodied the promise that human beings and countries can change for the better.” (Barack Obama, Remarks)

VIII.

For a long time, “apartheid” was the word which pan-Africanists used to name the gap between hope and change, in the wake of decolonization, to measure the distance there was still left to go on the long walk to freedom. Much of Africa had decolonized by 1970, but Southern Africa had not, and Pretoria and Washington would fight a long and protracted and very hot version of the cold war with Havana and Moscow, in Rhodesia, Mozambique, Angola, and in South Africa itself. Israel, which had at one-time been a strong ally of the various anti-colonial resistance movements in Africa, became the apartheid state’s military contractor, and the US would work to undermine black sovereignty anywhere it might threaten South African “security.” And so, until Apartheid ended, there was still a wind of change blowing through the continent, still a spark of revolution. Mandela was still there, waiting, a contemporary of men like Kenyatta, Nkrumah, Lumumba, but one that had not been compromised or killed. When Apartheid ended, so did this Mandela; revolutionary became president. Icon of the freedom charter became “diamond shill.” Things changed, so business could continue as usual.

If you’re a president, it probably feels good to think about this, about how a revolutionary came to defend the stability of the society he once threatened to overturn. It probably also feels good to think of him as historical, as past: like Nkrumah or Lumumba, he is no longer our problem, no longer our responsibility. Instead of a defiant refusal to stop short of victory and a refusal to compromise or negotiate on principles, he can represent the passing away of that very thing. There was no compromise with Apartheid, of course, but when it comes to a word like "Marikana," and the problem of the “the moneyed, educated class of white people who [are] integral to the economy”—as Jelani Cobb curiously describes Apartheid’s shareholders—we suddenly find ourselves on the terrain of “job-creators” and dependent labor, a state of permanent inequality beyond which we cannot hope to move, and shouldn't try, and governments that act as a mercenary army for capital. We are left with the words of the revolutionary who became president, in 1995, reluctantly but firmly surrendering: “The government literally does not have the money to meet the demands that are being advanced," he said; "Mass action of any kind will not create resources that the government does not have and would only serve to subvert the capacity of government to serve the people.” This Mandela, I think, can be left to rest in peace.