Inhibitions are like the bones in a creature. You pull all the bones out and you get a floppy jelly.

- Nigel Kneale

At the start of the program, which is in black and white, there are feet and limbs, thick with chiaroscuro. A thigh in foreground is a landscape feature, a grainy massif. It looks dusted with fine powder, with snow, with ash.

Watching this, I think of Hiroshima Mon Amour, the entangled bodies covered with that radioactive ash 9 years prior.

But this camera keeps moving up, to show that the embracing bodies aren’t naked but adorned, and oddly so, a tangle of metallic braiding, straps, indistinct tufts. We appear to be less in the realm of meditations on how memory torques in the face of genocide, more in a Kansas country fair staging of Caligula. And the camera keeps moving further, up to the arms and the wigs and the faces of those bodies and then, cutting, to other couples as well, all mouths locked to each other, pivoting slightly, the muscular hairless arms of men at angles and crooks to hold those men poised over a woman, to keep her head in place for the slow necking.

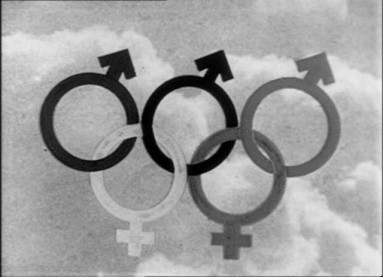

On the faces, rhinestones have been glued to cheeks, crystals stuck beneath eyebrows to double them. The country fair has gone vaguely futurist, though not Afro in the least: all the participants are decidedly white, as will be literally every person to appear in the drama’s duration. Long blond hair tactfully covers the breasts of one woman. Glimpses of portions of columns behind and amongst them fleshes out the Athenian idyll of this low-grade orgy, until a distinctly British voice booms out to inform them “that does it for the warm up,” because the fictional television program (SPORTSEX, in the future, “sooner than you think…”, an opening intertitle announces) about which this actual TV play (The Year of the Sex Olympics, from here out, The Sex Olympics, 1968, written by Nigel Kneale for BBC) will focus is to begin shortly, at which point the hard bodies will go wholly hardcore.

We, the viewers of The Sex Olympics, won’t ever get to see that, although we’ll hear a little panting and a lot of talk about it, its quality and efficacy, its intended purpose: a sexual competition, scored by judges, with point tallies counting toward the “Sex Olympics." All, however, with the end not of arousing viewers, as pornography might and can, but the very opposite, to appear so technically impressive as to instill in the audience the sense that, as its programmer puts it, “I cannot do like that… not even try. Sex is not to do. Sex is to watch. That’s what they gotta feel.” Apathy control, it’ll be called, with the intent to discourage those designated “low drive” to stop reproducing and contributing to the catastrophic world overpopulation. In other words, population control by activating the erotic sublime, such that a wedge of technique - composed of polished surfaces, careful orifices, a few handfuls of sticky glitter, and machinically precise rotations - is driven between sex as aesthetic experience and as practical experience. The mind reels, and, in a self-annihilating moment of comparison, the libido goes kaputt.

Fair, and clever, enough. But one might expect the audience reaction to be closer to that of most committed sports fans who watch athletes doing activities with a skill they could never remotely match: yelling, massive emotional investment in the contest’s outcome, endless critique of the skills of the players or referees, dizzying bodies of statistical knowledge, an occasional riot, genuine joy, fantasy leagues, and a tremendous amount of barely rerouted homosociality. In short, with the same end result of not going out and doing the very activity witnessed, but through excess investment in it, rather than heights of spectatorial dispassion. However, one could contend, that’s more the case with team sports, when the collective experience of watching finds an echo in the game, while the “sportsex” on display here stays closer to pairs ice-dancing, with the addition of a bodily fluid or three. And as far as memory serves, there has never been a riot following an ice-dancing victory or loss.

Perhaps sadly, the BBC was unwilling to test this theory of rapt apathy on its own audiences, so we don’t actually see the gleaming, grinning, toothy lovers do what they’re there to do, even if we’re assured that they’re “superking” (the preferred superlative of this future), including the recent winners of "the Kama Sutra prize." Instead, in an apt doubling of the program’s critique of television’s expected passivity, we watch watching itself. Specifically, we watch the watchers as split in two groups, “high drive” and “low drive.”

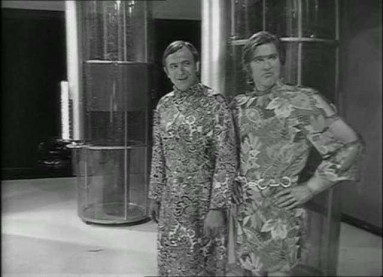

Behind the camera, the host and programmers, all high drives, the hierarchical upper crust, who divide their time between managing this post-culture industry and engaging in serial trysts, aided by video backdrops (the Arctic, the cosmos, a volcano) and a giant spinning furry tickler.

They breed only with each other but don’t form family units, placing the occasional offspring of their couplings into the regulatory hands of the state, if it’s indeed a state in the contemporary sense of the word. The women are blond pseudo-Barbarellas, all exposed flesh, long legs, glitter, and jitters, while the men are fragments of ‘60s psychedelia gone worse, sporting hideous patterned tunics, ponytails, sideburns, and even more jitters. All use a sort of collapsed version of English, choppy and staccato, with missing conjunctions and articles, as if to indicate - as in 1984, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, Raw Meat, Idiocracy, general fears about emoticons and SMS-speak, et cetera - the loss of traditions of linguistic continuity and mass rationality. They calibrate the show, speed it up when necessary, bemoan the scarcity of “good talent” these days, and, above all, watch the other watchers, the test audience, checking that they’re properly apathetic.

That audience is culled from the low drives, although whether or not they are the global sample or just a segment of the apparently all-white British slab, we won’t know. We can’t say because we remain wholly in the dark as to just how global this technique of population management actually is, whether or not there is a unified para-state organization to handle the world distribution of depressingly impressive sex, and to where the non-white population of the UK has disappeared. (In a 2003 interview, Kneale suggests the UN as the imagined model of this organization, at least of . “I imagined a world that had a policy through the UN to show as much pornography as possible. The aim would be to keep people happy and not let them build up any tension. Things like wars would be finished – they would never happen again because people would be too busy chasing each other. It seemed to me to be an entirely probable situation.”) Given the actual trajectory of population growth rates in the global north from the late ‘60s on, if The Sex Olympics is any way prescient, as later critical celebrations of it will claim, it surely isn’t about the imagined social source that necessitates SPORTSEX, the excess birth crisis of a continually swelling population of the British and continental European white unemployed, working, and middle class.

Nevertheless, the rough implication is that the low drives, of which these are an evidently representative sample, comprise the majority of the world’s population, a sort of species-wide decadence without either Lovecraft’s degradation (into “sub-human” physicality and other species traits locked within, as in Quatermass and the Pit) or Nordau’s degeneration (Entartung, involving the “illness” of decadence and the social imitation of “degenerate art”). Instead, it’s just an accelerated greying out, with ever-falling life expectancy (around 35 years, most of which are spent watching TV) and the gathering exhaustion of those who “just sit and watch.”

The reinforcement of this split as biological, rather than socially produced, is the central problem on which the plot will turn, through the possibility that the child, Keten, of two High Drives, Sportsex programmer Nat Mender (Tony Vogel) and Deanie Webb (Suzanne Neve), one of his ex-partners, may in fact be low drive and would therefore be sent “out there.” At the center of its narrative urge, then, is the problem of inconstant and resistant materials at odds with their intended purpose, through the figure of a genetically hardwired failure to be productive or an insistence on the right to be lazy, depending on how one reads the low drives. But we know little more than what we see in how they appear to us on the screen: passive, haggard, slack-jawed, and, as the show’s squealing presenter Misch (Vickery Turner) puts it, “sticky”. Not sweating or hot, no, “just their own stick then. Yeeewwwck.”

In another filmed work that Kneale wrote, Quatermass 2, a man is coated, head to toe, with a rather different “stick,” with what’s alleged to be synthetic food. But it burns and kills, as though it were a toxic sludge, like the muck that poured from the Ajka aluminum plant in Hungary 2 years ago and the biosolids of human waste dumped in seas and rivers: the poisonous remainder of a process directed toward the production of something other than the sludge itself, whether that be metal or human life. However, in Quatermass 2, this is no excess, no slag. It’s the product itself, the mass manufacture of what will destroy its makers, to pave the way for the invading aliens directing the process.

That moment of revelation - it is not food, it burns us, and yet we labor to make it - coupled with its visual counterpart, the man tarred and smearing, is a central one in Kneale’s work. In certain cases, it makes little sense to put such techniques under the sign of an author’s name, but here it does, as it’s a recurring move or operation throughout his scripts, hitting its fever pitch in Quatermass and the Pit’s nasty shock of involuted species being, where it’s revealed that we humans are already the aliens who may come to destroy us all, our own latent invading force. The human itself becomes the hostis humani generis, the enemy of all humankind.

This move is a double one. First, the revelation of what has long been the case, hidden right under our noses and within our towns, subways, walls, flesh, and deep genetic memory. Second, the insistence of that revelation as material and already present: not a haunting divorced from that material, not an invasion (i.e. the input of new phenomena) but the consequence of a substantial and ongoing presence, as well as its accompanying reek, fire, howl, or poison. This is the core of the peculiar materialism of Kneale.

Why “peculiar”? I don’t mean “weird,” although the current vogue for that word folds in a few aspects of Kneale’s work, above all their short-circuited and compressed interaction between timescales (quotidian and deep cosmic) or spaces (quaint British countryside and Martian war zone) brought violently together. However, the word “peculiar” has its roots in the sense of property, specifically private property (peculiaris), and it hints both at a system of property relations in general (by which any object, being, concept, or duration of time can be owned) and the “properties” materially specific to and inseparable from such potentially ownable things. To speak of something as peculiar in these terms, then, is to see them as caught in, and given shape by, the ultimate incompatibility of these two senses of property, between something peculiar to an individual (i.e. ownable) and what is peculiar about that thing, its qualities that may be at full odds with what its owner might expect or like it to do. But this isn’t an ontology or claim about the general status of objects in the least. Rather, it’s an emphasis, an inflection, and a method of looking, one that specifically concerns intersections between social structures and the materials used by, and against, them.

Kneale’s work is one that turns on this emphasis, although it gives it a more specific form: namely, the fraught relation between the banal

However, this tension is a formal one, without determinate content. It therefore could be worked out in more than one way. A historically grounded analysis of commodity structure and circulation, for instance. For Kneale, though, its elaboration will be guided and grounded again and again by the generic, using the mechanisms of cultural genres, specifically the overlapping techniques of horror and sci-fi, to marshal certain kind of materials and affects, constrain them to work in distinct ways, and, crucially, place the banal “surrounding” materials (all the aspects that don’t immediately scream out “horror” or “sci-fi”) as always potentially under their sign, always almost alien or hostile. More basically, in terms of “what happens” in his works: in scenarios inherited from the pages of pulp, the fully banal sphere of tense yet functional civil society gets pierced, infiltrated, and corrupted by what appears first as alien to it and second as already there from the get-go.

The point of trying to isolate this peculiar materialism is to suggest that much of what drives Kneale’s narratives, as well as making them perennially disquieting, is a tension they establish not between opposing forces but internal to a relation itself, as what could be owned, managed, or utilized also proves itself incapable of being fully restricted, controlled, or explained by its owners. In this way, it points toward a fleeting but nonetheless potent moment of doubt within the structures of capitalism: materials, no matter how aligned to the order of value and property that conditions and generates then, might for that very reason contain within them aspects that escape detection and that remain capable of betraying themselves.

In other words, in relentlessly giving a material (stone, sludge, glitter, stickiness, genetic predisposition) to the abstract and malicious, especially in terms of what seems to temporally escape or exceed its bonds and falsely appear “spectral,” Kneale’s work offers an occasion to think better about what makes capital relentlessly renew itself as a relation of abstract equivocation of value between incommensurate materials, heaps of waste be damned. And insofar as those materials involve not just things like “sludge”, “information technologies” and “houses” but also “human beings,” as they do in Kneale’s work (“low drives,” to take one example), things get more a lot nastier and more interesting.

However, perhaps in favor of laying the stress on the alien side of the equation and devoting much speculation to how “they” work and what their plans might be, more serious reflection on the mechanisms that underpin “the banal” will be markedly absent. Given this, as well as the massively conservative bent that can’t be put to the side, any claims to some radical kernel within his work should be taken with many, many grains of salt, if not dismissed. Consider, for instance, that vision of a white Britain (in which more quotidian “aliens,” such as those from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Jamaica, Kenya, and so on will almost never appear, and not just in The Sex Olympics); its recurrent narrative centering on middle-aged white males, thereby framing its experiences with the limits of thought and the fantastic through such men as the general subject of experience; and its intensely anti-Irish perspective (see Halloween 3: Season of the Witch for any doubts on this). Moreover, as should be clear, speaking of “materialism” here is distanced from its more important meaning, namely, as a method that thinks the historical determinations and processes by which the apparently ahistorical comes to be or be inflected.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p8xjJl6M-Sg

In other words, reflections on a problem of matter aside, Kneale is still no Joris Ivens and shouldn’t be constructed that way. This reference isn’t as arbitrary as may seem: take, for instance, Iven’s documentary The New Earth (1933), in which the process of dragging forth fertile mud and muck from the North Sea and creating agricultural land in an inlet, with the process extensively detailed, gives a material and materialist grounding for the subsequent and brutal revelation that the grain grown will not be eaten but be left to rot or burned in order to keep the global price of wheat high. The minutely detailed and explanatory emphasis on the means of this process and the sudden evacuation of their supposed end - the noble effort of aiding the hungry collapsing into a vicious rationale beholden to a different order of valuation - is certainly familiar to Kneale’s production, not least because of the fondness for infodump explanations. But as is obvious, the social concerns in the Kneale works will be present only as details of texture (settings, accents, clothing, scars) and as the structure of material revelation detailed earlier, because the topic itself will be elaborated in terms of the generically horrific. We’ll go from “the food will be burned” to “the food, my God, it burns!”.

For a certain cherished mode of analysis, this focus on the obviously generic would appear as a set of transpositions, staying far afield of certain mid-century British tendencies toward Angry Young Men and the working class with its warts, kitchen sinks, and all, to dwell instead with various Yeti, witches, Reasonable Older Men On The Wrong Side of History, evil Irish entrepreneurs selling explosive Halloween masks, sonic haunting, and, above all, aliens, again and again and again. To this kind of reading, committed to locating an allegorical function as a way to access the historical particularity of these works, each transposition constitutes an istance of political dream work, a simultaneously fantastic and dour mirror of the nation in which horned extraterrestial insects stand in for a colonial imaginary gone very wrong.

But that ultimately misses the more relevant point, namely, how the undergirding tension between the banal and the alien will take on, in the majority of the instances, the related problem of how matter and memory intersect. Or, more precisely as it figures in his scripts, their unification into material memory.

The echo of Bergson is incidental, arriving more from the fact that to say that Kneale is concerned with matter and history simply wouldn’t be true: like the devil, in Kneale’s work history is in the details, to be excavated only later by, for instance, artists such as Patrick Keiller, whose Humphrey Jennings-inspired method will place Quatermass 2 back in its site, approaching its missing history through the circuits of landscape itself. But barring those operations, history - as an aggregate of determining processes that can't be separated from the attempts of peoples to understand and inflect them - isn't properly a concern in these works. Memory, however, will be and obsessively so, particularly as distanced from an individual's memories and especially in a prefiguration of the more recently acquired meaning of that word: the capacity of hardware to contain something other than itself, specifically data. So as most of Kneale's major sci-fi is set not in the future but in its present, that present will be invaded by memories of other times reactivated by the inadvertent hardware of the present, a set of unlikely mnemotechnics: stones that replay a past death (The Stone Tape), mass death in the future beamed back in time (The Road), mass death of another species in the past replayed in the present to presage the coming future genocide of this species (Quatermass and the Pit).

What, then, of The Sex Olympics itself? At first glimpse, it's significantly different. Like The Big, Big Giggle (an unfilmed Kneale tale of teenage copycat suicides deemed too likely to induce actual teen copycat suicides), and the 1979 Quatermass serial, it differs from the earlier works in being explicitly set in the future, however soon. However, unlike the majority of the works, it’s a vision with no substantive technological shifts or “fantastic” elements: there’s not an alien in sight, especially none busy harvesting human protein. Rather, it extrapolates the technology of its time, taking an image from its present - late ‘60s fashion choices and interior design in tow - and projects it forward, along its logical progression with an eye toward scathing or cautionary critique of those present elements in which such a future lies embryonic. It should, it seems, be the Kneale work most likely to tackle “social issues,” one in which latent critiques of power - at least in bureaucratic forms - and ambivalent critiques of scientific “progress” get worked out most cogently. Indeed, the elements are here, including for the first time in his work, a straight glance at straight sexuality.

(That said, using the representation of hetero sex to discourage hetero sex and the very reproduction of the species itself is a) awesome, and b) in its own way, about as queer as one can get.)

In addition, it appears to be prescient, accurately or even uncannily predicting certain developments in mass culture, therefore confirming its assessment of its own present and trendlines. Prescient how? A sketch of the rest of the show’s narrative makes it evident. As Nat and Deanie are learning of their daughter’s potential low drive, the broadcasting apparatus has discovered that in addition to their constant production of apathy, it’s important for audiences to blow off a little steam, to tenuously release a portion of the much-avoided tension of the past via its supposedly safest outlet: laughter.

But their attempts at comedy fail miserably, especially an extended pie fight so excessive and carrying echoes of the Viennese Actionists that it is, to this viewer at least, easily the most horrifying element of the program. Instead, that laughter will come unbidden, through an accidental onscreen death. A man trying to show his supposedly “intolerable” drawings of screaming faces - as if a charcoal drawing Münch-rip off could match the abjection of that pie fight, let alone the porny bodies - falls from a ladder, and the low drive audiences finally laugh. Therein the discovery: it is the “real” suffering of others that will cause them to crack up.

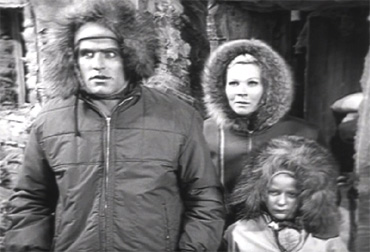

So when Nat proposes a new show - “The Live Life Show” - consisting of him, Keten, and Deanie going off the grid to live on an abandoned island in a cabin, fumblingly try to fish, chop wood, and be very familial, snuggly, and try to rediscover lost realms of affect, all recorded to be watched by the low drives, the network agrees. Because, unbeknownst to Nat, they decide to inject another character to the mix, a man who murdered his wife. Sure enough, things go to shit. Keten gets a massive infection from a small wound that the inept Nat and Deanie can’t heal and subsequently dies, and the audience roars with laughter at the parents’ grief. The murderer strangles Deanie, Nat hacks him apart with an axe, and the audience just laughs and laughs. Reality TV is born, there in the close-framed and gore-spattered face of a man actually trying to survive a set of ridiculous artificial constraints, blundering his way through the loss of long-remembered and passed-on practices of survival.

The reasons to see this as especially prescient are obvious enough, less in terms of SPORTSEX than in terms of the latter show, which indeed reads like Big Brother shot through with Survivor. But to celebrate it for this reason makes little sense, for two reasons. First, just because something happens to correlate with future cultural conditions doesn’t make it necessarily interesting, especially if it simply reiterates what we think we know about those conditions.

Second, in this case, while its shows have much in common with what was to come, it’s utterly wrong on how audiences will interact with them: not the supreme distantiation of the mocking laugh (as much as certain self-valorizing audiences veil their pleasure behind the cover of “ironic enjoyment,” one of the grand lies of the past two decades), but real investment, interest, and participation, especially with the connected fantasy of becoming a reality star oneself and the phenomena of microfame. In fact, arguably the eeriest moment of its historical projection doesn’t lie with reality TV but with the moment in which Nat, unable to invent a story to lull sick Keten to sleep, simply says, again and again, “I like you. I like you. I like you. I like you. I like…” Or, in other words, the central affective logic of Facebook, decades before its rewiring of our temporal and libidinal faculties.

Just as the prescience of The Sex Olympics isn’t the aspect of actual interest, so too its “politics,” which are exceedingly conservative, not because of whose “side” it comes down on but because it plainly cannot think class, race, gender, or any other relation and institution. It can’t think them for the obvious reason of their sheer absence: other than the test audience of low drives, we never once glimpse the world at large, where they supposedly languish and die young. We never get any sense of a rather important point: is the world still capitalist? After all, there’s no mention of needing the low drives to work, just to stay calm and stop breeding so much. As Kneale put it, “they are kept on and looked after quite kindly until they die at the age of about 28. In their few brief years of consciousness you pacify them by giving them as much pornography as they can take.” Sure, but is value-production off the table? We're in the dark , accessing the missing trajectory only through the perspective of its scattered, albeit infodumpishly direct, retelling by the high drive programmers, as well as dropped hints of automated production and the end of scarcity. And so it reduces any historical connective tissue between the present of its making in the late ‘60s and the near-future present of its plot to determinations of the dangers of a technology as such (television), permissiveness as such (pornography's fall-out), or superfluity as such (excess populations). These are then spun together into a vision of managed decadence, soft power totalitarianism, and a neo-caste system that, as with Huxley and Orwell, is both less convincing and less frightening than what actually happened and continues to, as massive economic inequality and the promise of social mobility are proven to be wholly, if not necessarily, compatible.

If it’s neither prescient nor “political,” why spend time with The Sex Olympics, other than for viewing pleasure? I'm not interested in providing a conclusive reading of it but, first, in using its occasion to offer materials by which it could be read by others and, second, well as to draw out aspects of Kneale’s work that clarify why certain efforts to read or judge them on the basis of their hidden politics or their prescience, as so much speculative fiction is treated, is a severely limited enterprise. I’ll end, instead, by returning to those peculiar materials, especially to those sticky substances that coat, gild, splatter, and get everywhere in this restricted world.

Unlike that poisonous synthetic food, the things that stick to bodies in The Sex Olympics aren’t the product itself. But they are its justification (the stickiness that visibly marks class difference and yet is doubled onto the unmissable caked make-up on the high drives themselves, who look as if their faces would come off on your hands), its supplement (the rhinestones, the glitter), and its haunted echo (that seeming ash, that toxic dusting). More specifically, though, this world is constituted around materials whose peculiar properties come untethered from, and turned against, the perpetuation of the very purposes for which they make sense. So it is that there will be much cum and wetness and froth and saliva, but with the purpose of making the audience not horny, of halting sex and reproduction entirely. There will be food, in a pure liquified, nutritional state, but it will be thrown and consumed by two fat men with the purpose of making the low drives not hungry, stopping them from calorically reproducing themselves. There will be pies in face to make laughter, but they will be answered stone-faced. There will be tears, pouring out from the grieving, but they will make you not sad but viciously joyous, just as there will be gore, and it will cause not disgust but conviviality and laughter all around.

It’s this fundamental disjunction that’s at work in this show, a splitting of materials against themselves. That disjunction will be managed by the central technique at hand, television, which here is not a material, not a recording device that freezes the ephemeral. Instead, it’s ongoing obliteration, not just of history but of memory itself, through constructing a opaque and peculiar relation between what will never touch otherwise: the two classes, and their respective spaces.

http://youtu.be/mu45tI7wunM

That non-contact is countered, though, by the phenomenon the show constructs as its true point of horror, that riotous laughter in the face of suffering. Internal to the show’s logic, it can only appear as shuddering horror, mimed for the audience in the face of a programmer who stares gibbering at the bloodied, howling face of axe-wiedling Nat as the laughter peals out. This is because it answers the tremendous gap created in the show’s world between humanity in the generic (the low drives as mere human substance) and everything that would specify and qualify it, all the historical determinations that are pointedly missing from that world. Reduced to the generic, to just carrying on, that laughter becomes an apparent betrayal of the species, the Kneale revelation seen elsewhere here uncovering not alien inheritance but television itself as the bearer of our latent auto-treason.

All well and good, except for one glaring absent detail the show especially can’t give: the low drive audience isn’t laughing at human suffering in general, they are laughing, peculiarly, at the particular suffering of a high drive. It is what might be, and has been, called class hatred, the laughter of what is historically reduced to being human and nothing more at the misfortunes of those who help ruin them. Because, at the end of the day, whether or not class relations coherently persist in this world in which only the upper class appears to work, watching a privileged man - one who spent years laboring to shorten and worsen the life spans of millions of viewers - flail ineptly with a bloody axe in a cabin for the benefit of those viewers’ entertainment is pretty damn funny.

Not to mention when seeing it in color. Because, it should be clarified, the semblance of ash on those initial bodies, the origin of this essay’s line of thought, was a consequence of a loss conditioned by television itself. The Sex Olympics was not shot in black and white: it was made, and shown, in color, garish color, blaring, psychedelic, glittering, golden. But just like the walls in The Stone Tape, these were wiped by the BBC and recorded over, because as this show is so determined to point out, television was no friend of memory. The very capacity to see the show now was the result of a discovered 16mm black and white copy of it. It took its images becoming another medium, placed onto film, to allow it to be seen. The irony is viciously apt: a program about how the elision of memory is exacerbated by television will be erased by television itself, to exist only in the fleshy hardware of human minds, until now, where it can be seen again in the era of digital storage.

But seen only as ash, not as gold. And yet, through that loss, through that failure of television and an accident of material memory, this substance smeared on extras in a BBC studio could come to be seen as other, as radioactive ash falling over them. I can’t help but think of Vittorio De Seta’s comment about television’s introduction into Italy and the consequence it had on cultural memory: ‘‘We are all afraid of the atomic bomb, but that only could go off. This has already exploded.’’