I put it to you that “politics” is not only not a useful word, it’s an actively harmful one. Everything is political, so the “political” can be nothing in particular. And this means the particular can't be anything.

Think of it this way: when we say things like “the personal is political,” for example—or attach an adjective like “sexual” or “identity” to politics—what we really mean is that the sense of the political sphere which excludes mere personal concerns (like sex, or sexual identity) is bogus and wrong. We are right to say this, excluding the personal from the political is bogus and wrong. Dignity is as much a part of the struggle for labor rights as are things like salaries and benefits, and the dignity of marriage no less so; any one who thinks a civil union is the same thing as a legal marriage is missing the reason why reactionaries are defending that very difference, tooth and nail, and why legally distinguishing between people who have real marriages and people who have fake, pretend marriages is really about legally distinguishing between people. And, more generally, the subject of politics is subjectivities, not just Objective Facts: the kind of clothes you wear, the kind of things you post on facebook, the expression on your face as you do your job, even how you talk to your family, all of these things are “political,” and if you don’t think so, experiment by adopting with politically unorthodox choices in your public behavior.

The problem, then, is that nothing left of the word once we have declared politics to be also personal; if politics is anything, it’s everything minus the personal, so adding the personal back in—as we must—forces the essential meaninglessness of the word “political” to the surface. If it can’t distinguish between the act of casting a presidential ballot while thinking about the Supreme Court and the choice of how, when, and whether to have sex with whom—or if it makes these seem like qualitatively different and wholly unconnected things—then the word “political” is not helping us think about the world we live in. It’s only describing the difference between voting and everything that isn’t voting, which is pretty much everything. That voting and everything else are connected, however, is entirely the point of voting. But the fact that it’s even necessary to say that “everything” is political demonstrates how the word “political” falsely asserts that some things aren’t political, and how this is its only meaning. And if everything is political, then the word tells us nothing interesting: how you vote and how you have sex are both political, which demonstrates how unhelpful the word itself is in describing how they are differently so.

* * *

Of course, the word must mean something, right? We use it constantly. So what do we mean?

Here is where we go from “the word is meaningless” to “the word is pernicious.” If the word “politics” is incoherent, it’s also a useful kind of incoherence for people who want to exclude certain kinds of perspectives from the dignity of being part of real political discourse, to exclude certain subjects and subjectivities from being publicly recognized as objectively important.

If something is merely personal, after all, the state has no business with it, nor do the rest of us. It’s outside of what “we” thing about as a “we”; that’s just what “you” think and do, or “I,” or him or her, so it doesn’t scan as the concern of the total body politic. But every time we use that “we,” we silently imply the exclusion of those excluded persons, as surely as when we say things like “so and so looks an American.” But I would extend that argument to say that every time we take the word “politics” seriously, as if it actually means something, as if some things are categorically outside our concern as a first person plurality, we not only legitimize a particular political hierarchy of interest—say, “property” is political, but “marriage” is not—but we hide the fact that we are doing so, as if that distinction is inherent in the things themselves. But it never is. There is no objective politics; there are only choices between different people’s different interests. We always decide what things “we” will declare to be politically interesting, politically important, politically grave. But since we want to make politics and personal a difference between objectivity and subjectivity, we often work very hard to forget what we always, also, know: politics is personal.

* * *

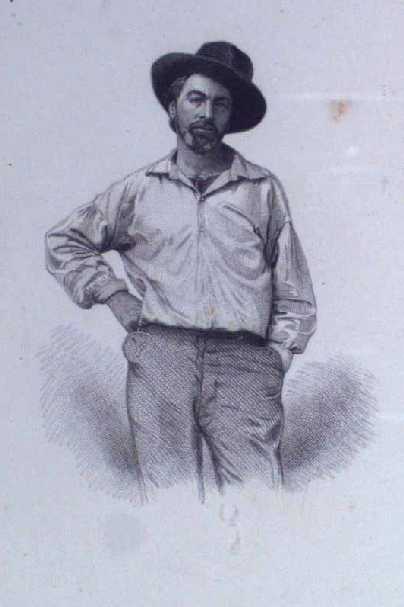

We learned to stop thinking politics was personal at the moment we started pretending that everybody was an adult white male, that “adult white male” was the definition of objectivity. In American, this was the historical moment when it was vitally important to expand the franchise to the masses, as a whole, while simultaneously defining down the kind of person who counted as part of that mass, when American went from looking like this:

To looking like this:

You can call this era the Jacksonian era, if you like, as it captures something important about the process of expanding the voting franchise to all adult white males—by eliminating the property requirements that had kept voting in the hands of the wealthy elite—and reshaping the body politic from cultivated Anglophiles to frontier roughnecks. But if this conceptual and legal transformation made a different kind of political subject possible—since “citizen” no longer meant “not-poor”—it shouldn’t take you long to notice what didn’t change between those two images. This was not a qualitative shift from aristocratic tyranny to democratic politics, it was just a reshaped sense of who got to define what was publicly relevant to the body politic. Before, it was adult white men with property; after, it was adult white men. Different bodies, sort of, but defined by the same basic principle: the people who defined American politics, its concerns and it validity, were the people who had particular kinds of bodies. Your person defined your politics. Your identity was your politics.

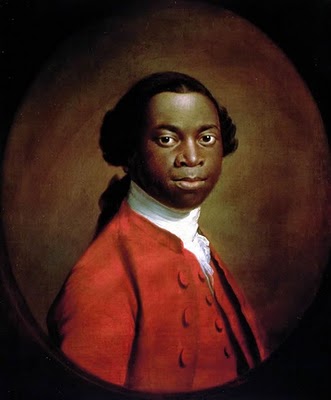

There is no more pure expression of identity politics than this, after all, and it names the paradox of American democracy: the most expansive claims to democratic universality were being made at (or are now retroactively attributed back on to) precisely the moment when many of the 19th century’s most repressive exclusions were being formed. Women and African-Americans lost the right to vote at the same time at the same time that all white males were gaining it; before “universal manhood suffrage” was established, this person could vote in many parts of the United States, if he was free and had property:

In many specific cases—and generally, as a broad historical trend—the creation of new restrictions and the relaxing of old ones happened at exactly the same time. In 1821, to pick a single famous example, New York wrote a new state constitution and they removed property restrictions for white men. But by specifically allowing those restrictions to remain in the case of black men, property was transformed from what made all adult men equal into the thing that could allowed inferior men (black people) to overcome their racial deficiency. It literally replaced class with race as the limit point for democratic participation. “We” became democratic in the process of disenfranchising alternate forms of “we.”

* * *

At the moment in which all of this was happening, voting was hugely important. No one understood this better than politicized African-Americans and women, people for whom the ballot was the first step to everything else. It was in this context that the joke “If voting changed anything, they would make it illegal” is most meaningful: they did, because it did.

But voting was also the manifestation of a more symbolic form of identity politics, and preventing some categories of people from voting was also about identifying which categories of people counted as the public. The people who could vote were also the people who were real Americans. Which is another way of saying: defining who the “people” was gave the government a mandate to govern of, by, and for adult white men. This was the most fundamental principle of the American revolution, after all: it was not enough to be represented in parliament, passively. One had to have the ability to select one’s representatives for one’s consent to be implied. This was the inescapable meaning of phrases like “no taxation without representation,” after all, since while Britons demanded that Americans were represented in British parliament, the Americans claimed that they had not consented to be represented by the people who were taxing them, because they had not voted for them. The American revolution settled the matter, in theory—making British-Americans into Americans—and though it would take decades for practice to catch up with the principle, the rise of mass politics in the United States was the period in which “universal manhood suffrage” became the standard for what democratic politics was supposed to be: the extent to which all citizens not only were represented, passively, but actively represented themselves.

The flip side, however, is that as the US moved towards a sense of the political in which all adult white males could vote, because all citizens should vote, this meant that only adult white males were citizens, because only adult white males were political, which meant that politics was the domain of adult white males. And so, the domain of the political came to be the domain of a “we” which was adult, white, and male. “Democratic” inclusion came with racialized and gendered exclusion.

I don’t think happened because these people were bad people, though of course, many of them surely were. It happened because defining who the citizen is cannot help but define by exclusion who the citizen isn’t. And the same is true about “politics,” which not only always refers back to who the body politic is, but by marking as off-limits the things which are not political, defines what kind of person’s experience can be respected by the public sphere, what kinds of bodies are of public interest and why.

So I put it to you that “politics” is not only not a useful word, but it’s an actively harmful one. Since everything is political, the “political” can be nothing in particular. It can be no person, only a white mythology. But when we mistake that white political for reality, we exclude the personal and the particular, the only things there are. And when we make “politics” into a one-day ritual choice between austerity and austerity, drones and drones, and wall street and wall street, it becomes very easy to mistake the difference between socially moderate and frighteningly reactionary for the entirety of politics, to mistake what little we have for everything there is. Because, after all, if this is not politics—and it’s all that there is—then there is no politics. And there must be, since politics is everything, plus the personal.