[New translation - although anonymously signed, this comes from the Ludd circle in Genova, a group of anti-state communists whose texts slipped between SI-inflected bits of rhetorical prankery, serious reflections on anti-work and illegality, and texts like the one that follows, a clear and fierce indictment of the idea that those rioting couldn't really mean to be that destructive, now could they?

(For further proof of the occasional genius of the Ludd crew, consider this:

i.e. CALL TO THE INFANTILE PROLETARIAT AGAINST BOURGEOIS INFANTILISM)

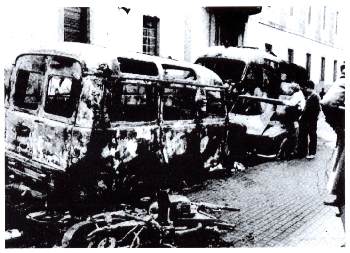

The occasion for this specific text, from April 11, 1969, was a mass uprising in Battipaglia, a southern Italian town in Campania, occuring just two days prior. In the period leading up to this, the town faced the planned closures of two manufacturing plants, one for tobacco, one for sugar. This would have crippled the town, given that the two were the largest employers in a region already facing population exodus and perennial poverty. Protests began and during a march on April 9th, cops did what cops do perennially - i.e. kill the citizens they allegedly protect, here in a particularly stark fashion, murdering a 19 year old worker and a middle school teacher. What followed the next day is unsurprising: the town took serious revenge, against the cops, the planned devastation of their community,

and many objects (such as 200 cars that got torched) alike ...

while nationwide calls emerged for the immediate disarming of police. It's in this context that the Ludd text was written, on the night when Battipaglia was still, and with no exaggeration, burning.

"An exemplary revolt"

When people revolt, they know their objectives: at Battipaglia, they didn't bring petitions to the prefect, but they tried to set fire to the town hall and devastated the tax collector's; they didn't chit-chat with the forces of order, but they did besiege them in the cemetery and burned the commissariat;

When people revolt, they know what they want: to have done with all oppression and its hateful symbols, to have down with exploitation and its managers.

The bourgeosie worry and paint the situation in bleak hues: aggravation, hooliganism, confusion, anarchism: NO, IT'S MUCH MORE SIMPLE - PEOPLE WANT TO HAVE DONE WITH THIS SOCIETY. They've taken the path that has gives no access to those who follow the logic of the good bourgeois or the orderly citizen; revolutionary actions can be recuperated only by lies or silence.

No one is helped by the appeals to the government for calm, the cynical telegrams of Saragat

The Italian president from '64 to '71, a reformist socialist who left the PSI because of their links to the PCI.

The Italian president from '64 to '71, a reformist socialist who left the PSI because of their links to the PCI. And what does the opposition do? The opposition that's serious, that's communist? It tries to include a victory within a tradition of defeat, tries to circumscribe the fire, joining in the effort to form a solid cordon sanitaire around Battipaglia.

But the real objectives, those of the revolt, where did they end up? These were trampled, shoved back inside. Who speaks of the victories, the real, exemplary actions? Not l'Unità who weeps over the dead, seeing it only a victory for the opponents, and tries to give to workers nothing more than an image of their impotence, of the frustration of defeat. And the only way that remains is to re-enter the movement in the only way they know how, that of bourgeois democracy.

We delude ourselves daily - though civil society helps us in this illusion - that the things that surround us could be ours, that their use, their ownership would be permitted, however mediated through money, a salary, or whatever else it may be: that's the illusion that Battipaglia destroyed today.

When the exploited negate and burn a society that oppresses them and affirm their real power over things, when they seize a city, the forces that today hold the power destroy those people, they murder them because bourgeois society, expropriator of man, can't tolerate being expropriated.

For those exploited who look toward the fire of Battipaglia with hope, there are no intermediate objectives in front of them, no demands to put to democracy. Because we don't defend - we attack - there's no need to ask for the disarming of the enemy, just weapons for comrades. And if for us the moment hasn't yet come, there's no need to spill crocodile tears for our comrades from Battipaglia, but to learn that if we don't attack our enemy, our defeat will be permanent.

A group of comrades

Genova 4/11/69