Asylum inmates of yesteryear were none too crazy about the food served them

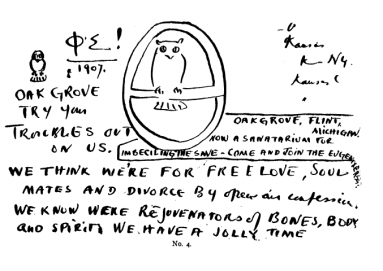

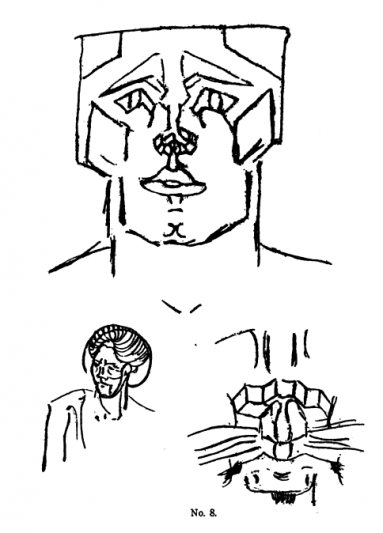

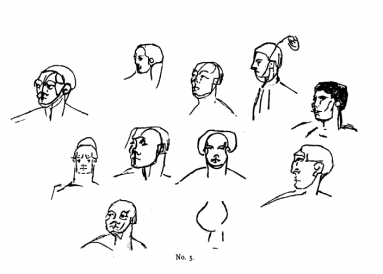

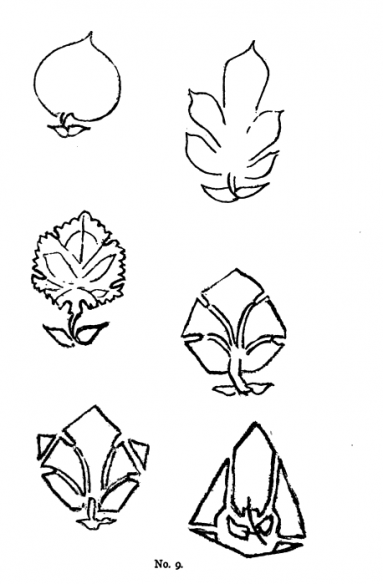

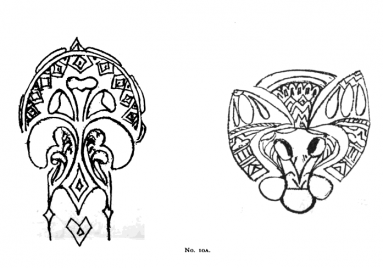

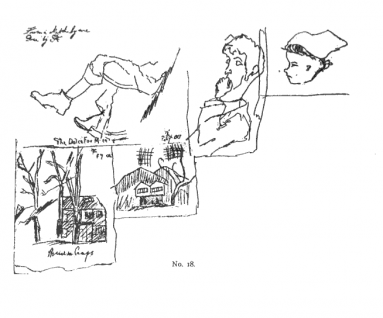

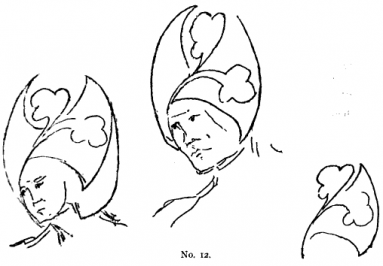

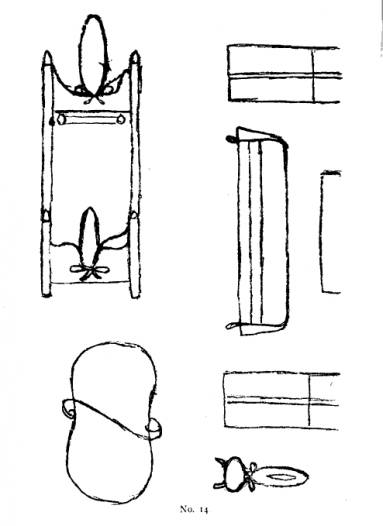

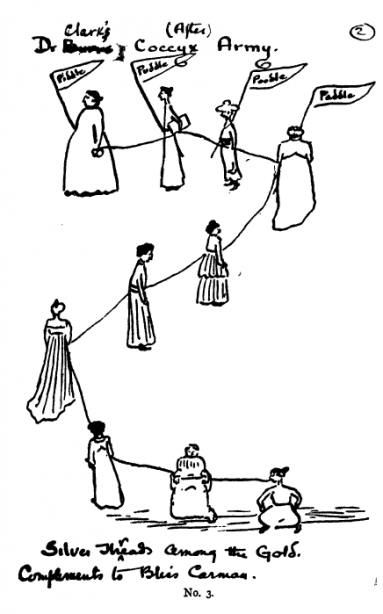

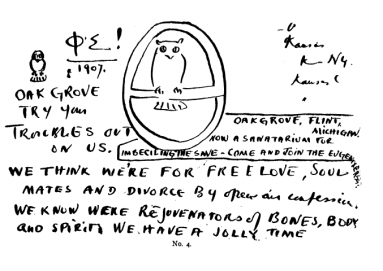

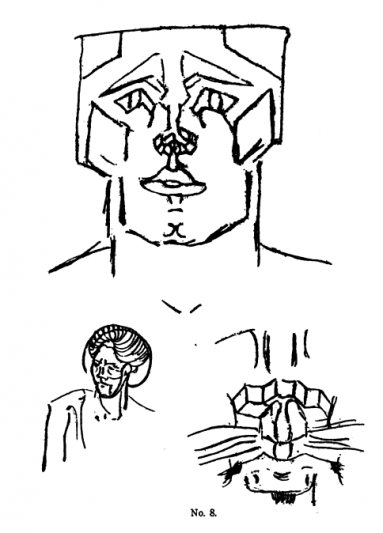

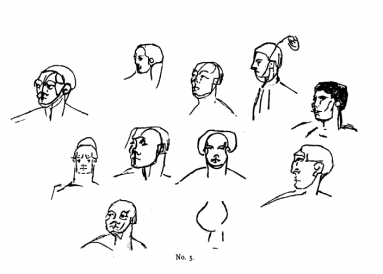

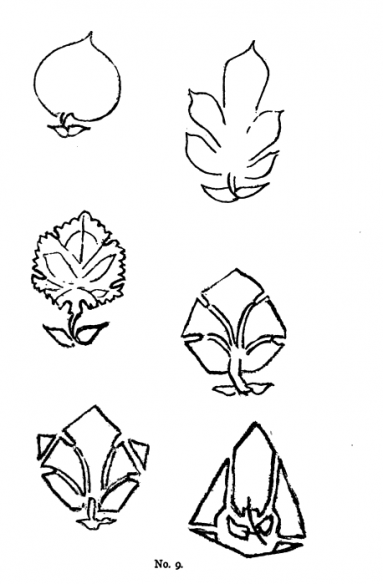

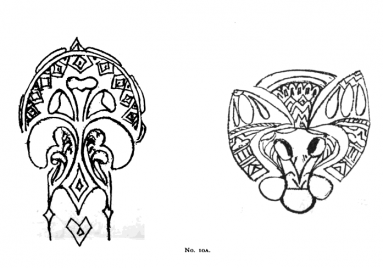

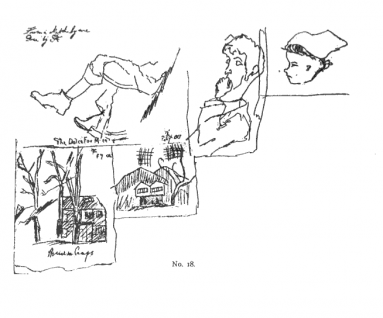

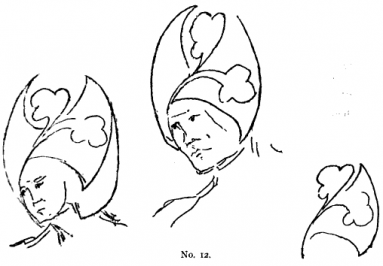

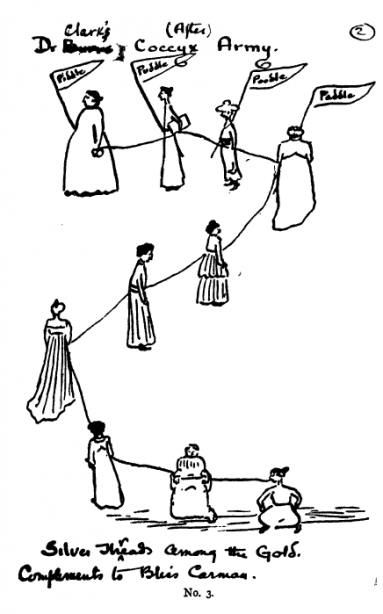

Images from the psychiatric patients of Dr. C.B. Burr, as featured in his 1911 article on the subject, "Art in the Insane."

"The period I have been trying to describe ... was, I can truly say, the most gruesome time of my life. And yet it was also the holy time of my life, when my soul was immensely inspired by supernatural things, which came over me in ever increasing number amidst the rough treatment which I suffered from outside; when I was filled with the most sublime ideas about God and the Order of the World." --Daniel Paul Schreber, Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1955)

What did the insane eat? In Bram Stoker's

Dracula we find the lunatic Renfield dining on flies and spiders. Ken Kesey describes attendants bringing "identical trays of muddy-looking food" to asylum patients in his

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. And in her memoir of her time in a psychiatric ward,

Girl, Interrupted, Susanna Kaysen recalls "cutting old tough beef with a plastic knife, then scooping it onto a plastic fork."

"I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; / I lift my lids and all is born again. / (I think I made you up inside my head.) --Sylvia Plath, "Mad Girl's Love Song" (1951)

The cuisine of the average mental hospital could drive most people insane, if they weren't already. The residents of Bethlem Royal Hospital in London -- Europe's first hospital to specialize in treating mental illness and the source of the word "bedlam" -- ate mostly bread and drank mostly weak beer. They didn't even get breakfast. When the hospital opened its doors to the insane in 1403, conventional medical thinking deemed it ill-advised to feed lunatics anything to break their nightly fast. They were allowed only supper (called lunch today) and dinner. And these meals had to be bland and meager so as not to upset their delicate systems.

"This is a field where fads and fancies flourish. Hardly a year passes without some new claim, for example, that the cause or cure of schizophrenia has been found. The early promises of each of these discoveries are uniformly unfulfilled. Successive waves of patients habitually appear to become more resistant to the newest 'miracle' cure than was the group on which the first experiments were made." --Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Mental Health, 1961

"There is no great genius without a mixture of madness." --Aristotle

Natural philosophy was to blame for these unfortunate dietary restrictions. Leading minds of medieval Europe believed four bodily humors determined health and happiness: black bile, or melancholy; yellow bile, or choler; phlegm; and blood. Each corresponded to one of the basic elements -- earth, fire, water, and air, respectively -- and, among other things, influenced individual personalities. Moody, serious people were believed to be dominated by black bile; restless, touchy people by yellow. Pluck and high spirits characterized the person dominated by blood; patience and calm, the person governed by phlegm.

Unbalanced humors led to insanity. According to the ancient Greek physician Galen, from whom much of the information on humors came, all mental disorders resulted from brain damage brought on by humoral changes in the body. Too much dryness made one irritable, and too much moisture led to sluggishness. Sanity was maintained by keeping a happy medium between the two.

"Science has not yet taught us if madness is or is not the sublimity of the intelligence." --Edgar Allan Poe

If one did become unbalanced, a change in diet was advised. Depressives were warned against eating the flesh of oxen, goats, asses, camels, wolves, dogs, hares, and snails -- a list that shows just how adventurous the Greeks were at table. Red wine could also cause trouble. And all people, whether sane or insane, were to avoid consuming too much food in general, because "the mind that is choked up with fat and blood cannot perceive anything heavenly."

"For madness threatens modern man only with that return to the bleak world of beasts and things, to their fettered freedom. It is not on this horizon of nature that the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries recognized madness, but against a background of Unreason; madness did not disclose a mechanism, but revealed a liberty raging in the monstrous forms of animality." --Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization (1964)

It was on June 1, 1889 that Brown-Sequard before the Société de Biologie in Paris read his address on the hypodermic injection of testicle juice -- "sue testiculaire," "liquide orchitique." He performed the experiment partly in animals, partly in himself. His used the following method: He ligatured and at once removed the testicles of young dogs and guinea pigs, cut them into pieces, and rubbed them in a mortar with a small quantity of water. This mass he filtered through an ordinary paper filter, and the liquid was ready for use. It was said to give lunatics a great sense of well-being.

And so bread and beer it was, with maybe a bit of beef or cheese thrown in for variety. (Fruit was entirely absent.) An austere diet, to be sure. But patients were lucky to get it: Their attendants thought them little more than animals, and anything that might ease their discomfort was given begrudgingly. In his 1684 book

The Practice of Physick: Two Discourses Concerning the Soul of Brutes, Thomas Willis, one of the first English physicians to write extensively on the proper treatment of madness, said that the insane, having lost their reason, were feral creatures who enjoyed superhuman strength. "They can break cords and chains, break down doors or walls … they are almost never tired ... they bear cold, heat, watching, fasting, strokes, and wounds, without any sensible hurt," he remarked. If madmen were to be cured, he concluded, they had to regard their doctors as their "tormentors" to be held in awe accordingly. This amounted to a license to abuse, for only from "discipline, threats, fetters, and blows" will the mad become "meek and orderly." This is also why they recover more quickly if they are "treated with tortures and torments in a hovel instead of with medicaments."

Keeping the insane on starvation rations was another way of breaking their spirit. Not until the 18th century did they receive anything more substantial. In 1730 "Turnipps & Carrotts" were added to the daily bill of fare, as was a "better sort of small beer." Holiday menus became more cheerful, with mince pies, strong beer and plum puddings at Christmas, veal and hot cross buns at Easter and Whitsun, and even pancakes and fritters on Shrove Tuesday. By the 1720s there appeared "Furmity" -- that is, frumenty, a sweetened wheat porridge -- and in 1761 veal became a mainstay on the menu "during the Season," which ran from "from Lady-Day to Michaelmas." Butter became a common sight, and by the early 19th century, potatoes rounded out patients' diets. Their portions also grew.

"You have to go on and be crazy. Craziness is like heaven." --Jimi Hendrix

Even more important, perhaps, was the return of breakfast. Though it often consisted of nothing more than "a large bason of water-gruel" and some bread, it was a welcome change. And things only got better from there. By the 1780s patients also received eight ounces of meat on certain days. They got a "pint of small beer" and a generous portion of bread at every dinner and supper. Potatoes could be had by the pound. Patients who were also physically ill could receive special orders of "Wine," "Rum," "Oyle," "Sage," "Fowl," "Oat cakes," and "Fish." This was remarkable, for during this time Bethlem was almost entirely a place for the destitute. Wealthy lunatics -- who, more often than not, were simply annoying relations and querulous wives -- entered the care of private asylums.

Treatment in Britain during this time varied. In Nottingham for instance, patients received every day for breakfast milk porridge, coffee, and bread. Dinner was usually Australian meat, bread, vegetables, and beer. Some days they got a fruit pudding or an Irish stew. And once a week they received salad. Those who worked in the garden, laundry, or in some other capacity received extra bread, cheese, and seed cake.

"Of the private asylums in Ireland, the patients generally subsisted on potatoes and milk. In Armagh, for example, breakfast was one quart stirabout with milk, dinner 3 lbs potatoes and 1 quart soup or milk, and supper was the same. In Londonderry, they got much the same, save that the milk was more often buttermilk, and sometimes they got oatmeal." --From The Sessinal Papers Printed of the House of Lords, or Presented by Royal Command in the Session of 1846

Despite these small improvements, conditions in both public and private asylums were largely unpleasant. Time did nothing to change this. By the 19th century, institutional stinginess became something of a science. Meals were sent up on wooden trenchers in precise portions, everything weighed with exactitude: seven ounces of bread and butter for breakfast, four ounces of mutton or beef with 12 ounces of vegetables and a pint of beer for dinner, and again seven ounces of bread and butter for supper. Those who worked more, got more. Those who didn't work had to be content with what they received. And those who neither worked nor meekly accepted their due servings had their meal administered "by means of a stomach pump."

In the United States treatment of the mentally ill had followed a decidedly different path. "The diet afforded in this asylum," noted Pennsylvania Hospital librarian William Gunn Malin in 1830, "is more generous than that of many similar institutions, judging from the bills of fare, and other statements occasionally published." This was true. For one, the patients got breakfasts of bread and butter, hashed meat, fish, potatoes, and "Chocolate or Coffee at pleasure." Dinner was served in an elegant dining room and featured two kinds of meat -- usually some combination of beef, veal, mutton, or pork boiled and roasted, with a variety of vegetables. For dessert there were puddings, pies, and fruit (apples, melons, and peaches were all favorites). Bread was given freely, as were milk, sugar, and molasses.

"They called me mad, and I called them mad, and damn them, they outvoted me." --Nathaniel Lee

Of course, how well patients were treated depended on how honest their attendants were. "If we had any thing that I could relish, I could never get enough of it to do me any good," recalled Phebe B. Davis in her 1855 memoir Two Years and Three Months in the New York State Lunatic Asylum at Utica. "We had of such eatables, whenever they were sent up, just what the attendants did not want. Each attendant had a rule book while they were in the house that was written by the managers, and one of the articles in that book strictly prohibited any of the attendants having different or better food than the patients. In the good halls there is not so much of an opportunity for speculation, for the attendants and patients take their meals at the same time and at the same table."

Americans didn't believe in culinary bean counting. And they didn't believe in giving the insane inferior food. The asylum bread was made of fine wheat flour, just like what the physicians got. And sometimes patients sipped delicious liquors, wines, and porter. This was true for rich and poor alike. Malin observed that no difference was "made in the diet or treatment of patients merely on account of their wealth ... no difference exists between the treatment of those who pay for their board, and those who are supported on the charity of the institution." The attendants were never informed as to which class the patients belonged. Everyone ate together, and everyone ate well.

Yet this period of enlightened treatment was brief. By the end of the nineteenth century, most American institutions were overcrowded, miserable places.

What happened after dinner? The physicians of Pennsylvania Hospital saw to it that patients had many diversions. They could go bowling in the spacious alley, play games in the day room, or admire the greenery of the greenhouse. There was a farm too, which many of them worked. It furnished the asylum with fruit, vegetables, and fresh dairy. Given the circumstances, life there was as idyllic as it could be.

Recipe for a cure for nervous prostration from The Family Doctor: A Cyclopaedia of Domestic Medicine and Hygiene (1890): "Take one hundred grains of each -- Valerianate of quinine, Valerianate of iron, Valerianate of zinc. Mix, and divide into one hundred pills. Take one or two pills, three times a day."

It's strange now to think there was ever a time when we treated the mentally ill with kindness. But menus don't lie. How we feed people betrays how much we value them. Early Americans fed the insane well because they considered them citizens of the republic, who as such merited friendship and fellow feeling. Through such kindnesses, it was believed, the mad would recover their wits and once again join productive society. It was a far more progressive approach than anything practiced today, where psychiatric hospitals are defunded and converted into upmarket condos and what little we do give, we give grudgingly.