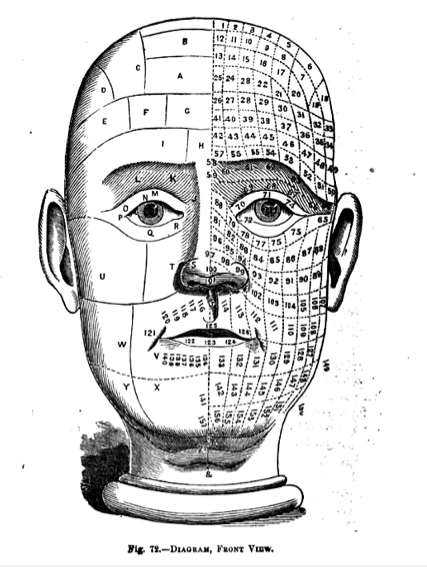

Its rebirth isn’t called physiognomy, of course; it’s called something like "a universal conception of personality structure," which sounds much less nefarious than a discredited science based on phrases like “I have never yet seen a nose with a broad back, whether arched or rectilinear, that did not appertain to an extraordinary man.” Researchers use facial characteristics to explain things like gaydar, the trustworthiness of baby-faced adults, and women’s supposed preference for manly-men, and even conscientiousness. Even more so than with modeling, modern adaptations of physiognomy are often specifically not about beauty; they’re about classifying features in order to (supposedly) understand more about how we function. Physiognomy has its direct progeny in these areas of study. But the more I think about it, physiognomy is also a grandparent to the extraordinary attention paid to beauty by science researchers.

I’ve questioned the scientific drive behind beauty research before, and I don’t want to be redundant. In a nutshell: There’s an enormous body of research trying to pin down what exactly makes someone beautiful (rather, what makes someone conventionally attractive, I’d argue), and how/why people react to good-looking folks the way we do. I suspect it’s the very mystery of beauty that drives academic research behind beauty. There’s so much literature about how beauty leaves us powerless in its wake; why wouldn’t we want to demystify it in order to lessen its supposed power over us? (The next logical question question is gendered—why do we want so specifically to put a fine point on women’s beauty—but that’s a different post.)

Beauty science is the richest heir to physiognomy. What physiognomy attempted to do was pin down the mysteries of character and behavior, using a highly coded and essentially arbitrary system of classification. What scientists and economists are attempting to do with its glut of studies on beauty is pin down the mystery of fascination, using the highly specialized—and often subjective—tools at their disposal. When attempting to decipher what puzzles us, it’s assuring to turn to something unassailable to provide us with order. We can now look at physiognomy and see it’s ridiculous, but plenty today are happy to give credence to evolutionary psychology as it pertains to beauty without giving it a second thought. We can see the blatant racism, or at least the potential for it, in evolutionary psychology; we may not be as able to see how it enshrines subtler beauty norms, in part because there’s so much mystery, doubt, fear, and wonder about human beauty, particularly our own. (Is it possible to read any study on what determines beauty without attempting, however briefly, to figure out where you’d fall by its measure? I once actually measured the circumference of my wrist because it was supposed to tell me something about my desirability.)

I’m not trying to say that beauty researchers are as full of hocus-pocus as physiognomists. Where the father of 18th-century physiognomy Johann Kaspar Lavater said, “Meeting eyebrows, held so beautiful by the Arabs...I can neither believe to be beautiful nor characteristic of such a quality,” the new set of beauty science at least attempts to set objective criteria. (At least, some of the time it does; other times it’s just as subjective as a 1794 fortune-teller. The aggregate study from Daniel Hamermesh that got a lot of ink last year examined five studies on beauty; four of them relied upon the beauty assessment of exactly one person.) I’m also not saying there’s nothing to the evolutionary science of beauty. I’m not qualified to make that statement, and it makes sense that the science of beauty, including evolutionary psychology, has a valid place in any thorough discussion of beauty. But what I’ve repeatedly found is that when people rush to bring in scientific “proof” of why we find certain features beautiful, it shuts down the conversation instead of enlivens it. It’s a way of saying, Sorry, babe, there’s nothing you can do about it, whether “it” is the incessant ogling of a woman with the desired waist-hip ratio, or someone feeling excluded from the realm of the beautiful because her features don’t match up quite right.

And that’s just a shame. I don’t think that the people behind these studies mean to shut down discourse about beauty; I think the actual researchers want to do the opposite. The most prominent researcher on the science of beauty, Nancy Etcoff, presents her work as a launching point, making it clear that she just wants the science of beauty to have a place in the conversation; her book, Survival of the Prettiest, is as much a cultural study as it is a scientific one. Actually, Etcoff’s introduction to her book makes it clear that she’s only trying to bring science back to beauty. Science had been concerned with looks at one point, she writes, until such studies became discredited as arbitrary, racist, and generally faulty. The science she was writing of, of course, was physiognomy.

Last week I wrote that it’s useful to look at a now-discredited pseudoscience in order to understand the collective cultural forces that go into taste-making, specifically in the modeling industry. But the consideration of physiognomy has a far more direct application to most of us: If we can give the science of beauty the same skepticism we now give to physiognomy, we may be able to see how little of the story evolutionary psychology really gives us when it comes to looks and attraction. Again, I’m not saying that Etcoff and the like are the equivalent of Lavater, making wild proclamations based solely on their own experience. But physiognomy’s, erm, limitations can illuminate those of the beauty sciences. More important, they can show us that there’s something more at stake than simple research. Lavater wrote Physiognomy in 1775—the early years of the Industrial Revolution, which would change the entire world more rapidly, and more radically, than any developments that came before it. The science of beauty began to see a resurgence in the 1960s, another time of blistering change. So let me ask you: What is going on now that might make scientists and economists put hard numbers on beauty? What sort of threat might a pretty face—or, for that matter, a not-pretty one—pose to social order? Why might we want to boil down beauty to a series of tables and charts, measurements and ratios, and why now? If we understand beauty in a rational way, who benefits—and whose power is curtailed?