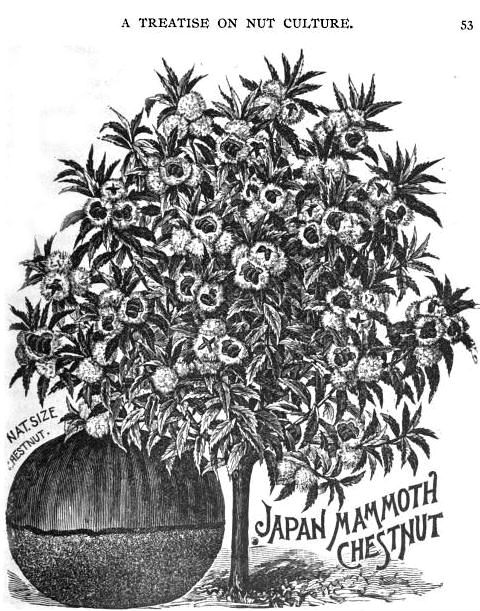

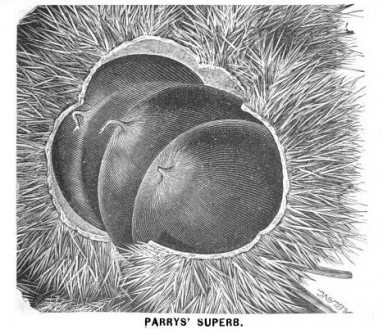

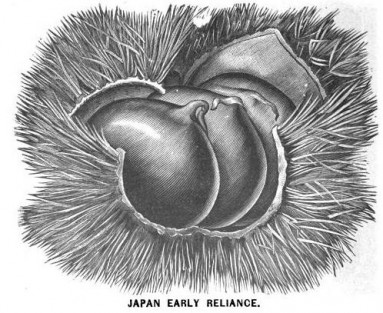

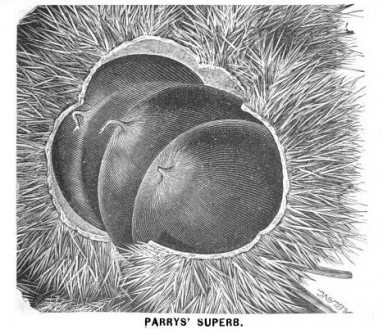

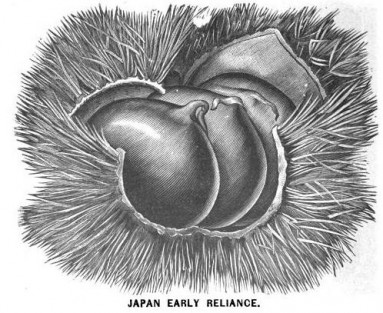

Illustrations from Nuts for Profit (1897)

Chestnut season has passed. No more do the dusky, burnished hulls brim from bins in supermarkets and gourmet shops. No longer does their sweet, musky scent tempt passing shoppers to buy them -- a good thing, perhaps, when today they command a price too high for the budget-minded; but a strange development when you consider that for centuries chestnuts fed hapless farmers, friendless students, luckless gamblers and helpless children.

Alexander the Great had chestnut trees planted along his armies' path so that his troops might always have something to eat. The Romans followed suit. With milk and cheese they ate their chestnuts. Thus fortified, they conquered Europe.

No one of any real means thought much of the small, shiny nut which appeared so plentifully in the forests of France and Italy. The Roman historian Pliny found them unremarkable, self-important even. They made "much ado about nothing," he felt, their "armour of defence, in a shell bristling with prickles like the hedgehog," suggesting an altogether outsize sense of desirability. The fact that "nature should have taken such pains thus to conceal an object of so little value" much bemused the noble Roman, but few of lower station shared his opinion. In the eyes of the poor chestnuts enjoyed a worth almost surpassing that of gold, for the simple reason that without this produce so distasteful to Pliny life would prove impossible to sustain. At breakfast, lunch and dinner, day in and day out for most of the year, an unchanging bill of fare centering on chestnuts was all humbler sorts looked forward to.

Though free for the taking, chestnuts exacted a price for doing so. Nasty, back-breaking business, the harvest lasted as long as three weeks (chestnuts do not fall all at once). After gathering them, harvesters had to free them from their burrs, a task that roughened hands and tempers. Those who husked without complaint won recognition as "chestnutters," this name reflecting their fellows' esteem. Yet even harvesters so distinguished did not escape the task that followed: boiling the freed nuts to loosen their bitter and astringent skin. Peeling chestnuts harvesters usually did before a fire, which warmed them as they worked long into the winter evenings. To peel five pounds of raw chestnuts took nearly an hour, which meant that a family of five could look forward to three hours of such work -- and this simply to prepare enough to feed themselves. The drudgery of the chestnut harvest nonetheless failed to deter people from gathering what they considered manna from heaven. Free had a flavor all its own, they reasoned, a flavor sweet enough to dispel the bitterness of toil.

Though free for the taking, chestnuts exacted a price for doing so. Nasty, back-breaking business, the harvest lasted as long as three weeks (chestnuts do not fall all at once). After gathering them, harvesters had to free them from their burrs, a task that roughened hands and tempers. Those who husked without complaint won recognition as "chestnutters," this name reflecting their fellows' esteem. Yet even harvesters so distinguished did not escape the task that followed: boiling the freed nuts to loosen their bitter and astringent skin. Peeling chestnuts harvesters usually did before a fire, which warmed them as they worked long into the winter evenings. To peel five pounds of raw chestnuts took nearly an hour, which meant that a family of five could look forward to three hours of such work -- and this simply to prepare enough to feed themselves. The drudgery of the chestnut harvest nonetheless failed to deter people from gathering what they considered manna from heaven. Free had a flavor all its own, they reasoned, a flavor sweet enough to dispel the bitterness of toil.

The rich favored a large sweet chestnut known as a marron. The more common châtaigne they considered food for pigs and peasants.

"As she was the only member of our family who could be described as a trifle 'common,' she would always take care to remark to strangers, when Swann was mentioned, that he could easily, if he had wished to, have lived in the Boulevard Haussmann or the Avenue de l'Opéra, and that he was the son of old M. Swann who must have left four or five million francs, but that it was a fad of his. A fad which, moreover, she thought was bound to amuse other people so much that in Paris, when M. Swann called on New Year's Day bringing her a little packet of marrons glacés, she never failed, if there were strangers in the room, to say to him: 'Well M. Swann, and do you still live next door to the Bonded Vaults, so as to be sure of not missing your train when you go to Lyons?' and she would peep out of the corner of her eye, over her glasses, at the other visitors." -- Marcel Proust, Swann's Way (1913)

From that toil lept a wide variety of tasty dishes consumed in a wide variety of ways. An 1831 issue of the

Arcana of Science and Art reports that Florentines gobbled chestnuts raw, cooked, roasted, boiled and dried. They mushed them, mashed them, and pounded them into puddings, patties and dense, dry cakes. Sometimes they slurped them down as soup, sometimes as porridge. When their pocketbooks permitted they mixed them with vegetables, lard and meat. This and other motley messes they munched by the bucketful. The culinary possibility of the chestnut appeared infinite. As one eighteenth-century nabob observed, "All the goods nature and art lavish on the table of the rich do not offer him anything which leaves him as content as our villagers, when they find their helping of chestnuts after attending their rustic occupations."

"A sailor's wife had chestnuts in her lap, / And mounch'd, and mounch'd, and mounch'd: 'Give me,' quoth I -- / 'Aroynt thee, witch!' the rump-fed ronyon cries." -- Macbeth, Act 1, Sc. 3 l. 4 (1606)

Yet even the most original dispositions of nut-flesh could only do so much. On occasion there would body forth considerable resentment. Large-scale exports of grain from Naples to Spain caused domestic famine in 1585. Peasants had to fill their bellies with

pane di castagne e legumi -- a dry, tough loaf made of chestnuts and legumes -- while town merchants hoarded grain to send overseas. This arrangement did not last long. One such merchant, a certain Giovanni Vicenzo Storaci, found himself one evening faced with a crowd of angry, half-starved Neopolitans. "Give us grain!" they cried. Storaci, who had more speculative than charitable designs for his stores, invited the crowd to "eat stones." Stones the mob had on their mind, but not for dining. They seized the insolent merchant, bludgeoned him to death and dragged his corpse around the square before chopping it up and feeding the bits to birds.

The Cambro-Norman soldier Robert Fitz-Stephens complained that the English peasant gives his chestnuts to "our swine in England which is amongst the delicacies of princes in other countries, and, being of the larger nut, is a lusty and masculine food for rusticks at all times, and of better nourishment for husbandmen than cole and rusty bacon, yea, or beans to boot."

Storaci's violent end stood as something of an anomaly, however; more often than not, men of business maintained the upper hand, ever scheming up new ways to profit from the chestnut's abundance. In the forests of Southern France chestnut trees grew so plentifully that merchants there saw to it that the region's peasants ate little else. It was best that peasants subsist on chestnuts, they concluded, and drink only water; for both were free for the taking and allowed peasants "to work very cheap, and do for next to nothing." Eager to increase their own margins, the British likewise investigated the profit potential of sylvan subsistence. Visiting Limousin, France during the first two years of that country's revolution, agronomist Arthur Young calculated that 70 trees covering an acre of land could feed one man for 430 days, and that an entire family could subsist on 2,800 kilograms of chestnuts and leave enough for a pig. Where peasants saw God's bounty capitalists saw opportunity to reduce labor costs: Within a budding grove grew a clever excuse for a wage squeeze.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century Lyon suffered a collapse of its textile market. Thousands of workers found themselves unemployed. In the midst of the crisis, a clever bridge and roadworks engineer, Clement Faugier, developed an ingenious way to revitalize the regional economy. In Privas, Ardéche he and a local confectioner set up a marrons glacés factory in 1882. The first of its kind, the venture was a success; it allowed an expensive and rare sweet to be produced industrially, and therefore come down in price. Not only did the factory employ the unemployed, it allowed them, for the first time perhaps, to indulge in a sugared chestnut or two.

"Under the spreading chestnut tree. I sold you and you sold me: There lie they, and here lie we. Under the spreading chestnut tree." -- George Orwell, 1984 (1949)

But already in the eighteenth century the golden age of the chestnut had reached its twilight. Esteeming land development over gleaning, the physiocrats encouraged the peasantry to till the soil rather than rely on the yearly chestnut harvest. The physiocrats thought chestnuts induced most intractable laziness. Indeed, François Quesnay and Victor Riqueti Mirabeau wondered whether chestnuts didn't completely undermine a man's industry. "To my knowledge, inhabitants of chestnut countries are nowhere friendly with work," they opined. What's more, because chestnuts fell outside any tax regime, and because their replacement with more productive plants seemed anything but imminent, no worthy citizens of the modern state would chestnut-loving peasants ever become; such status arrived only from "Government of Nature," that is, mastery of the land and its produce by use of harrow, hoe, yoke and plow.

Recipe for Chestnuts à l'Espagnole from The Cook's Dictionary (1833): "Take about fifty good chestnuts, and blanch them in hot water, in the same way as almonds; when they are thoroughly cleared of both skins, put them into a saucepan, with two ounces of butter, four large spoonsful of espagnole, two glasses of consommé, a bay leaf, and a little nutmeg; boil the chestnuts in this for half an hour, then take them out, and having strained, keep them hot in the bain-maire, while the sauce is reduced; then pour the latter into a dish, lay the chestnuts on it, and serve."

In North America the chestnut's costliness is partly due to a chestnut blight accidentally introduced around 1900 by imported Japanese chestnut nursery stock. Within forty years the four billion–strong American chestnut population was devastated.

Government of Nature nonetheless prevailed, though maybe not as its champions envisioned, thanks to a few hard winters, changes in culinary fashion, and the growing popularity of wheat as a cheap and easily obtained food. The chestnut meanwhile declined in popularity as well as abundance. Today its relative scarcity means that it fetches a higher price per pound than beef. Once considered "sweet mucilage" of the poor, this modest nut now serves merely to bind the reasonably affluent to their holiday traditions.

Though free for the taking, chestnuts exacted a price for doing so. Nasty, back-breaking business, the harvest lasted as long as three weeks (chestnuts do not fall all at once). After gathering them, harvesters had to free them from their burrs, a task that roughened hands and tempers. Those who husked without complaint won recognition as "chestnutters," this name reflecting their fellows' esteem. Yet even harvesters so distinguished did not escape the task that followed: boiling the freed nuts to loosen their bitter and astringent skin. Peeling chestnuts harvesters usually did before a fire, which warmed them as they worked long into the winter evenings. To peel five pounds of raw chestnuts took nearly an hour, which meant that a family of five could look forward to three hours of such work -- and this simply to prepare enough to feed themselves. The drudgery of the chestnut harvest nonetheless failed to deter people from gathering what they considered manna from heaven. Free had a flavor all its own, they reasoned, a flavor sweet enough to dispel the bitterness of toil.

Though free for the taking, chestnuts exacted a price for doing so. Nasty, back-breaking business, the harvest lasted as long as three weeks (chestnuts do not fall all at once). After gathering them, harvesters had to free them from their burrs, a task that roughened hands and tempers. Those who husked without complaint won recognition as "chestnutters," this name reflecting their fellows' esteem. Yet even harvesters so distinguished did not escape the task that followed: boiling the freed nuts to loosen their bitter and astringent skin. Peeling chestnuts harvesters usually did before a fire, which warmed them as they worked long into the winter evenings. To peel five pounds of raw chestnuts took nearly an hour, which meant that a family of five could look forward to three hours of such work -- and this simply to prepare enough to feed themselves. The drudgery of the chestnut harvest nonetheless failed to deter people from gathering what they considered manna from heaven. Free had a flavor all its own, they reasoned, a flavor sweet enough to dispel the bitterness of toil.