In an interview a few years ago, Norman Rush was talking about the ways he was influenced by African writers, and he mentioned that “No non-African could do what Achebe has done.” And I get what he was saying. But there’s also a back-handedness to this compliment that makes me nervous. Here’s the thing: Achebe was just a great writer, full stop. I’m not sure anyone could do what he did. And while it may seem like a small point, like complaining that a genuine compliment just isn’t enough of a compliment, there’s an important point of which it’s in service, a larger issue of who gets to “know” what sorts of knowledges and why. It diminishes his achievement to pretend that white writers don’t write about the things he wrote about, because if Rush’s novels (or any post-war white novelist) had to be placed next to Achebe’s, we might have to acknowledge the uncomfortable fact that the best practitioner of English literature might be an African.

I am certainly not suggesting we treat novel-writing like a foot race. But there are those who certainly do think of literature as a kind of olympic sport, and for “our” writers to share the same field with “their” writers would be as calamitous as for a black pitcher to throw to a white batter in baseball’s pre-Jackie Robinson era. He might strike him out, after all (or, more complexly, he might not). So, as a result, we get separate events for “race” or “cultural” writers, distinct and cordoned off from the more universal concerns of real writers. And, as widely read as Achebe is, it always irks me that people so rarely revere him in the way that I think he should be revered. I may seem to be making the banal request that people should revere him more, I’m not, not really; I’m saying we should revere him better, doing so for better reasons.

Things Fall Apart, for example, is a very deceptively simple book, and I suspect this apparent simplicity deceives the vast majority of his readers. Okonkwo may be a man who never let thinking get in the way of whatever he wanted to do, but his puppetmaster’s seemingly uncrafted and naïve narration is as tightly plotted and structured as the Greek dramaturgy it both tropes on and defies. It may seem to be the simple story of a man and his destiny, a simply redemptive vision of a romantic lifestyle wiped out by colonialism and a condemnation of the colonialists that did it, but part of its magnificence as a piece of writing is that it manages to be all of this without disturbing its ability to also be about the ways that culture gets politicized, the way that traditionalism manages to express (and, dare I say, sublate) deeper and less coherent political anxieties and desires, particularly different modes of gender practice. And it’s a novel which enacts these conflicting desires with a certain magnificent disdain for resolving them, or moralizing on them. So much of what Okonkwo does gets moralized upon in such spectacularly unsuccessful ways that one can (I would argue) understand Okonkwo only by deferring judgment of him, like a particle in a parable on Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. The plot hinges on why Okonkwo kills his stepson, but that act is also the novel’s black box; one can offer any number of explanations for Okonkwo’s act (and the consequences which it provokes in the style of Greek tragedy), but the novel does everything in its power to illustrate the ultimate unknowability of that origination, until one is left only to reflect on the ways that Okonkwo’s unknowability gets known, the ways that fictive truths take the place of a true truth eternally deferred. Precisely because the author refuses to authoritatively know Okonkwo, the novel has a profound and complex double-life, a narrative given shape by the absence at its center.

The simple point is simply that Achebe is not anything but a peer of “great” writers. And of course Rush didn’t deny that. But there is, hidden in the nest of assumptions out of which his aside slithered, a particular claim for the proper spheres inhabited by white writers and the proper sphere inhabited by Africans: what an African knows, a white person cannot, and vice versa. To say that only an African could write what Achebe wrote is to excuse himself for not having done so, and to claim his own little piece of the rock, the white person novel.

Who would waste their breath in asserting that only a white person could really understand what it means to be white? I think of the mystifications of the title character in Esk’ia Mphaphlele’s “Mrs. Plum” as an example of how the eyes of non-white characters (and authors) show us “whiteness” in all its glory. Sometimes those who live outside your world understand you in a way you don’t understand yourself, and this is as important a part of identity as the kind of claims made by a “race” writer. It is largely a white fiction that only Africans can understand Africa, and so too is Rush’s space-clearing gesture for himself a popular kind of white privilege within “African letters”: he is happy to be shielded from competition, to be awarded a tiny, but comfortable corner in which to sit. Rush is as much a race writer in this sense as Achebe. But while Achebe was canny enough to realize that white people were quick to extend him the benefit of the doubt with regards to his subject (being African, he must surely know Africans), he was also aware that he hardly deserved that credit, and made something powerful out of that realization. What, after all, did a Christian-educated Nigerian of the mid-twentieth century really know about the inner life of a late nineteenth century Igbo warrior, a man who never lived to hear the word Nigeria? And so, instead of eliding that knowledge, he built a magnificent literary edifice on top of it. Instead of donning the victory wreath he was awarded for a game he was too good to play, he proclaimed that the center was hollow, and would not hold.

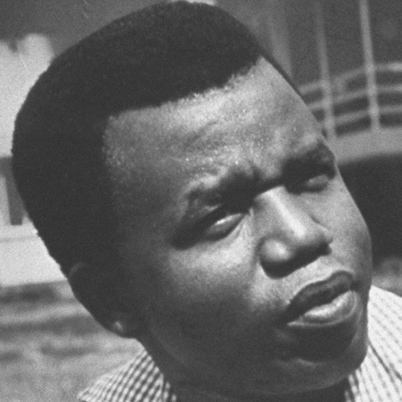

(originally posted on zunguzungu, 2008. Chinua Achebe, 1930-2013, RIP)