The following is a guest post by Jack Hamilton.

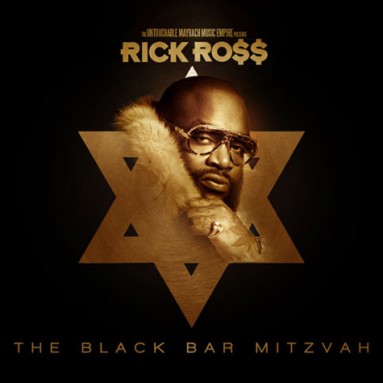

Earlier this week the prolific Miami-based rapper Rick Ross released his latest mixtape, pictured above. From a purely musical standpoint it’s pretty good in the way that a lot of Rick Ross’ stuff is good: lively, consistent, generally bereft of risk. But evaluating anything Rick Ross does from “a purely musical standpoint” is a little like evaluating Star Wars based on Chewbacca’s acting technique: Rick Ross isn’t so much a musician as a constellation of interconnected ideas, an concept album in human form. And when that concept album suddenly boasts the title The Black Bar Mitzvah and a cover that scans like Choose Your Own Adventure: Overdetermined Signifier, well, it’s best to begin from the beginning.

Rick Ross (pronounced RICK RO$$) was born William Leonard Roberts, taking his professional handle from legendary cocaine trafficker “Freeway” Rick Ross. His musical breakthrough came in 2006 with “Hustlin’,” a smash that firmly established Ross’ two exclusive fields of interest: narcotics, and spoils accumulated from selling them. He was forced to briefly but spectacularly break character when photographic evidence emerged that William Leonard Roberts—in stark contrast to his pseudonymous namesake, and persona—had worked as a correctional officer before entering the rap game. This revelation, remarkably for a genre in which snitches reputedly get stitches, did not derail Rick Ross, and may in fact have made him more appealing. “Rick Ross,” wrote Grantland’s Alex Pappademas this past summer, “was just like us, in that he was not exactly Rick Ross.” He remains appealing, outlandishly so—there’s an irrepressible charm to a man who rocks a chain of his own likeness, inspires photoshops like this, and lavishes his work with hubristic titles like Deeper Than Rap, God Forgives, I Don’t, and Rich Forever.

And now there’s The Black Bar Mitzvah, a project that’s suitably outlandish in whatever the hell it’s trying to do: the question is whether that thing is wildly offensive, transcendentally progressive or, somehow, both. To pick just one point of entry, start with the long and tortuously complicated history of African American and Jewish showbiz relations. As historian Michael Rogin argued, in Vaudeville and early Hollywood blackface minstrelsy was a dominant medium through which Jewish immigrant entertainers transitioned into the mainstream, forging Americanness through that most American of pastimes: racism. Here we have a black music magnate popping out from a Star of David in an image that seems to slap Al Jolson across the face while simultaneously high-fiving him, a top-shelf niche cocktail of revenge and reconciliation.

Alternately there’s a more troublesome suspicion that it’s just another iteration of a longstanding elision between Jewishness and wealth, a noxious and destructive stereotype that spans continents and millennia. The Black Bar Mitzvah is certainly playing on a cultural understanding of bar mitzvahs as sites of accumulation, which at the very least is a blasé trivialization or a sacred religious rite. Maybe it’s an homage to the considerable history of Jewish contributions to hip-hop: it’s impossible to imagine the past thirty years of hip-hop without Ad-Rock, Rick Rubin, or Lyor Cohen, to name just three prominent examples among countless others. Or a strategic inversion, even—after all, rap is famous for its subversive reappropriations of anti-black racism—which would in turn raise the issue: can subversively reappropriate a racist stereotype of a group one doesn’t belong to?

I don’t ask these questions rhetorically, and I’m sure they’re going away, as Black Bar Mitzvah is hardly happening in a vacuum. Rick Ross didn’t even coin the phrase: Jay-Z’s used it previously, and earlier this year Drake—a mixed-race Canadian MC who was raised Jewish, actually got “re-bar mitzvah’d” and used the occasion to film a music video. I spoke with Eitan Kensky, a cultural critic and Yiddish instructor at Harvard, about Ross’ latest. “The first thing that jumped out at me was, is this a thing?” says Kensky. “I’m not sure what to make of it other than to say it’s a great piece of cover art, and a clever way to normalize Drake’s Jewishness within a hip-hop context. But I'm hoping that it actually becomes a thing, like Jewish Christmas, a parallel tradition for those left out of the main culture.”

One also wonders whether if who’s Jewish/whose bar mitzvah question might be a red herring obscuring a more provocative question: in 2012, whose hip-hop is whose hip-hop, or, who’s hip-hop? The RICK RO$$ness of William Leonard Roberts suggests that rap might have finally entered a post-authenticity moment, or at least that its parameters of who’s “real” and who’s not are generously expanding. The genre has always had purveyors of slippery identities (Kool Keith, MF Doom), but they mostly kept to their own corners of the sandbox, away from the mainstream. The past few years have seen Lil Wayne delve into rock music and skateboarding (poorly, but no matter), while Kanye West and Drake have pioneered the sort of emo navelgazing usually reserved the acoustic-guitar-and-coffee-house set. The off-kilter styles of Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All—an collective whose relationship to the “authentic” is as opaque as its name—garnered lucrative record contracts and the attention of The New Yorker. Most notably, this past summer Frank Ocean—a singer with ties to OFWGTKA, Jay-Z and others—wrote eloquently and powerfully about falling in love with another man, making him the highest-profile artist associated with hip-hop to publicly identify as something other than strictly heterosexual.

To remotely compare Rick Ross’ Black Bar Mitzvah to Ocean’s coming out would be ridiculously stupid: the latter was an act of supreme courage, while the former is, at best, a modestly clever and totally weird inversion of any number of cultural stereotypes that ought to have died out long ago. As someone who’s neither black nor Jewish I have no idea whether I’m remotely qualified to speak on any of this, although given the complete clusterfuck of identity and authenticity that Black Bar Mitzvah presents I’m not entirely sure that anyone else is, either. But these are concept that deserve fluidity and too often ossify, and if it takes some RICK RO$$-style clusterfucking to loosen them up then that’s everyone’s black bar mitzvah gelt.