There may have been gold in "them thar hills," but there wasn't much to eat

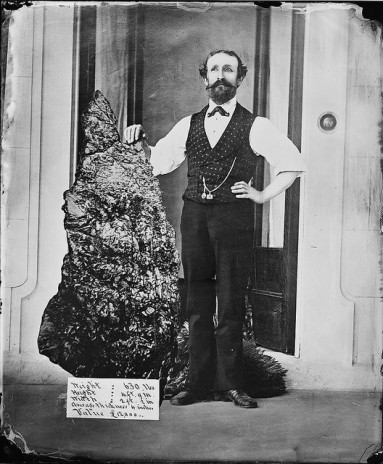

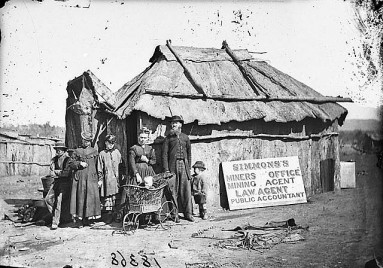

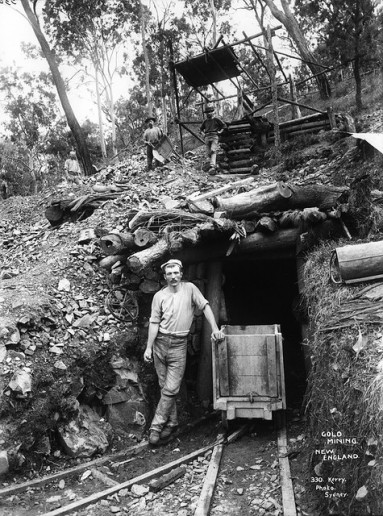

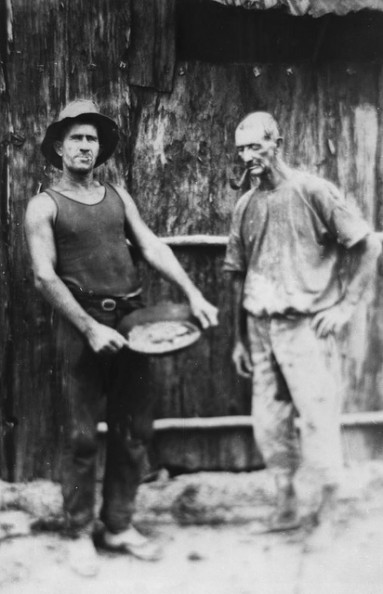

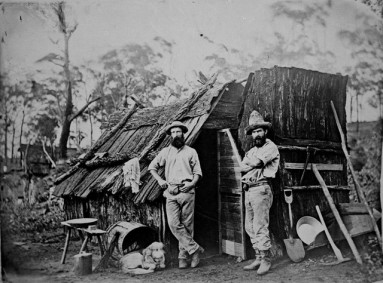

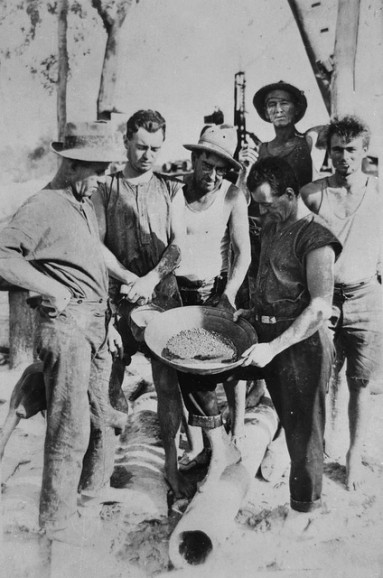

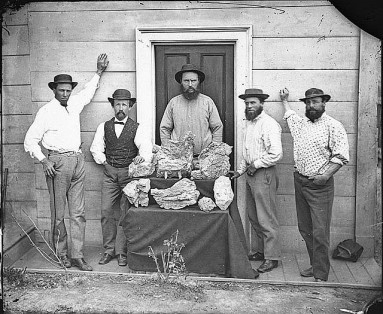

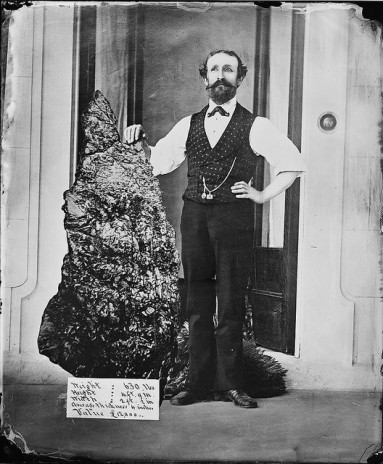

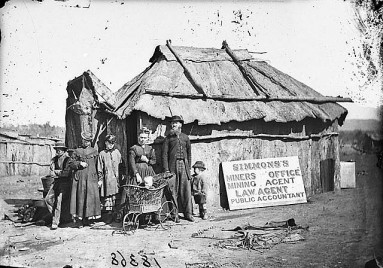

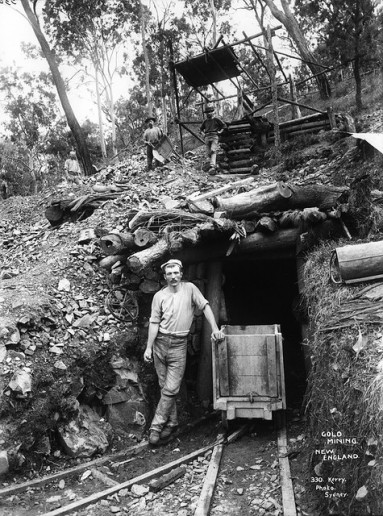

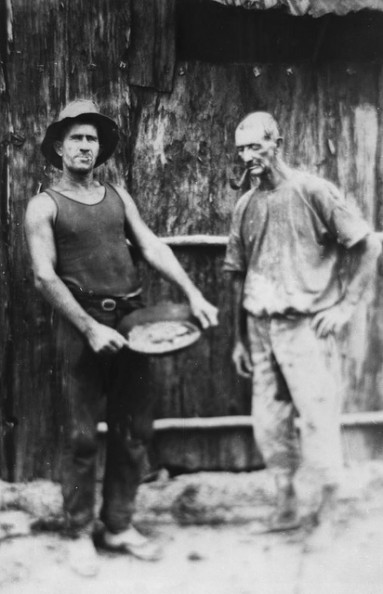

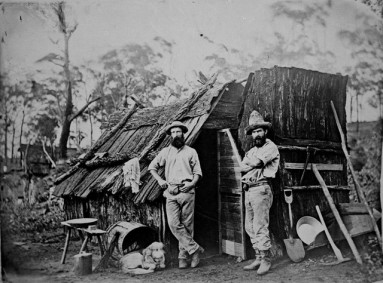

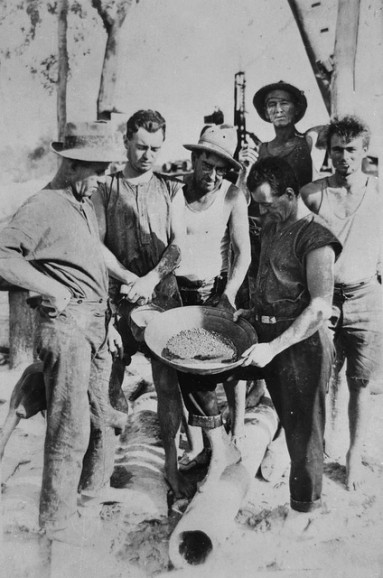

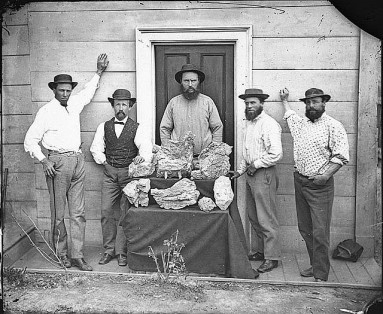

Photographs of scenes from various gold rushes, 1860-1930

"Amid these dark and dismal scenes, / I've struggled with an adverse fate, / And lived, ah me! on pork and beans." --from "The Miner's Lament" (1871)

Lewis Manly wanted nothing more than to be back at the dinner table in his father's Michigan home, a heaping plate of beans and bread before him. It was the winter of 1849. For weeks he had been traveling through the Great Basin Desert, "the most wonderful picture of grand desolation one could ever see," as he later described it. He had run out of food and water, and was lost besides. He could see nothing but salt-encrusted flats and low, black mountain ranges for miles around. Alkali dust filled the air. "Here was I," he lamented, "away out in the center of the Great American Desert, with an empty stomach and a dry and parched throat, and clothes fast wearing out... It was a darker and gloomier day than I had ever known it could be, and alone I wept aloud, for I believed I could see the future, and the results were bitter to contemplate."

The future was less bitter than Manly supposed. From the great desert he eventually escaped into the green fields west of the Sierra Nevada, where he joined thousands of men and women in searching for gold.

"If more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world." --J.R.R. Tolkien

Gold fever had a leveling influence. Miner Alonzo Delano mentions having often seen "the scholar and the scientific man, the ex-judge, the ex-member of Congress" engaging in the drudgery of the camps.

In

1848 gold fever became something of an epidemic. "Husband and wife were both packing up; the blacksmith has dropped his hammer, the carpenter his plane, the mason his trowel, the baker his loaf, the tapster his bottle," observed Reverend Walter Colton in the early days of the great California gold rush. "All are off for the mines, some on horses, some in carts, some on crutches and one went in a litter." Along the way these "Argonauts," as prospectors were called, encountered bandits and wild animals. They had to navigate steep mountain passes, ford rivers, and, once their provisions dwindled, hunt game. For many of these men and women, the overland journey to the mining camps was their first taste of the great outdoors.

In the winter of 1931 a group of archaeologists hiking in Arizona's Superstition Mountains discovered a human skull. Two bullet holes -- one small, the other large -- were evident, suggesting that whoever killed the man shot him point blank. Not far from where the skull had been found were scattered human bones. Among them lay a checkbook. In it were written directions to the fabled Lost Dutchman Mine. Below these appeared the cryptic phrase, "Veni, vidi, vici."

Rumors of wealth ripe for the taking drew Argonauts from places as far away as China and Germany, perils of the great outdoors notwithstanding. They had read of a San Francisco newspaperman who had run along Montgomery Street, two quinine bottles stuffed with nuggets in hand, and of a prospector who panned some $75,000 worth of gold from a riverbed. Word had it that these fortunate fellows feasted on caviar and oysters, bonbons and bear steaks, which they washed down with champagne in restaurants that rivaled the East coast's finest. Whether fact or fiction, these reports weaved a heady spell: The first five months of 1849 saw 17,661 people pass through the Ft. Laramie, Wyoming way station as they journeyed west.

"Mining rushes are eccentric, erratic and epidemic," noted J.M. Gunn in 1898. "They break out in unlikely places when least expected, become contagious, then disappear as suddenly as they came."

Many came to learn that these riches were no easy pickings

. Prospecting proved hard work. Burdened by shovels and other tools, prospectors stood hip-deep in water for hours on end, their daily recompense often amounting to only a few flakes. Some used heavy cradles, oblong-shaped wooden boxes about three-feet long and set on rockers, while others preferred troughs called Long Toms. Whatever their equipment, it was inevitably heavy and liable to strain muscles, wrench joints, and chafe skin. One miner complained that his friend suffered "a sort of felon on his hand caused by rubbing on the cradle," while he himself struggled with a "lame back." Sand fleas compounded the discomfort. These noxious insects, which "filled the air like dust," bit prospectors as they toiled, leaving uncomfortable welts. Indeed, rarer than a mother lode was a prospector who boasted no injury.

"It has been said that the gold rush made Seattle, and I truly believe it. But I shudder to think of the cost in human life and misery. During the gold rush that western city was more wicked than Sodom; the devil reigned supreme." --Arthur Arnold Dietz, Mad Rush for Gold in Frozen North (1914)

"I was just like a child with money: I flung it away with a curse, / Feasting a fawning parasite, or glutting a harlot's purse, / Then back to the woods repentant, back to the mill or the mine, / I, the worker of workers, everything in my line." --Robert William Service, "The Song of the Wage-Slave" (1908)

"All Fool's Day, and most of the fools are here." --Louie B. May, the Chikoot Trail, April 1, 1898

Injured and bug-bit prospectors dragging themselves home faced further ordeal. Found at the bottom of deep riverbeds and ravines, mired in mud and strewn with trash, mining camps were miserable places, the names they bore -- Bedbug, Poverty Flat, Gouge Eye, Delirium Tremens -- attesting to their conditions. One prospector described his camp as a veritable midden of "old boots, hats, and shirts, old sardine-boxes, empty tins of preserved oysters, empty bottles, worn-out pots and kettles, old ham-bones, broken picks and shovels." Atop such refuse prospectors pitched their tents and slept. They washed their clothes in a river's rank eddies; their meals they fixed on small sheet-metal stoves or over smoky greenwood fires.

"'Flapjacks?' enunciated one laboriously; 'flapjacks? Why, my fren', you don't know nothin' about flapjacks. I grant you," said he, laying one hand on the other's arm, 'I grant ye that maybe, maybe, mind you, you may know about mixin' flapjacks, and even about cookin' flapjacks. But wha' do you know about flippin' flapjacks?'" --from Stewart Edward White's Gold (1913)

In 1849, A.C. Ferris of New Jersey made the 114-day journey from New York to San Francisco on the brig Cayuga. The ship's supply of Mexican jerked beef, "sold by the yard," was so tough and salty, Ferris wrote, that he found it necessary "to attach it to ropes and tow it in the sea for forty-eight hours before any attempt could be made either to cook it or eat it without cooking." But no one complained, Ferris added, because their heads teemed with dreams of the "enticing glitter of the yellow gold in the mines of California."

These meals left much to be desired. Though a lucky few did dine on oysters and sundry delicacies, the majority had to content themselves with potatoes, meal, dried pork, molasses, and coffee. Eaten day in and day out, this diet often inflamed eyes, bloodied gums, and blackened legs -- all symptoms of scurvy.

Yet even this limited bill of fare was preferable to the food prospectors ate when their supplies ran low, as often happened in some of the more remote camps. "I am too weak to attempt traveling," California prospector Joseph Bruff wrote after having exhausted his grub stake. "Maybe I can shoot a bird." This he attempted to do and, after one or two errant volleys, finally managed to bring down "a very poor and tough blue-bird, about the size of a brown sparrow." Bruff then hunted up "2 old dirty flour-sacks," which he scraped to get "2 ounces of very mixed compound -- of dark & yellow lump & cakes of sour flour, hairs, cotton lint, & additions the mice had made." Removing what he could of the mice's additions, he mixed sour flour and bluebird together in a kind of soup. A few days later starving again, he caught sight of "the fresh tracks of an Indian." "Oh! if I can only overtake him!," Bruff mused, "Then I will have one hearty meal!" To those who might think him bloody-minded Bruff plead cruel necessity. "I have heard how people would starve to death rather than eat human flesh! Fools! How little could they form an idea of the cravings of hunger! ... My mouth fairly watered, for a piece of Indian to broil!"

"The desire of gold is not for gold. It is for the means of freedom and benefit." --Ralph Waldo Emerson

Though few prospectors went to the extreme that Bruff contemplated, they did commit other crimes, jumping claims, stealing crops, looting homes, ransacking farms, destroying roads, and killing livestock when it suited them. Wherever they went they left their mark.

Recipe for raccoon from Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings (1853): "First catch your coon and kill him, skin him, and take out the entrails; cut off his head, which [you] throw away; then if you have water to spare, wash the carcass clean. Parboil an hour, then roast it before the fire on a stick. While it is roasting, walk ten miles, fasting, to get an appetite, then tear it to pieces with your fingers and it will relish admirable, with a little salt and pepper, if you happen to have them."

"People looked on my property as their own," complained John Sutter, the hapless sawmill owner whose gold-rich land became ground zero for the California rush. "I was alone and there was no law."

Many shared Sutter's complaint, but little could be done in the face of such zeal. The decades preceding the rush had seen tremendous economic and social change, more so than after the Civil War. For many of the miners the gold rush offered the only escape from the competition, chronic unemployment, low pay, and incessant boom-and-bust cycles that had come to characterize American life. Gold raised the standard behind which marched countless strivers facing otherwise limited prospects. Some marched to their fortune, some to their doom.