I began the Dinner series in 2016 with "Dinner with Caligula." Much to my shock and sorrow, Caligula did show up to dinner. But history did not end with Caligula, so neither will this series.

On weekend nights I’ll sometimes stream Check, Please! a show—really a show template—in which local PBS affiliates invite viewers to discuss their favorite area restaurants. Each participant in turn dines at the restaurants recommended by her fellows and then offers her impressions of her dining experience. More than simply a sampling of local dining possibilities, Check, Please! offers a glimpse of quaint regional differences that corporate-media monoculture hasn’t quite managed to erase. Watch enough episodes and you’ll learn that people in Kansas City rate value, which usually means piles of meat at a nice price, as highly as they do flavors and ambiance. Folks in Phoenix, meanwhile, appear to prefer any cuisine, be it French, Spanish, Creole, or Croatian, that makes them forget they’re in Phoenix. And no matter what eatery they choose or have chosen for them, Chicagoans seem anxious to come off as worldly and refined as New Yorkers.

You also learn a lot about motivations for dining out, and this makes Check, Please! something of a casual study of the way we live now. None of them are surprising. They come down to convenience or entertainment. Where the first represents a bid to save time, the second represents a bid to spend it in interesting ways. Yet beyond these lay a documentary impulse, fairly summed up by one Check, Please! Chicago participant: “If it’s not Instagrammable, it’s not worth eating.”

That dishes be photogenic as well as filling and flavorful seems a strange sentiment for anyone who resists absorption in social media. Yet the “new economy” and the technology undergirding it has bred unwonted forms of value perception. Dining out, once a private pleasure, has become a public performance, albeit not for the entertainment of other diners in the restaurant, who no doubt are too busy staging their own performances to notice or care.

It exists rather for the benefit for an unseen yet vocal chorus whose replies bolster the aura of prestige the diner seeks to conjure. At stake in all this is the diner's standing. In this sense, the impulse behind “‘gramming” a meal differs little from the urge felt by the minor medieval lord who serves an enormous pie of four-and-twenty blackbirds to retainers otherwise eager to overthrow him, or the Victorian matron whose fears of bankruptcy and social disgrace she channels into making multihued jellies and tottering towers of imported fruit. Such displays alike betoken a will to personal security and belonging, no matter how chimerical those states might be.

Gustatory display simply isn’t indulged in by people who feel their lives are secure. It is peculiar to societies that make little provision for citizens who may have lost their fortunes or the ability to make those fortunes anew. Sustain such a loss and you might as well die. (And, indeed, from disease, alcoholism, neglect or one of the many consequences of despair, many did die.) Ostentation in dining suggests that you live well and therefore deserve to live--and your Instagram followers need never know that you may not make next month’s rent and your student loans are in default.

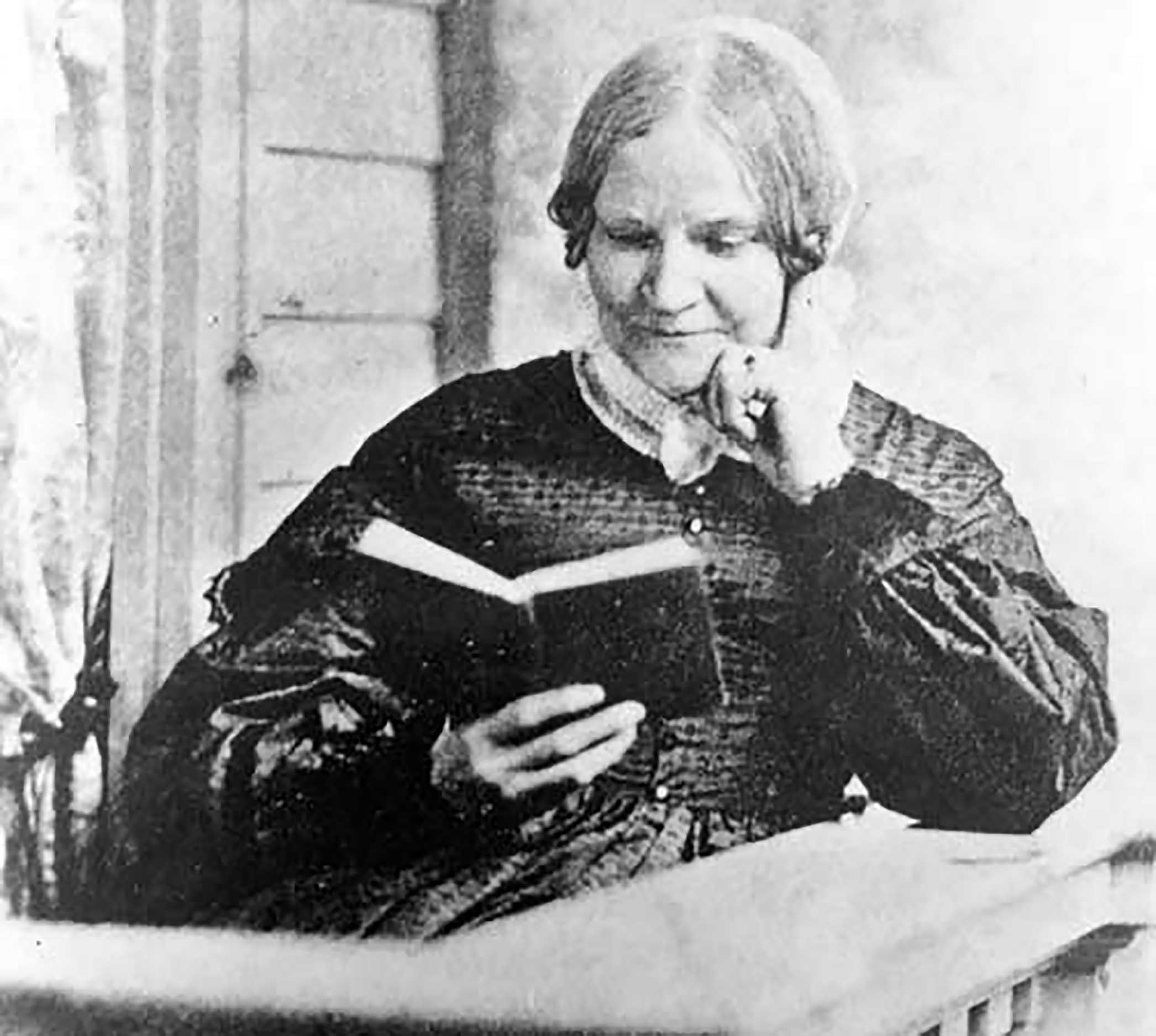

Nineteenth-century American writer Lydia Maria Child considered foolish and wasteful attempts to appear to live high on the hog when really the wolves were at the door. Rather than aping their betters, she believed, those of modest means ought to cultivate canniness and wisdom in service to the cause of justice and equality. Frivolous getting and spending betokened a fecklessness antithetical to the supposed values of the American republic. The only way to ensure the survival of those values was to become as independent as possible from a market that depended upon—and helped to create—the gap between rich and poor.

Child herself enjoyed little opportunity to engage in feckless consumerism. Born the last of five children in Medford, Massachusetts in 1802, she spent much of her childhood alone and ignored. Her father, a baker by trade, spent most of his time turning out the famous Medford crackers that could be found on most seafaring vessels of the time, and her mother, owing to frequent illness, resented having to care for a small child. Left to her own devices, Child borrowed books from a precocious older brother and spent her days absorbed in Shakespeare, a pastime that met with disapproval from her parents, practical Protestants they were.

As she read of the exploits of Henry IV and Prince Hamlet, the world around her was changing rapidly. By the time she was 17 years old, the United States had entered its first recession and banking crisis. Trade declined, manufacturers went bankrupt. Yet industrialization continued apace, flooding shops and markets with cheap manufactured goods. Masters of trades, men and women alike, found that where factories hadn’t driven them out of the market, their apprentices had. The combined pressure thus drove them from their shops into the dreary world of waged labor. Advances in agricultural technology similarly thinned the ranks of farmers. Though per capita income doubled between 1820 and 1860, the divide between the country's wealthiest and poorest citizens widened, the growth favoring the monied and propertied classes. By 1840 the richest five percent of free males owned 70 percent of the real and personal property. That year also saw the birth of a new word to describe a member of the uppermost of that upper crust: “millionaire.” (To be worth $1 million in 1840 was equivalent to being worth $28 million today.) And at the other end was the greatest economic inequality of all: the “peculiar institution” of slavery in the American south and the thousands of men and women who toiled in that condition.

The economic and social ferment became a rich subject for writers. So great was the demand for literature on it that American authors could earn a living with their pens for the first time. Grown into a fiercely independent and intellectual woman, Child was one of the first women to take up the occupation, despite the perception, prevalent at the time, that “no woman could expect to be regarded as a lady after she had written a book.” In 1824, she self-published Hobomok, raising the $495 (about $11,500 in today’s money) in funds herself. An account of the life and deeds of a Puritan woman who marries a Native American, it sold poorly, possibly as a consequence of its controversial matter. Its author begged a favor of the prominent Harvard literature professor George Ticknor. Exercise of his “influence in the literary and fashionable world” did cause sales of her “unfortunate book” to pick up, and she found herself “a little wee bit of a lion” in Boston literary society. She received gifts and invitations to lavish dinners. On one occasion General Lafayette, the French hero of the American revolution, stooped to kiss her hand.

Fame failed to breed in Child a desire for higher station. Though she had written a fairly popular novel and experienced success with other literary ventures, she understood that wealth was fleeting. She also knew she wanted to devote herself to causes that would likely prove unpopular and therefore not terribly remunerative. Modest living meant the freedom to follow her conscience without going broke. The know-how she gathered along the way she eventually distilled into book form, publishing in 1829 The American Frugal Housewife, a slim volume dedicated, as she writes, “to those who are not ashamed of Economy.” “Books of this kind have usually been written for the wealthy,” Child notes in the book’s introduction. “I have written for the poor.”

Unlike earlier cookbooks, whose elaborate recipes assumed the availability of plenty of servants, American Frugal Housewife features dishes that may be prepared by women alone at home, be they young brides keeping house far from family and friends or widows dependent on tightfisted relations. They might also be women like Child herself—self-supporting writers devoted to ending slavery, racism, economic injustice, and the denigration of women.

The simple and nourishing, yet varied, recipes in American Frugal Housewife include those for beef tea and milk porridges, broiled tripe, spiced souse, curried fowl, puddings (baked, boiled and steamed), pies of mince, pumpkin, cherries, whortleberries. There are other sweets besides—cupcakes, tea cakes, and election cakes—and even drink: spirited beer of hops and molasses and potatoes, for example.

Along with recipes Child's book offers culinary tips and tricks. Rose leaves steeped in brandy makes for an infusion “pleasanter than rose-water.” Similarly, a brandy and peach leaf infusion imparts a nice flavoring of custard and pudding. She deems a “profitable thing to buy” and counsels that a mackerel’s belly, when pinched, should never give “like a bladder half filled with wind” but should be “hard like butter.”

The tips and tricks in American Frugal Housewife extend to medical and sundry household concerns. Some advice strikes modern readers as odd: bear’s grease for croup, ear wax for chapped lips, and a “good quantity of old cheese” for a stomachache. A solution of water, glue, and skim milk restores Italian crape, and lime water preserves eggs. Pokeweed kills cockroaches; mercury, bedbugs. But some advice is eminently sensible, even by today’s standards. Brush your teeth before bed and change your bedsheets once a week. And avoid traveling simply because you've found a cheap opportunity to do so. (Wisdom that citizens of Barcelona and other totally Airbnb-ified locales would no doubt endorse.)

American Frugal Housewife contains all necessary knowledge about nineteen-century domestic economy. But Child didn’t mean for penny-pinching to be carried out in the name of avarice or miserliness. “True economy is a careful treasurer in the service of benevolence,” she writes: “and where they are united, respectability, prosperity and peace will follow.” Child’s brand of frugality existed for the nobler end of building a just and equitable nation, one that had rejected the excessive and mindless consumption of the European elites. “A republic without industry, economy, and integrity, is Samson shorn of his locks,” she noted. Consumption must be mindful and prudent; anything else invites a return to the Bad Old Days.

Some failed to see the nobility of that end. They judged her focus on frugality as vulgar. Author and editor Nathaniel Willis, an old friend of Child’s, panned American Frugal Housewife for, as he wrote, its “thorough-going, unhesitating, cordial freedom from taste.” His proved to be a minority opinion, however, if popularity is any indication. Child’s landmark book went through twelve reprintings in three years and eventually 30 editions.

The wisdom she dispensed stood her in good stead in the succeeding decades. In 1833, she published the abolitionist tract “Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans” in which she enumerated the evils of slavery and called for advancing “the inevitable progress of truth and justice.” Few heeded this call, and many denounced it. Friends snubbed her. The public stopped buying her novels and magazine. Members of the library where she did her research told her she was no longer welcome there. A prominent lawyer showed his disgust by picking up a copy of Child’s tract with a pair of tongs and throwing it out a window. But she believed steadfastly that “if the Union cannot be preserved without crime, it is eternal truth nothing good can be preserved by crime.”

Child herself preserved equanimity enough to continue writing in service to her cherished causes. In 1835 she published The History of the Condition of Women, in Various Ages and Nations. Her findings therein led her to conclude that those countries prospered which allowed women to develop and apply their talents. And in 1843 she begin a series for the prominent abolitionist magazine, the National Anti-Slavery Standard, whose editor she had become three years prior. The series consisted of accounts of her wandering the streets of New York. She visited the Tombs, the city’s fearsome prison, and red-light districts, all the while gathering stories of racial, economic, and sexual injustice. (Child’s field writings were an early example of a “city column,” which would become a staple feature of urban newspapers throughout the U.S.) Crime, she believed, was caused by poverty. If society did more to help the impoverished, most crime would disappear. When will men learn that “society makes and cherishes the very crimes it so fiercely punishes,” she wondered in one installment, “and in punishing reproduces?”

Though Child continued to write on society’s ills, she never regained the fame and notoriety she had achieved before publication of her Appeal. Her personal life certainly put her on no certain footing to do so. She moved from rented room to rented room, thanks to her husband’s chronic unemployment and unsound financial sense. More than once liquidations left her with virtually no possessions, forcing her to rebuild households from scratch. In her circumstances she found sympathy from the poet John Greenleaf Whittier, who observed that no woman more than Child had suffered for her conscience.

As Child saw it, her suffering mattered little. By the time she died her dream of abolition had come to pass—an apparent vindication of her message of principled frugality. She nonetheless knew that the great work remained unfinished. For Child, the American republic promised all people a right to life, liberty, and property; so long as it failed to make good that promise, it was no republic at all. “The United States is a warning ... rather than an example to the world,” Child wrote. The task was to become the example.

Many of the injustices of Child’s time have survived into our own. Getting from warning to example may not make for many Instagrammable moments. Then again, there’s no need for selfies at a table that can seat everyone.

Recipe for Caraway Cakes from The American Frugal Housewife

Take one pound of flour, three quarters of a pound of sugar, half a pound of butter, a glass of rose-water, four eggs, and a half a tea-cup of caraway seed,—the materials well rubbed together and beat up. Drop them from a spoon on tin sheets, and bake them brown in rather a slow oven. Twenty minutes, or half an hour, is enough to bake them.