All photography is a record of a lost past. Photography does not share music’s ability to be fully remade each time it is presented, nor does it have film’s durational quality, in which the illusion of a present continuous tense is conjured. A photograph shows what was, and is no more. It registers in pixels or in print the quality and variety of light entering an aperture during a specific length of time. There are no instantaneous photographs: each must be exposed for a length of time, no matter how brief: in this sense, every photograph is a time-lapse image, and photography is necessarily an archival art.

There are certain oeuvres within the history of photography in which this archival pressure is felt more intensely than in others. Eugène Atget's facades, architectural ornaments, and street corners depicted a Paris that was, even while his work was ongoing, already passing away from view. Atget's images have a sense of speaking out from a buried visual subconscious, a sense aided by, but not wholly dependent on, the depopulated views he preferred and the melancholia of the sepia tone bestowed by time. The other part of the charge of the images comes from what we know about the places they depict: chiefly that those places are gone.

The same kind of embedded charge, that of evanescence caught on the wing, can be felt in all the photographs presented in Disappearing Shanghai, the new book by Howard French. French is a journalist of unusually broad expertise: he was Bureau Chief for the New York Times in several countries, and has had many years of experience reporting from Africa, the Caribbean, Central America, and Asia. His work as a photographer is less well-known: the selection in Disappearing Shanghai marks the first appearance of his photographs in book-form.

It might be assumed that French is one of those dilettantes who, unwilling to leave well enough alone, insist on dabbling in areas beyond their specialization: a writer of well-received books and articles turning his attention to something less taxing, something easy, like the occasional snapshot. But one hardly need look at more than three or four of his photographs to be disabused of this notion: there is much more going on in the images than hobbyism. The images, in fact, look like work. They indicate intent, thought, order. They provoke questioning, demanding from us what all good photographs do, which is that they be placed in some relation to the wider practice of photography and to the ethics and possibilities of the form.

Disappearing Shanghai is a visual account of five years worth of shooting in the rapidly changing backstreets, homes, and alleys of China’s largest city. The work originated during French's time living there as a Times reporter, and developed side-by-side with that work. The instinct that brought these images to the surface (it seems natural to think of them as having been submerged) was that of a flâneur. Around the time that French began to learn Chinese, he also started to go on long walks in the less glitzy areas of the city: the older areas, the more traditional areas, precisely those parts of the city that were beginning to be effaced by the economic boom. He began to take photos of the people he met. Soon, he was invited into their homes.

The photos that resulted are notably different from what we might ordinarily think of as photojournalism: they are dynamic, but they are not the action-packed singles of the kind that win photojournalism prizes. There is something far more patient at work in them. We feel that the photographer has not so much captured a "decisive moment" as gained us admission into private moments of long duration. Many of the images project the longueurs that are, after all, a substantial part of regular life: unhurried, unharried, the part of life that isn't caught up in working for pay, the part of life that is a simple, unfussy catalog of the passing minutes.

Many of the photos in Disappearing Shanghai rescue a peaceful time of day—just before lamplight—from the heart of one of the world's brashest and fastest-growing conurbations. These Chinese faces and selves bring to mind the work of another archivist of the passing scene, August Sander. In the work Sander produced around and just following the First World War, he created a catalog of images that stood in for an entire generation in Weimar Germany. Farmers, cooks, stevedores, teachers, priests, and manual laborers were all represented in their full dignity, and Sander achieved something like a double-portraiture in each case, because each actual individual was at the same time a representative type.

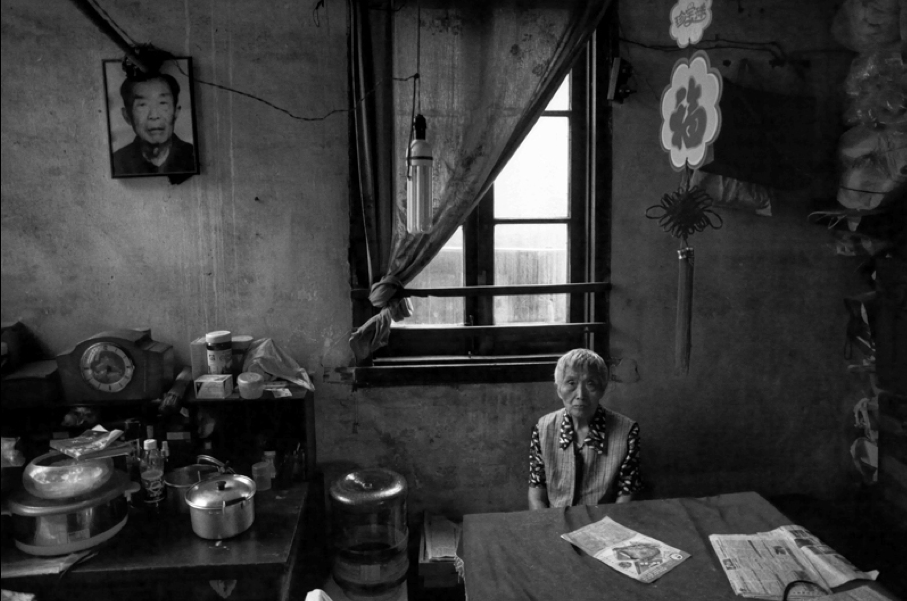

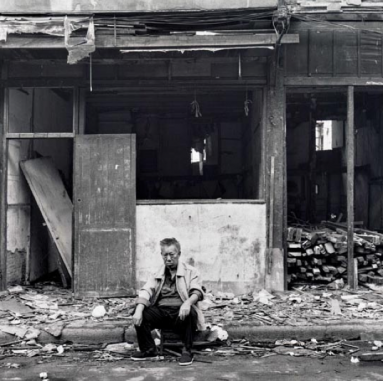

This ability to be at once universal and yet ineluctably particular made John Berger ask, of Sander's images, just what it was the photographer told each of his subjects that made them all believe him in the same way. In a related fashion, the portraits of Disappearing Shanghai show people as their real and undisguised selves, so that one almost suspects that French has brought each subject into his confidence in the same way, so that each is unable to be before the camera other than they are in the absence of the camera. At the same time, these are also photographs of people in a story, players on a stage about which they might only be faintly aware, and the story they tell is about a world that is passing, and will soon be past.

Regarding us are the denizens of a traditional urban neighborhood: the old man sitting down on the street and looking lost in front of a ruined building, a little boy sitting before a tricycle with his legs ostentatiously crossed, an infant unimpressed with the dinner his mother presents him. There are the exhilarating moments in which French has been granted admission into small, cluttered apartments: an old lady with an image of her ancestor (or perhaps it is her deceased husband) on the wall behind her; a couple seated on bunks, between whom an enormous silence looms. They are all there in their entirety, even though we do not know their names or speak their language. The photographer's lens introduces them. They are intact, quiet, complex. They have all believed him in the same way.

Howard French came to photography early, shooting Olympus SLRs while he was still in high school, and already in those years was working a darkroom built by his father. A signal event had occurred when he was younger, when he was a mere boy: he had seen a photograph someone had made of his younger brother. French recounts that he was astonished by this image, which seemed to contain not only his brother's appearance but also the entire context of sights, sounds, and emotions out of which the image was drawn: "It turned out to be one of the most revealing portraits I've seen, and even the summer heat, and Jamie's beading sweat, and an air of urgency, as if our mother had beckoned him to come home right away, or else, are all intensely palpable."

This description contains an honest love of the world of memories and experience (and strongly evokes one of Leonard Freed's photos of boys at play in the streets of New York). It is a sensibility at home in the layers of a moment, and in this early experience was sown the seed that would inspire French's later photography which went on to span several countries, notably in Africa and in Asia. He learned a great deal from watching his photojournalist colleagues, but his own wayward instincts were to become the dominant note. His system is footloose and unsystematic, and the images that result are as in love with the world of surfaces, persons, and places as the writings of Walter Benjamin or Walt Whitman were. French writes about the situations he encountered photographing Shanghai in a descriptive, inventorial passage that could have been lifted from Benjamin's memoir of Naples:

"...the songbirds and the crickets lovingly raised in their cages, the street markets and the foods, with their smells and colors that change so suddenly and so crisply according to the season, the eternal tending of laundry from long bamboo poles, the wildly screeching bicycle brakes, the lusty throat clearing, the world weary lounging about on beach chairs and in pajamas, the very appearance of the people's faces, weathered by a century of immense and often brutal change, like the old man in the faded Mao suit I saw on a street corner this afternoon looking for the life of him like an apparition lost amid the onrush of the new."

Within a decade of the invention of portrait photography, studios up and down Broadway offered ordinary people the possibility of preserving their own visages for a modest sum. In 1846, Whitman had a chance to see, in one of those studios ("Plumbe's Daguerreotype Establishment"), rows and rows of such faces, of persons unknown, persons that, he knew, would soon be part of a vanished world, of whom the only record might be those very pictures. He was stunned by this vibrant new form of sympathy with human life, and called it, in a marvelously apt phrase, an "immense phantom concourse."

The images in Disappearing Shanghai contain the same fine surprise. French's images are freed from the dramatic needs of a news report. With a quiet testimonial force similar to the photographs of Atget, they bring us the deeper drama of mundane life. The cumulative effect of the images, all taken in the same half dozen neighborhoods of the city, is of how rich the substance of human experience is, and how reliably it is to be found side-by-side with insubstantiality, with what is already passing, or possibly already past.

---

This essay is adapted from my introduction to Disappearing Shanghai: Photographs and Poems of an Intimate Way of Life, photographs by Howard W. French and poems by Qiu Xiaolong (Homa & Sekey Books, 2012.)