By Ann Foster

Four thousand years ago, hysterical suffocation was thought to be a result of women’s wombs wandering “restless” through the female body, wreaking havoc. The Greek word hysteria, after all, refers to the uterus. The first mention of the condition came during the 1602 trial of Elizabeth Jackson. Jackson stood accused of witchcraft after teenage Mary Glover was stricken by mysterious and violent fits following a series of altercations between the two. A physician named Edward Jorden chose to testify on Jackson’s behalf, presenting his argument that Glover was not a victim of witchcraft but, based on her symptoms of a swollen throat, violent fits, and periods of blindness, a victim of hysteria. Jorden, though, was unable to offer a treatment for Glover’s symptoms, which prompted the judge to decide against the existence of the syndrome and ultimately find Jackson guilty of witchcraft.

Advances in the fields of psychiatry, psychology, and gynecology swiftly did away with the understanding of hysteria as a medical condition by the mid-20th century, leading to the current definition of hysteria as an ungendered state of uncontrollable mania. But as we grapple with more women in the public eye, the sexist history of the word has come again to the fore. A group of many genders may be described as hysterical with few taking offense. But using the term to describe one specific woman leans into a misogynistic belief that women are helpless victims of their own biology, who act unpredictably and perhaps even dangerously.

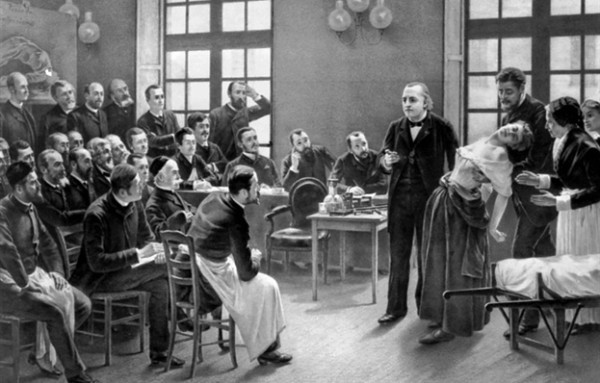

To do so discounts the real documented pain of those who suffered from hysteria pain, exacerbated by the torturous treatments and tests they were forced to undertake by a medical community eager to learn the parameters of their symptoms. The typical hysterical victim of this era was generally unmarried, often a woman with a history of outspoken or unconventional behavior. Women were not diagnosed as hysterical merely for acting outside of societal expectations, but that factor may certainly have affected the manner in which they were treated.

But as we grapple with more women in the public eye, the sexist history of the word has come again to the fore. A group of many genders may be described as hysterical with few taking offense. But using the term to describe one specific woman leans into a misogynistic belief that women are helpless victims of their own biology, who act unpredictably and perhaps even dangerously.

Medical science during the Medieval and Renaissance periods worked with a different balance than the Western philosophy that would develop in the 18th century. Rather than comparing a patient’s symptoms to a list of maladies and matching them to the closest fit, doctors dealt with each patient in isolation, examining their symptoms and often deducing how unbalanced humors contributed to their issue. Hysteria was the umbrella term used for otherwise unexplained fits and externally obvious self-destructive behavior, with its victims so noticeably in need of aid that they couldn’t be ignored.

No less dangerous, but more easily ignored, was a condition called chlorois. Known also as green sickness for the greenish tinge that affected girls presented and as the disease of virgins for the demographic most affected, chlorosis was a quieter, equally feminized and unknowable affliction but has become less known in modern parlance than hysteria. A diagnosis of chlorosis was applied to mostly younger women whose behavior was just as troubling as hysteria but far less extroverted. Its victims were, over the centuries in which cases were studied, nearly all white teenage girls.

The first reference to chlorosis comes from the German physician Johannes Lange, who in 1554 published the first medical description of the syndrome in a letter to an acquaintance about his affected teenage daughter. Lange, like Jorden fifty years later, did not suggest a cure for the observed symptoms. The behavior of Lange’s long-distance patient, known merely as “Anna” in his correspondence, had become of concern to her father, not for the girl’s well-being but because her increased emaciation was becoming off-putting to marriage prospects. Lange described her syndrome as The Disease of Virgins; the term chlorosis was first applied to the malady in the 1619 writings of Jean Varandal. By 1769, the English translation green sickness was applied interchangeably with the Greek term.

Both Lange and Jorden referred to the work of the prolific ancient Greek medical writer Galen of Pergamon, whose understanding of the uterine basis of all female health issues provided retroactive confirmation of current societal biases. Both physicians benefited from working in an era in which the translations of ancient Roman medical texts became more widely available. The closely timed re-introduction of both hysteria and chlorosis were part of a wider acceptance of the work of both Galen and the writer he described as his “God,” Hippocrates.

The symptoms, which became generally accepted to suggest this diagnosis, included lack of appetite, fatigue, and moodiness, similar to those that today may be treated as side-effects of the hormonal changes during puberty and when girls begin menstruating. Of greatest concern to both parents and physicians was its suppression of menstrual bleeding. Fertility was an important factor in finding beneficial marriages for young women, like “Anna.” Though pale complexions and slim figures were symbolic of conventional beauty at the time, the ability of women to bear children was of paramount importance.

The girls’ maladies could go unnoticed at first due to a societal expectation for young women to behave in a similar manner to the disease: meek, submissive, quiet. Chlorosis was almost an exacerbation of expected feminine behavior, only becoming concerning when it made them unable to function in society due to starvation. Unlike their counterparts with hysteria, these young women languished until their condition became medically dangerous. Hysteria was noisy and externalized; chlorosis was quiet but no less deadly. These girls were not subjected to the same invasive treatments as hysterics because their symptoms were less violent, at least externally.

Though the symptoms were different, both hysteria and chlorosis were seen as being derived from a troubled uterus. As patriarchal cultures viewed the duty of a uterus as childbearing, the cure for both syndromes tended to be marriage, followed by pregnancy and childbirth. As noted by Gabriel Andral in 1829, the physical and moral emotions of matrimony should stimulate the nervous system such that a chlorotic condition would be cured. When this was not an option, for instance in the cases of nuns, physicians such as Trabuc believed that physical activity such as horseback riding may work to stimulate the menstrual cycle back into regularity. The core issue, doctors believed, was that the blood no longer leaving the body through menstruation was retained within the body. This excess blood was thought to take purchase elsewhere within the body, disrupting the patients’ organs similar to the way a wandering womb might. Sex, or hearty physical activity, were thought to provide the impetus for blood to begin circulating properly; as a happy byproduct, this “treatment” would ensure young women could begin to serve their societal role as wives and mothers.

The pervasive understanding of both anatomy and gender roles prescribed that women’s bodies were meant for childbearing; a woman unable or unwilling to do so was considered deviant. Medical diagnosis and treatment were connected with social constructs, leading to the suggestion that women with either hysteria or chlorosis might improve their health through sexual intercourse and pregnancy. Embedded in this theory is fear or revulsion around women’s sexuality and childbirth, which contributed to the psychology of these women’s conditions.

The pervasive understanding of both anatomy and gender roles prescribed that women’s bodies were meant for childbearing; a woman unable or unwilling to do so was considered deviant. Medical diagnosis and treatment were connected with social constructs, leading to the suggestion that women with either hysteria or chlorosis might improve their health through sexual intercourse and pregnancy.

Women who lived unmarried long enough to be seen as spinsters, like convicted witch Elizabeth Jackson, would be looked at with suspicion for dodging this responsibility as well as for the potential health issues inherent in an apparently celibate lifestyle. The increased occurrences of hysteria would only serve to prove this point that sustained childlessness could become a serious health concern. For the pubertal girls showing symptoms labeled as chlorosis, many of which are still evident in people today who live with disordered eating, anxiety, and/or depression, they were shifting from the relatively protected role of child and into the treacherous role of being a woman in their society.

Following a resurgence in the early 20th century, perhaps based on the increased frequency with which women entered the workforce, chlorosis diagnoses disappeared almost entirely in the 1920s. A number of factors contributed to this decline: increased understanding of gynecology, the wider availability of nutrient-rich foods, and an increase in the median age for a woman’s first marriage. Women who previously could have been assumed to have one of these older syndromes were now treated for iron deficiency, depression, hormonal imbalances and other conditions for which treatments were available.

Similarly, hysteria evolved from a medical term to an exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement after the 1960s. Chlorosis refers in current scientific literature to its botanical definition. Both syndromes were the result of a 4,000 year old hypothesis about the functionality of female reproductive organs combined with Renaissance societal constructs. Both flourished in the late 19th century as the Industrial Revolution and burgeoning women’s suffrage movements challenged gender roles in society, then faded from use.

The women diagnosed with these syndromes undoubtedly suffered both from a series of horrific symptoms as well as from invasive examinations and attempted treatments. In the 21st century, women’s pain is still often dismissed as psychological rather than physical, a modern take on the past dismissive treatment of all women’s health issues as examples of the alleged inherent instability and overly dramatic nature of women. Women’s pain is often not taken seriously by some medical professions, and this continued dismissal contributes to women avoiding reporting their pain, sometimes believing themselves that it was merely psychosomatic.

Mary Glover was subjected to torture and interrogation in a 1602 courtroom to prove her many physical symptoms were genuine. “Anna” became the subject of correspondence between two men concerned how her health issues may affect her marriage prospects. The pain of each was transformed from visceral to theoretical, and their experiences became case studies that would intrigue generations of physicians treating new generations of young women who faced their own painful and misunderstood medical conditions.

Further Reading

Dawson, Lesel. Lovesickness and Gender in Early Modern English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

King, Helen. The Disease of Virgins: Green Sickness, Chlorosis and the Problems of Puberty. London: Routledge, 2009.

Ann Foster is a historian and freelance writer whose work has been featured in Bitch magazine, Book Riot, and School Library Journal, among others.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.