By Victoria Forster and Elizabeth Wayne

In 1964, two months before the Civil Rights Act banning discrimination in public places was signed in the U.S., Jane C. Wright, a black woman physician scientist sat around a table at the Edgewater beach hotel in Chicago with six white men. In what was a decidedly unusual scenario in those times, they formed an organization with the sole aim to revolutionize the clinical care of people with cancer. This became the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO), one of the leading oncology societies in the world. ASCO now comprises 45,000 members from across the world and hosts an annual meeting with 40,000 attendees and 6,000 unique presentations of new cancer research.

Wright quite simply, participated in starting a revolution that has saved the lives of many people with cancer, but she is still relatively unknown outside the cancer field. While Rosalind Franklin and Marie Curie are celebrated as pioneers in 20th century medical science, Wright barely enters the public eye as a representative of historical women in science. Women like Franklin and Curie are portrayed so frequently that they may appear to be the only women making significant contributions to modern medical science. This focus on a small number of white women, however noble in intent, is not an accurate representation of women in the history of science, and it erases a far more diverse group of women who participated in shaping modern medical science — women like Wright.

Dr. Jane Wright had a keen interest in fashion and the arts throughout her life, having a personal shopper at Saks in her later years.

Born on November 19, 1919, Wright was raised and educated in New York City. Wright was a talented artist and had a passion for landscapes, and she even studied art at Smith College before switching to medicine at the encouragement of her father. She was sharp and loved engaging in lively conversations at her home or even the New York exchange stock market she frequented later in life. She had impeccable style and like her science it was always kept on the cutting edge. Not many scientists can boast of having a shopper at Saks — of course, Jane Wright was no ordinary scientist.

In only three years, Wright graduated from New York Medical College where she had received a full scholarship, becoming vice-president of her class along the way. Medicine, it seems, had become a family tradition: Her sister Barbara Wright became a doctor; her father Dr. Louis T. Wright was one of the first African-American graduates of Harvard Medical School; and her grandfathers Drs. Ceah Ketcham Wright and William Fletcher Penn were graduates of Bencake Medical College and Yale Medical College respectively.

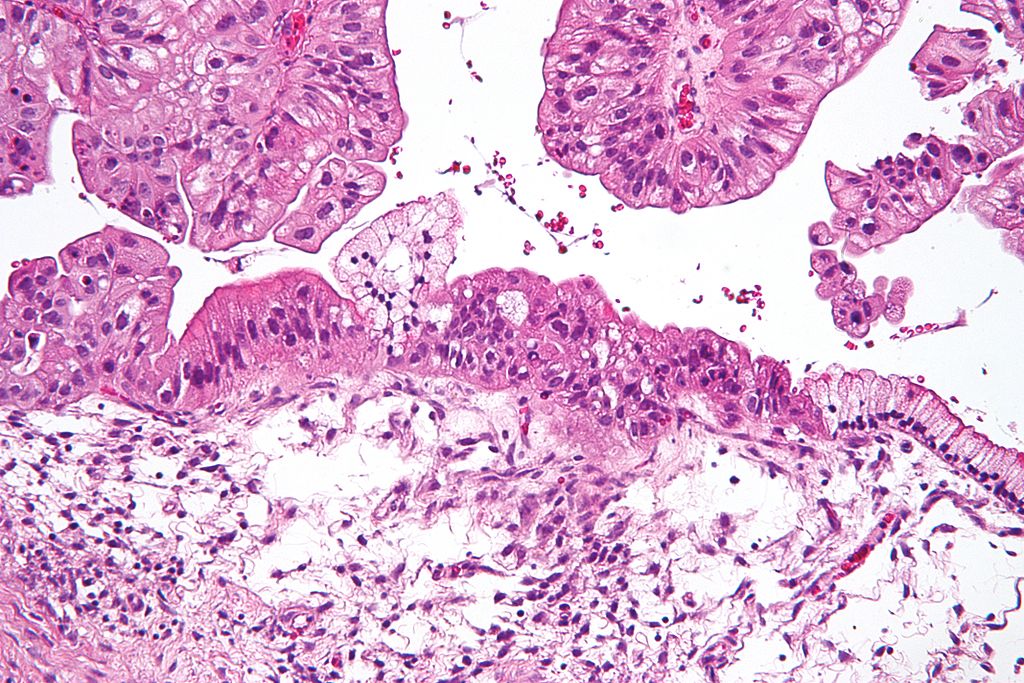

After graduation, Wright joined her father at the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem hospital. It was here that Wright began some of her earliest cancer research work. She focused on proving the efficacy of a drug called methotrexate in patients with cancer by not only testing the drug on people but also pioneering methods to test the drug on cancer biopsies from patients in the lab. These methods formed the basis for much of modern cancer research; methotrexate is still used as a chemotherapy drug in several tumor types, including breast cancer and childhood leukemia.

Wright’s accomplishments are celebrated among cancer research societies. There are several scholarships in her honor including the AACR-Minorities in Cancer Research-Jane Cooke Wright Lectureship and the ASCO and Conquer Cancer Foundation Jane C. Wright, MD, Young Investigator Award. However, Wright and other scientists like her were far from celebrated by the medical profession during the early development of chemotherapies.

Today, it would be incomprehensible for a cancer patient not to be offered chemotherapy, but Wright and her colleagues were working at a time when chemotherapy was a new and even taboo subject. The standard of care was surgical resection and possibly crude radiation therapy. Wright and her colleagues experimented with compounds derived from mustard gas, and the notion of giving patients who were dying from cancer a toxic chemical that resulted in soldiers dying on the battlefield seemed abhorrent to the medical community. The doctors who championed chemotherapy were seen as absurd, and some doctors, such as Min Chi Li, were even were asked to leave their roles if they continued chemotherapy treatments.

It wasn’t until the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon issued a “War on Cancer” that led to the National Cancer Act of 1971 and the founding of the National Cancer Institute, that the tide really started to turn. Oncology programs began to move from the fringes and into mainstream medicine with the medical residency programs finally offering medical oncology as a training specialty in the mid-1970s.

There are interesting similarities between the birth of chemotherapy and Wright’s own career. To study chemotherapy was brave and revolutionary for any scientist during the postwar period. It required vision, perseverance, and an ability to thrive beyond the conventions of what was normal. Similarly, Wright fought to conduct clinical research at the highest levels when women and black people were just gaining admission to many US universities. That Wright pioneered chemotherapy, normalized its acceptance amongst the medical community and then co-founded the whole field of medical oncology is fitting. This is the type of leadership work that women and particularly women of color have done both inside and outside of the sciences.

Despite being a renowned scientist and responsible for the implementation of one of the most successful chemotherapy drugs to date, Wright was often asked was whether she believed race and gender impacted her work. In a 1967 interview with the New York Post, cited in a New York Times obituary, she said that she was aware that she as a black woman was a minority representative of two groups in an institution that was overwhelmingly white and male, but she added, “I don’t think of myself that way. Sure, a woman has to try twice as hard. But — racial prejudice? I’ve met very little of it.”

Dr. Alison Jones, one of Wright’s daughters, said, “She never discussed race being an obstacle to her success. She looked at obstacles as challenges to be overcome and never backed down because something was difficult.” Wright, of course, did not operate in a world absent of institutional racism and sexism; she did, however, refuse to be limited by it. She both broke the conventions of what a scientist looks like and created the mold for how our generation of doctors and scientists tackle cancer today.

Dr. Jane Wright in her medical office in New York City.

Science has historically been constructed as a white male discipline, and it remains hostile to women, particularly women of color, despite increasing numbers of women choosing the profession. Wright’s career has many of the same qualities that help us remember well-known men of science, like the ingenuity of Stephen Hawking or the innovation of Nikola Tesla, but she is not awarded the same recognition.

Wright was on the cutting edge of cancer research, but the public has been content to forget about her, contradicting the popular refrain that if women scientists really are equal to men that their accomplishments would speak for themselves and we would recognize them. Her ambition, character, and intellect should not be erased because of how we think a scientist should look. She wasn’t trying to fit into anyone else's shoes or structure of how she should be a scientist; she cultivated her own space and identity. Her story should not be eclipsed by a handful of stories about famous white male and female scientists. Within the oncology community, Wright is remembered as a “visionary,” and it’s past time for the public to recognize her as one, too.

*Editor’s Note: The authors will be donating their fee to Vanguard STEM, an organization supporting women of color in science. To learn more about Vanguard STEM or make a donation visit their website here.

Victoria Forster is a cancer geneticist and writer with bylines in The Guardian, The Times, and The Conversation.

Elizabeth Wayne is a TED Fellow and cancer immunotherapy scientist.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.