[This is a modified, expanded version of the text of a performance/treatise/non-film that a proxy version of myself gave at the Whitney a while back, from behind a black curtain.

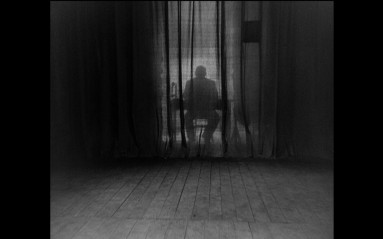

It is, in one sense, a theory film by other means, spoken by famed hypnotist and criminal mastermind Dr. Mabuse, now worse for the wear having been generally discarded by the 20th century. The rest explains itself. In the actual event, the text was read by my voice. It was an audio piece, for a specific physical space. However, given that its concern is that of the relationship between opacity and communication, with the act of trying to elaborate together - conspiring - as the mechanism between them, the kind of non-film it is means that it is makes more sense if routed through the particular voice of any reader, not mine in particular. For proper effect, then, read aloud, as if somewhat hypnotized by a long-dead German. Preferably do so in the company of confused pets and loved ones.

The starting video is one part of the accompanying video made for this. It should be left on loop, at medium volume, or put on another screen, so that the voice receives the proper accompaniment of British schoolgirl agents of total social negativity.

The other important note is that the performance happened on May 6, a few days after May Day.]

Let me tell you about a conspiracy.

In the past, I wouldn’t have needed to tell you about a conspiracy: I would just tell you something, I would say “section 3B, dynamite the radio tower” or “replace the currency in the bank with fake currency to admix the reserve and hasten the dissolution of global stability” and you would do it. You would conspire without the choice to be in on the game or not. But one doesn’t speak about a conspiracy while it is happening, only when it has ceased to be the current that gives obscure shape to the failure of what is.

It was a long century, and I was all over it. My grand project - the Empire of Crime - was the stuff of legend. To try and laugh it off, they made 12 films about me. The laughter didn’t stick, or rather, it caught in the throat like a bird, so they tried other things. Lang made me hopelessly insane by the end of the first film, then let me die in my pajamas midway through the second. Shameful. Although most of that film is rather embellished, that part was true. I died 89 years ago. But although my name caused fear of the soiled trouser variety, I never was much of a man. When I was, I was just a million crimes. Ten thousand disguises. A thousand eyes. And a floating voice. Even before I died, I wasn’t content to keep my voice tacked to my charnal frame or to wait to be knocked off in my filthy linens. And so one night, without even a drop of brandy to fortify me, I took the knife from my desk, and I did what had to be done. A knife is sometimes a metaphor. But the tongue never is.

That was in 1933. We all know what happened after that. That was the first time they stopped thinking about me in the 20th century, because I seemed too inseparable from what happened. But I was a criminal, not a state, a dead man, not a live people, a nihilist, not a fascist. All the same, I know I have blood on my voice.

But then the years after like springtime for capital. Lang dragged me back in ‘60. And then the rest followed, safely scrubbed of any Weimar grit, spiffed up in a new garb of genre glee. 7 films in 10 years bore my name. A celluloid sprint of blind men, death rays, and a whole lot of pulp. They redubbed Scream and Scream Again in Germany to make it more Mabusey, although that all ended in an acid bath froth. By the time Jess Franco got to me, there was nothing left but a name.

That was in 1970. We all know what happened after that.

In the years I’ve had to think since, I noticed a strange correlation: my disappearances from the cinema correspond with global economic crises, with stagnancy and depression. It is, I suppose, easier to think of masterminds during boom years, of a controlling voice on whose words blame could be laid for superficial ills. After all, when things truly go to shit, there’s no conspiracy, no speech: there’s just what is, laid out as open as the desert.

I should note that they still haven’t needed me since then, which, depending on your politics, bodes ill or well for all of you here before the screen.

No, they haven’t made a film about my voice for 23 years, not since Chabrol’s failed try in ‘89, and even then, they couldn’t quite bring themselves to say Mabuse any more, even to say the name alone as Franco had done. They had some jackass pretending to be me, and they called him Marsfeldt. My god, Marsfeldt.

Perhaps they will make a videogame. I do like the ring of Doctor Mabuse: Ghost Recon. But the phone is quiet.

There’s a story I read called Lucifer Unemployed, by Alexsandr Wat. It tells of how Lucifer returns to Poland, to wreak hell on earth, as usual. He finds, to his dismay, that there’s no more work for him: the present has got it covered, thank you very much. So he goes to Hollywood and becomes Charlie Chaplin. My story is similar to that, except for the fact that I controlled Chaplin for most of the ‘20s, until he started speaking on film, at which point, the spell was broken. But like Lucifer, history beat me at my own game.

So I holed up. I watched a lot of films. A non-man with a thousand eyes can cover a lot of ground. And because they weren’t going to make another film about me, I decided to make this one: it’s titled Doctor Mabuse Dispassionately Recites Communist Theory Over Found Footage of Riots. Or The Ekphrasis of Doctor Mabuse. Or just DM13: The Final Gamble. It’s not much of a film, I know. But I read somewhere that as long as one movie camera exists in the world, all one has to do is declare that whatever one does is a film. So I’ve borrowed this hypnotized body, this American voice, this little screen, for a while. One can’t be picky. So be it. We play the throat we’re dealt.

I decided to make a film because I noticed something about films that confused me. For nearly a century, I’ve only been a voice. A calm, deadly rational voice. A voice that sees all and describes and says what is to be done. A voice that gets under the skin, in the pores, up in the tongue. A voice without a body, other than the body to which this voice is nailed for the moment.

What confused me was why so many of the films I saw seemed to feature a voice like mine. Especially in those films, from across the globe but particularly the West, from across decades til now, that see themselves as directed against the dominant currents of the cinema and the world, films that are projects of making sense. Why, I asked, in so many of them, was there a floating voice that spoke out over images of crime and confusion and banality, over a landscape of the busted present? Why was the voice that spoke one which had no body on screen, or when it did, why did the voice not match the lips? And why, when they spoke about urgent matters, matters like the ruining of the bourgeois subject or the massacre of the Palestinians or, above all, about the attempt itself to say things of importance, did they sound so cold, so hushed, so monotone, so dispassionate, so bored?

For a moment, I thought I had the answer. Perhaps I had gotten blackout drunk and gone on a epic, 15 year bender, during which time I orchestrated the production of a rash of important French radical documentaries and art films. But I checked my files and confirmed that, indeed, I have never hypnotized Duras, Resnais, Bresson, Straub, Debord, Marker, Isou, or Lemaître, and most certainly not Godard, even if the intonation of most of the voices in these films sounded already hypnotized.

(Nor, for the record, did I go on a boozy spree and hypnotize Hollywood into installing bodiless voice-over narration in a good half of film noir. I neither recorded the beginning of Hitchcock’s Rebecca nor established the basic sonic structure of mainstream documentary filmmaking. And I most certainly am not responsible for Bob Saget droning like a ham-tongued bee over the flashbacks of How I Met Your Mother.)

No, I didn’t do any of this. The voice has been off the chain from the start.

There is a film called Treatise on Slime and Eternity. A man strolls around Paris, as one does in films of this nature, while disembodied voices argue about whether or not sound and image must be connected. A man’s voice declares, “The connection between the images (perhaps coherent in themselves) must be severed.” To speak about severing the connection between the images, about generating incoherence, doesn’t mean amongst those images. After all, how have two discontinuous spaces ever been coherent? There’s a reason they call them cuts. No, the incoherence of images - the basis of a Discrepant Cinema - will be in relation to the sound.

The urge for the severing seems on point: indeed, in most film, sound is chained to the image, the voice tacked to the body. But we are not speaking of any sound. We are speaking of the voice that says words. And there the case is different. For think of the intertitle, that written voice, think of the majority of films in which all that exists, every cut, every reframing, is to show two heads talking to one another, of how a tidal wave will be raised just so that Tea Leone can finally tell her father that she loves him, of how murders will spread so that the name of the killer can be spoken. This is the question, then: in what way is a voice talking over images of something other than a talking body in any way a break with what cinema has been?

Because that hasn’t always been the case, by a long shot. Think of the sound artists in the cinema of attractions who, when there were horses in the film, would make horse sounds but not matched to action, just whinnies and clomps forming a loose atmosphere of horseiness. Think of what the French called the conférencier, or the bonimenteur, that so-called “vile accomplice” of the exhibitor: they presented silent films, just like magic lanterns, speaking over, about, around the images, cracking jokes, bantering, telling the story. In Korea, they were called byeonsa (??). They were famous. People would say they were going to see a byeonsa, rather than going to see a film. In Japan, they were called benshi (??) They remained in the cinema until the ‘30s, until filmed sound shoved them off the stage. Kurosawa’s brother worked as one. When talkies took away his job, he killed himself.

Think of the intertitle. It started in 1903. Sometimes they gave information - Trouble at the precinct or just the word POVERTY -, often they wrote the words that might have been in the mouths that moved before and after. There, the voice was already separate, as though there was ever a pure silent cinema, from which the voice could be expunged and fenced into a separate pen.

Sound did not arrive like a thunderclap. It was already there, in the silent film. As Bresson put it, "the characters did in fact talk, only they spoke in a vacuum, no one could hear what they were saying.” The voice was present, it just had no volume. It’s why it is better called it a deaf cinema, not a mute cinema. And there were the other sounds: the settling of chairs, whispers, laughter, the sound of the projector, music. All peripheral, yet part of watching the film. When film began to project its own sound, it was piecemeal. Sound sequences shoved into recently shot silent films to retrofit them for market. These were called “goat gland films,” named after the quack procedure of giving men goat testicular glands for pep and vigor. (Needless to say, it was less than successful, on men and films alike.) But when sound fully arrives, when the sound of a voice is played at the same time as a mouth opens and closes, that sound went from buried in deaf silence or written out to floating, undone. Because envision as we might, the voice doesn’t come from the grey space between those lips looming high. It comes from the same speakers as the sound of the grass, the tolling of the bell, the pistol, the trumpets. Spatially, there’s no difference between the voice that has something to say and the tree that creaks in the wind. Mentally, we perform what theorists of this call a triage: the act of separating out, of trying to echo-locate what has no distinct source. But like the other sense of triage, one begins with wounds, with things already severed, missing, all out of whack.

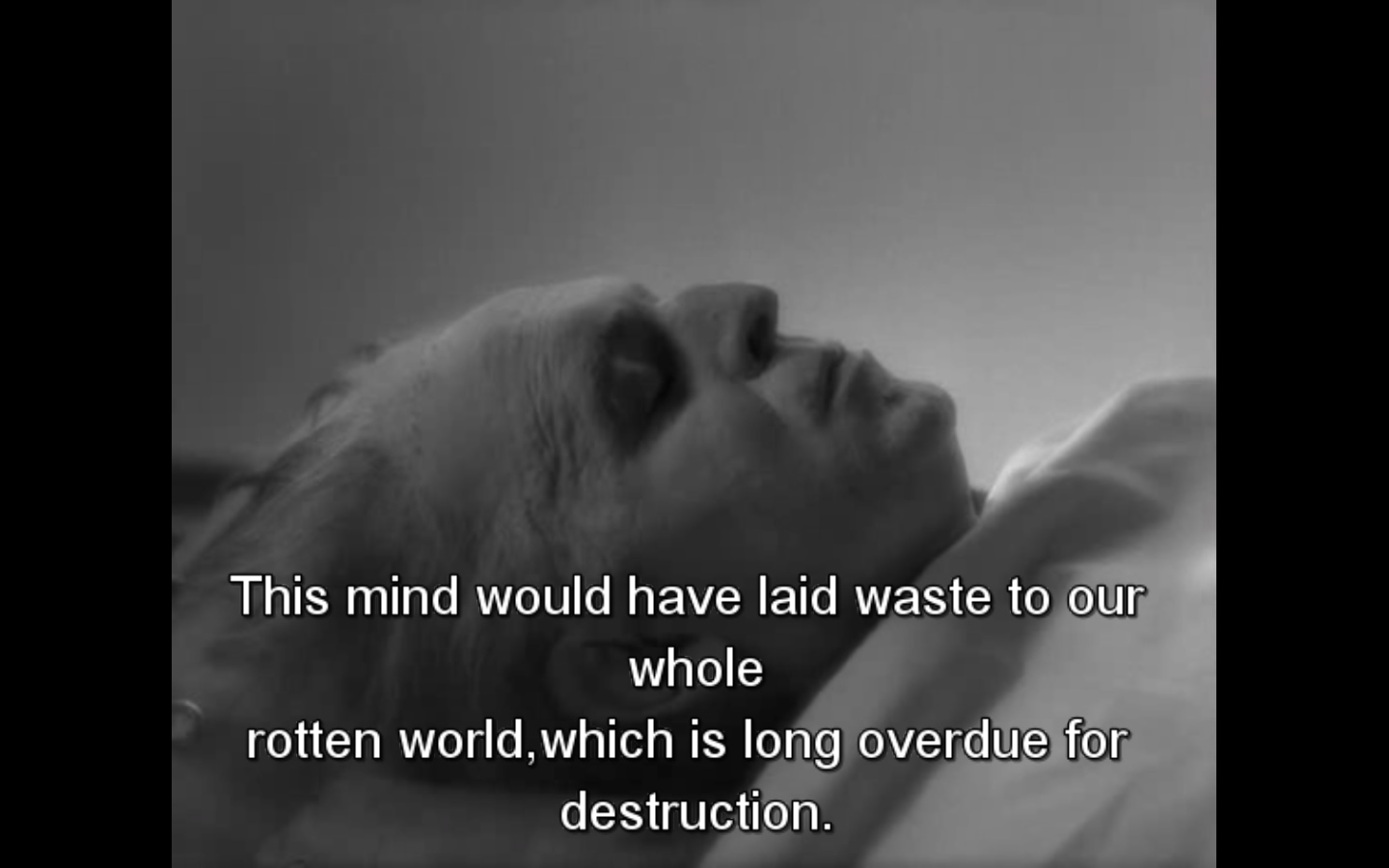

This is true of the famous scene in the second film about me. The intrepid young lovers are trapped in a room and face a curtain, behind which I, Doctor Mabuse, sit at my desk. My voice booms from behind it. I have condemned them to die because the man has betrayed me. He does not like this and fires his gun through the curtain at me. Silence. They walk to the curtain, throw it back, and... BOOM! No Mabuse! Just a wooden silhouette, a small speaker.

This scene passes through three moments of vocal horror. First, the voice is unnailed from its expected source and revealed to be acousmatic: there is a voice, yet the body to which it belongs is nowhere to be seen. Second, worse, the voice is nailed to the wrong things: an empty desk behind a curtain, or a body hypnotically borrowed. And indeed, it’s a nasty shock. No one wants to be instructed by a piece of cardboard to enact the chaos of the modern. But third, and worst of all, is that when you watch it, regardless of whether you, dear spectators, face your heroes or face the curtain, the fact is that my voice came from the same place, every time… from the screen itself. The voice, once untethered, once undone from the benshi and intertitle, gets everywhere, on and off screen. It is simply in the room, in the cinema. And yet it is not reducible to that space. The particular destruction of the amps that project it do not alter the voice, which speaks elsewhere, which spoke long ago and makes its proclamations to those who mistake it for a living source, for what could be shot.

These are the preconditions that underpin those films I watched, those films called radical, the récit and ciné-essay, all those films that take on the contradictions of film form and history as their form and material. First, there are the conditions of the cinema of attractions and of the byeonsa, which the cinema industry has gradually denied. They will be picked up once more by communists and pulp directors alike. They will set the sound loose again, they will let it be obscured by whatever else happens to be present when recording direct sound, even if it drones out the words. They will use intertitles. Above all, they will narrate, describe, comment, riff, intone, recite.

Second, there are the conditions that obtain in unbinding the voice from the body, the three-fold process spelled out in behind-the-Pythagoran-curtain scene described before. It is, god forbid, what one might call dialectical. If this were a different kind of film, I would read a passage from Marx’s Grundrisse and not explain it. Or a French woman would read it. And not explain it. But this is not that kind of film. And so. To be clear: the scene from Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Doctor Mabuse unfolds the conditions of the voice that will mark much of radical film.

First, the voice is undone from any particular subject visible in the frame: it declares itself already beyond the purview of expected codes of conversation, narrative development, and psychological depth. The voice will speak of, or alongside, what images occur, but not within them. It comes from elsewhere.

Second, it is, however, a particular voice. From a specific body, one not seen, but one that bears traces of specificity: a gender, an accent, a race, a nationality, an age, a rhetoric, a lexicon, an affect. Of a technology: a quality of microphone, a tape recorder. The voice is tied therefore back to a speaking source.

Yet - and this is the third, the turn of the screw - the voice emerges from the same apparatus that plays all other sounds, including those which correspond to present images. This apparatus is the film in total. The voice, therefore, is the voice of the film itself, however at an internal remove. It emerges as undifferentiated from the materials from which it distances itself. And it is indifferent to what happens in the space before the screen. It cannot change its tune.

It is this final contradiction - the voice distanced from the material it cannot be separate from, or the bound separation - which is the voice’s crux in these films of critique. It gives rise to four further aspects of them.

First, it will often be a voice which sets itself apart from the film: it comments on the nature of film itself, it comments on its own commenting, it acts as if it has already seen the whole film. It is concerned with the film and yet not reducible to it.

Second, in so doing, it posits itself alongside the viewer, as if to say: like you, I too am watching these images, and I am speaking about it. This is something about which one could speak, about which it is important to speak, and to speak in the space that is not reducible to the canned dialogue of characters. And yet here lies the problem. The voice still comes from that undifferentiated screen. It can play at dialogue, but it cannot respond. That’s the cutting edge of Lamaître’s Ever the Avant-Garde of the Avant-Garde till Heaven and After, which calls itself a “supertemporal” work, one which invites the reactions of the audience, claims to incorporate them, yet which acknowledges that this is, ultimately, a rather paltry participation. Because barring the destruction of the print, when screened again it will make the exact same offer, untouched by whatever those prior reactions may have been.

Third, the voice is not a voice of narration. A narration is constructed as proper to the film: no matter how off-screen, it assumes that the on-screen won’t function without it. These voices instead are those of ekphrasis. That is, of the description of a work, or materials, in a different medium. In this case, not a painting of a poem or a poem of a film, but of the bound separation, the internal distance: from the film that has been made to the film that has been watched. Often, this transposition between registers takes the literalized form of trying to turn the voice into one not of film at all but of politics, of philosophy, or, worst of all, art theory. It reads passages from the Grundrisse, it tells you that it is a commentary of the status of film and politics, philosophy, or art theory. But this passage from the ekphrastic voice as the deixis of critique - that which points out its separation - to the voice as the recitation of criticism is incidental and need not be the case.

What matters is that this mode of speaking is the inversion of the voice that comes through the police megaphone, a voice which declares itself a proper expression of the polis. It booms out over a set of materials and describes them. It describes them as not worth seeing. It says: Move along, there is nothing to see here. The ekphrastic narration says the inverse. It declares itself unmoored, in and out of the film. It speaks over the gathered materials and describes them as worth seeing, even when it does so by pointing out the irrelevance of the images.

It says: Freeze, there’s something to see here.

The last common condition, the fourth, emerges from the attempt to produce the sound of that ekphrastic voice, one carefully emptied of all affect and particular expression, the flat, slack, hushed, and cool voice, the narrating voice, the dispassionate commentator, even as it invites a riot or speaks over the images of one. It acknowledges the effects of what it shows and says, but it speaks as if untouched by them. In so doing, it walks a fraught line: by producing the semblance of abstraction in the service of trying to spur a process of critique, it draws a suspect division between affect and abstraction, as if getting a correct grasp on history meant disavowing the subjective conditions it generates, as if it meant settling down and speaking softly into the mic. The rabble takes their seats and one by one, learns to sound as if they don’t really give a fuck.

Let me tell you about four films that speak differently.

There is a film called They Do Not Exist, by Mustafa Abu Ali. It is about Palestinian resistance. There are bodies on screen who speak about what they do. Then a voice that is not bound to a mouth on the screen speaks, a child who is urging the fighters to continue. The fighters are reading letters on screen at the time. As if it is the letter of that child. This technique is common from so many films, particular ones about individual loves or dramas. When the voice says, Dear John, If you really love me, then you will not try to find me. Try to understand. Our love is impossible. Our families will never leave our love in peace… But that voice is not impossible. It is the voice of the loved and the point of it is to ensure that those particular luscious lips and longing eyes will be dragged onto screen once more to collide with a man who has a bit of stubble of a jaw like a fjord. No, here the voice speaks from a different position of impossibility: from those who have been declared to not exist and yet who do.

A film called Definitely Sanctus is definitely about heimat, that noxious congelation of the old and the new, which gloms together in such a way as to evacuate them both. The film does not talk. It does the only thing one can do in the face of that sticky mess of Bavaria and health and void. It yodels. You can’t reason with heimat. But you can yodel over it.

There is a film called Traktora, made the Aleinikovs, 2 years before the USSR stopped being the USSR. In it, a voice speaks over propaganda materials regarding tractors. It may seem hard to be excited about tractors, but, historically, it has been hard not to be. There are several voices. They do not stay calm, they do not stay on track. Time slows to a crawl, like a tractor in a bog. The voice is drawn out as codeine. It is the sound of the double-effaced coin that oscillates between plan and market and reminds us that neither has ever made life adequate for the living or for the dead, although the scores of the dead tally immeasurably higher for the market. The sound of this double failure cannot be pronounced dispassionately. It is insupportable. So in Traktora, a man’s voice starts to speak normally, as if he was speaking about tractors, because he is. But because the voice can only be about the way that history collapses in on itself like a burning cathedral’s leaden roof, time sags under its own weight. The voice drawls. That is one sound of history. It is one way to speak when what one has to say matters, when that saying drags with it the impossible weight and matter of a century. That is not the only sound of history. There is also a woman’s voice. It becomes impassioned, restless, hysterical, not because she is a woman, but because to speak dispassionately about what was supposed to be objectively the case is to resign oneself to its inertia. Between these two voices, whose bodies are nowhere to be found, the images bear sense.

There is an Iranian film called The House is Black by Forough Farrokhzad, about the ugliness of the world. It declares itself about this, in the darkness, before it shows anything else. A black screen is an image. But it is not ugly, even though all that has been black has been called ugly and evil for centuries. A man’s voice says this:

There’s no shortage of ugliness in the world. If man closed his eyes to it, there would be even more. But man is a problem solver. On this screen will appear an image of ugliness…

[It says this because it does not think that blackness is an image of ugliness. This is important. This is why it says will appear while the screen is black.]

It continues: a vision of pain no caring human being should ignore. To wipe out this ugliness and relieve its victims is the motive of this film and the hope of its makers.

Then it shows an image which is different from the black screen. It shows a face, partially veiled, looking at itself in the mirror. The camera zooms in. The eyes are lidded into near closure. The nose as if melted. The painted flowers on the mirror obscure that self-obscured eye. It is the face of a leper. There will be many such faces. The film is about a leper colony.

If one listens to the voice at the beginning, one might think that the image of ugliness is means the ugliness of the faces of the victims shown as images, the faces torn from inside by the slow claws of bacteria. But it is not. The image of ugliness is not this. It is all that cannot be shown: the political, economic, and social network that perpetuates the ugliness of the face, that cannot bring itself to care because it is a system of relations, not a subject, and because the ugliness of the face, of leprosy, is sequestered. It is made separate. It is the proper physiognomy of separation and all that enforces: not the jowls and strong jaws of men who rule, not the blurry screen of the cop’s mask, but the living death’s head, decay in process, put where it is not to be seen. The image of ugliness desequesters. It brings what cannot ever be an allegory into matter, by means of making it seen.

But still, this is not the image of ugliness. That is an image that, in this film, cannot be shown. Instead, it has to be spoken. And it is spoken, by bodies not on screen, spoken by describing the medical specificity of the disease and by reciting lines of poetry. The two alternate. They are not a chorus but a dialogue, a separation that is necessary to get heard the other separation that is hard to see or say. At one point, the woman’s voice says, “Who is in this hell praising you, o lord? Who is in this hell?” The answer is the same to both questions. Those with leprosy are praising. The third and fourth shots of the film are children reading a thanks to God from the Koran. And they are in this hell. And we are praising, and for this reason, we are in this hell. And that we is not a metaphor, even if there are only some of us whose faces are thick with lesions while we still breathe.

In my day, I was known as a great conspirator. As a criminal, I was flattered, touched even. But it was never true. I was a great talker. I talked people into things they never should have done. I had a silver tongue. But silver is not a conspiracy, even if it lies underground. To conspire means to breathe together. The great conspirators of history spoke in hushed voices. They met in places that were called underground and even there, they put their heads closer together, as if to kiss. They spoke close enough to breathe the same air. To conspire well you have to be in the same space. You have to share breath like a kiss, because only then do you realize that the same pollution that fills the lungs of one fills the lungs of all. Who breathes the air of hell? Who can remember the taste of anything different?

A film cannot conspire. Like me, it can only ever talk at you. It can claim to lay bare the mechanism by which it speaks - as I do so by means of talking behind this screen, which serves to idiotically literalize the condition of all film - and it can therefore assume that this has become a conversation. But that would be what is fondly known as total bullshit.

But the space into which a film speaks, or weeps, or screams, or giggles is a space that belongs to conspiracy. And not only because it tends to happen in a room that is dark, which is a space in which those who might aim to conspire can congregate, not because the dark is criminal, but because it is easier to share the same breath. The cinema is a space for conspiracy because it used to mean a space to gather. To be not in the home, not on the job. We used to come together in the cinema, and not only when we were watching sexy shit.

There has long been an investment in the idea that we used to not understand the difference between a screen and a room. It’s very important to us to be able to claim that when the train charged the screen, we shat our pants and only decades later learned to realize that while there is a vampire in the room, he will not put those choppers in our soft necks, no matter how kindly we ask.

As for why the same claim is made about the workers exiting the factory, I do not know. What a thought! A roomful of spectators recoiling in horror as the workers flood the gates and march or amble toward us all… Because a storm of workers leaving work behind is far more frightening than a train made by workers. As Platonov reminded, railroads must be treated with care, because they cannot heal themselves. Workers can, and when they stop working, they can also lay waste to all that has insisted that they remain forever workers.

But people used to run riot in the theaters. In the years of the Great Depression in the U.S., cinemas had to stop showing newsreels that were too optimistic about the state of economic affairs, because people roared, with laughter and rage. We used to throw popcorn and fits. This has been lost.

In front of the idiocy of that voice which spoke over images of grain and roads and labor, they added their own voices, a tremendous conspiring voice of mockery. And there are some who would say that this is just chaff in the mill of spectacle, that cinema is a fire-break of dissent, a steam-valve and when those watchers let vent in front of some flickering images that could not respond to them no matter what they said or did, immutable even as the speakers were torn down and the projector set aflame with its nitrate kindling, that when these spectators did that it was merely a dissipation, an irrationality, a distraction. Those who say this are fools.

There is no such thing as political cinema. There are only political occasions in the cinema. Sometimes those are sparked by films that speak calmly, without affect, which read extracts of theory over images of riots, over police, over bodies starved and beat, over the relations of power embedded in the kitchen, the highway, the bedroom, the city, the desert. Sometimes those are sparked by films that speak, in whatever tone, of recovery, of a “post-racial society,” of the trials and tribulations of two tan and healthy persons to overcome their differences and start a family. Sometimes those are sparked by any voice, by any image whatsoever. But film can never speak what happens in the room before it. To that, it remains blind.

And the fantasy has never been to pull down the screen in order to see what lies behind it. Because nothing does and never has. Because the film, like me, does not know what you do or who you are. Like it, I’m clueless. I recorded this in another country. For all I know, this room is empty, save for a drowsy fly or two. I don’t know if my surrogate has gotten bored and wandered off. I do not know if you have torn down this screen and found the obvious, that I am not here. I recorded this the day before the first of May. I do not know if this is even to be played because the chance remains, however small, that things went down, that business did not return to usual immediately after that day, that it became a week, a month, that the city choked on itself and those with courage made of that stuckness something to endure. My sincere hope is that the occasion for this to be played has been cancelled, because of what this would mean.

I am not speaking from behind a curtain but from somewhere underground, in the dark, with my own breath and its pollution, in a cinema for one. Those who rule above have no need for such dark. They simply talk and they command, and they claim to see all, through drones, around firewalls, into bunkers. But it’s not the task of film to cast light. Cinema is not a late enlightenment project. It is not a conspiracy, but it is one form of thickening the curtain, of restitching it where it has been torn by power itself, of providing the occasion for a gathering and a split. It darkens, it gives matter. A critique of separation doesn’t mean the abolition of separation. It means the making irrevocably evident of separation. Like spray paint on a surveillance camera lens. Because opacity is a no-way street. Only then can one actually start to determine where there is a real distance and where there is a terrible proximity, made all the worse for being so divided against itself.

Opacity divides those who just talk and those who conspire. A film is such opacity, already, but it is through speaking, first in letting the voice come undone and then in drowning out that voice by those who sound less bored, that the image of ugliness and incoherence comes closer to sight. With it, a small contribution to the slow process of becoming uncivil, in dark and light both.

This, then, is a film dedicated to those who conspire.