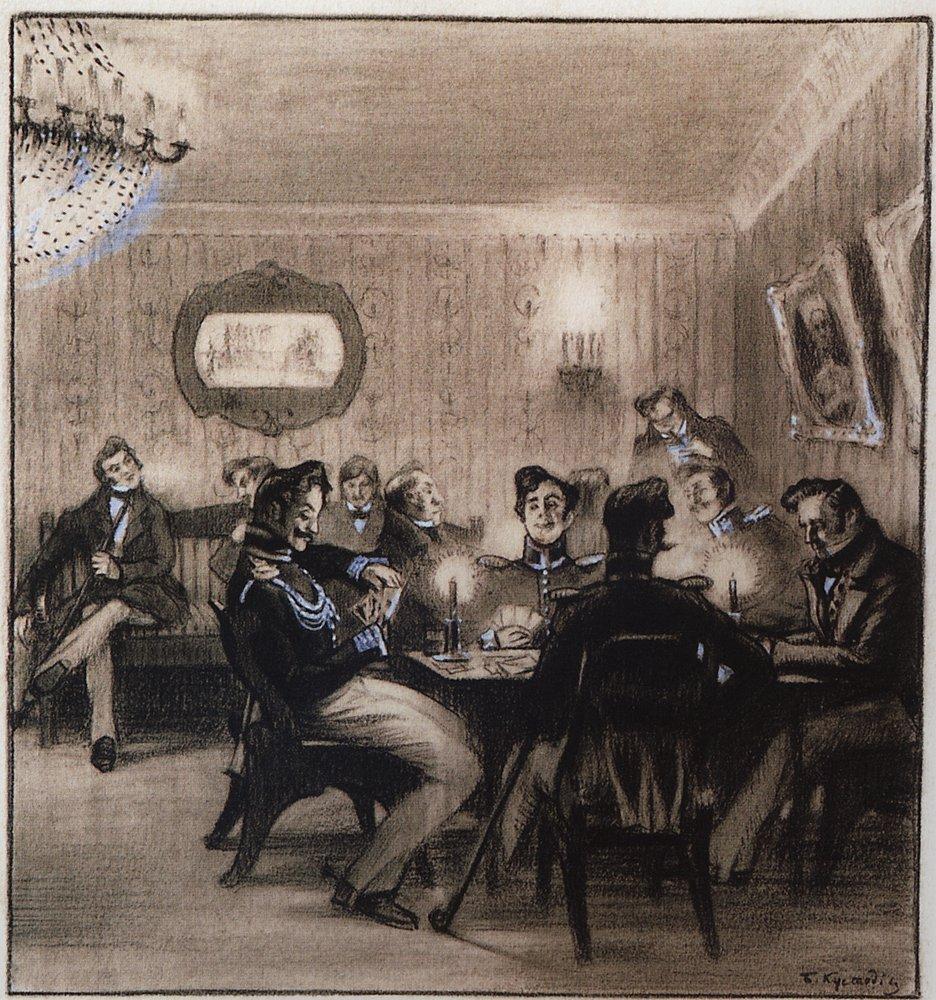

Sitting at a card table and playing bridge with friends is probably my personal-scale utopia. The scope of society is condensed to four people, a comfortable number when you mean to pay attention to all of them. The activity is highly structured, down to whose role it is to shuffle and whose role is to deal any given hand, but interwoven with conversational spaces that aren’t open-ended, making them not so arduous to fill. Everyone settles in. An easy rhythm of exchange settles in amid moments of deep concentration; the arcane system of bidding and carding signals between partners is complemented by a relaxed flow of asides and anecdotes, and everyone’s competitive impulses are restricted to the game. They don’t play out in obscure ways in the social interactions themselves.

It’s probably hyperbolic to call games like bridge a “social technology,” but they do make a certain kind of sociality possible for introverted people like me, establishing a sense of connection that is sustained by the game’s rituals and more or less arbitrary stakes. So it never fails to depress me when the principles of games that structure social gatherings are co-opted by what we more conventionally think of as technology, which decontextualizes and deploys these principles for antisocial and/or commercial ends. Let's turn humans' proclivity for structured intimacy and turn it into an isolating trap!

Gamification is awful for many reasons, not least in the way it seeks to transform us into atomized laboratory rats, reduce us to the sum total of our incentivized behaviors. But it also increases the pressure to make all game playing occur within spaces subject to capture; it seeks to supply the incentives to make games not about relaxation and escape and social connection but about data generation. The networked mediation of games -- in other words, playing them on your phone or through Facebook -- undermines the function of games in organizing face-to-face social time, guaranteeing presence in an unobtrusive way. Instead we typically take our turn in mediated games on our time and play multiple games at once, to cater to our convenience and our desire to be winning at least one of them.

During my brief experiment with Words with Friends, I ended up with a bunch of games going simultaneously, and little investment in any of them. I felt like I was playing a row of slot machines. I don’t know who my opponents even were. One of them, I'm pretty sure, was using a program of some sort that generated the longest words out of their given tiles. They may have well been machines. They may as well have regarded me as a machine. Mediated game playing dehumanizes the opponent and ultimately dehumanizes you. You may as well pit computer against computer and watch the outcome as a spectator, wait for them to learn that games basically aren’t worth playing, a la War Games.

But tech-industry ideologues continue to insist on gamification and mediated games as if they are natural outgrowth of consumer demand rather than a demand the technologies have instigated, and they argue for a continuity between behavior that seems to me antithetical. Playing bridge online is pretty much the opposite of playing at a table with friends -- there is no sense of connection, no aura of communal presence, just the mechanics of the game executed through a cold digital portal. Social games are a lot like social dances; one wouldn't try to square dance on Facebook, neither should one try to play bridge that way.

But still, the existence of mediated gaming makes it that much harder for individuals to agree to sit together at a bridge table. It’s hard enough to get people to sit at dinner without disappearing into their phones. And if you are busy playing pseudo games on your own time, why bother agreeing to the compromises to make yourself present to others? What badge is in it for you? Though actually someone probably has already gamified the desire to play games in person, and I can check in to Foursquare and become mayor of the bridge club.

Worse than the co-opted games are the Zynga-style games that are symbiotic with Facebook. These don’t prompt sustained interaction with friends in one’s network so much as they prompt sustained interaction with Facebook, generating data that the companies can either sell to marketers or use themselves to better program your interaction.

As John Ferrara, author of Playful Design, explains in this disturbing interview with O’Reilly,

Games can produce enormous volumes of data because it's really simple to gather every little interaction the player has in the game and report it all back to a central server. This has immediate applications for game design itself. Zynga, for example, uses data to determine which design choices create greater tendencies for players to stay engaged longer, involve more friends, or pay to enhance the game experience….

I would suggest that financial services could be one of the biggest secondary beneficiaries of such data because there's so much to learn about how people make financial decisions under different circumstances.

Sounds pretty great right? The way you play a lonely game online designed mainly to get you to provide data will eventually allow banks to better game you to maximize the fees you end up paying to have an account.

This seems typical. Games mediated by commercial entities lose their integrity and are instead implemented to reshape the incentives of players to conform with the game providers' needs. They redefine what we are supposed to experience as fun, catering and reinforcing the impulses that suit capitalistic ends. In capitalist society, after all, isn't making money the only game really worth playing?