Enlightened government, humane ethics, and bustling trade meant that even the lowliest in the Low Countries shared in the high times

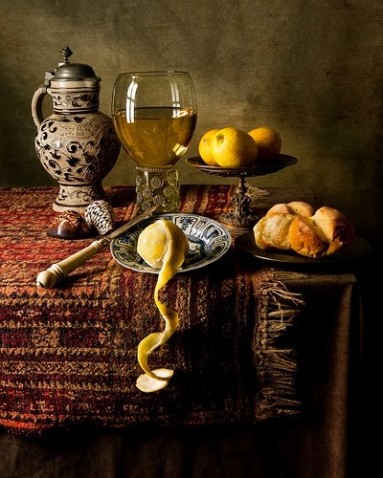

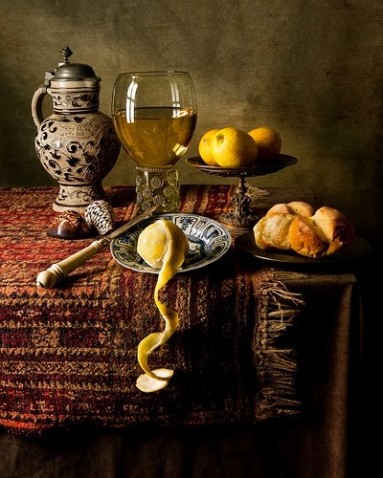

Willem Claeszoon Heda, Still Life with Crab (ca. 1650)

"Much wisdom is smothered in a poor man's head." --Dutch proverb

The 1806 summer trip British writer and barrister John Carr took through Holland wasn't easy. The Netherlands and Britain had long been enemies, and he had to borrow a passport from an American friend to sneak past customs. The subterfuge paid off.

Lord Byron met Carr at Cadiz and was so impressed by the man that he referred to him in Childe Harold as "Green Erin's knight and Europe's wandering star."

As Carr later noted in his reminiscences, which he published in 1807 as

A Tour through Holland, the "aqueous kingdom" impressed him as happy and prosperous. Her stone houses he found "very noble"; her streets, broad and magnificent. Dexterous were her boatmen, and beautiful were her women and cathedrals.

More than any fluttering eyelashes or flying buttresses, what impressed Carr about Holland was her food. During his tour he ate "exquisitely flavoured" melons, beer and gingerbread. In markets he found fruit "abundant, very fresh, and fine" and "remarkably excellent vegetables ... submitted to the eye in the cleanest and most attractive manner." Potatoes tastier than those grown in Ireland he sampled while traveling the countryside. When strolling in cities he noshed "little rolls and small birds, and slices of cold baked eels," and at table he enjoyed "Rhine crabs, excellent grapes, and a variety of other fruits ... as well as the most delicious bread." And lest he leave that aqueous kingdom without having tasted the bounty of the sea, "nearly fifteen sorts of fish, exquisitely dressed" were served him at the home of one of Rotterdam's most respected Jewish merchants. These delights Carr took as evidence of the "successful inroad upon the physical order of the universe" the Dutch had made.

Still Life with Oysters, a Rummer, a Lemon and a Silver Bowl (1634)

Appreciation for that success didn’t begin with Carr. "In the last age," another British travel writer wrote in 1772, "it is certain, that there was no place comparable to Holland." Indeed, almost the entire 17th century was for Holland a time of satiety and satisfaction. Everyone seemed to have what he wanted from life

"[T]here is no race more open to humanity and kindness or less given to wildness or ferocious behavior," remarked Erasmus of the Dutch. Such graces he attributed "the wonderful supply of everything which can tempt one to enjoyment."

. Bread riots were as rare as the prized Semper Augustus tulip

By 1636 the tulip bulb became the fourth leading export product of the Netherlands, after gin, herring, and cheese.

, happening a mere four times in some 100 years. To a continent otherwise plagued by violence, depressed wages, famine, and dearth, Holland represented an oasis of peace and plenty. Her troubles fleeting, her affluence enduring, she gave her people a lot to be thankful for.

"Centralised authority had effectively crushed all minor extortions and violences. The lords of the soil had imperceptibly passed from the turbulent heads of clans into proprietors of land to let for rent in money, labour, or kind. Private war no longer wasted the fields of the husbandman or the wealth of the burgher." --W. Torrens McCullagh, Industrial History of the Dutch (1846)

The Dutch owed their good fortune, as noted as early as the 15th century by Erasmus, to "the ease of importing goods and ... to the natural fertility of the region." This continued to hold true in the 17th century. Much of the country’s prosperity depended on grain imports. Control of Baltic Sea shipping lanes allowed the Dutch to dominate the production of wheat and rye in Poland, East Prussia, Swedish Pomerania, and other countries. Thus they enjoyed not only economic security, but food security as well. Their surpluses they managed with skill and forethought. Grain warehoused in cities throughout Holland served to ward off famine. Such sound provisioning, combined with cheap energy from peat and windmills and thriving financial and colonial interests, made Holland appear an uncommonly blessed nation.

Still Life with Prosciutto and Mug (1631-4)

Evidence of this blessing, as Carr discovered, appeared most visibly at table. Another British traveler noted that the Dutch were "epicures in fish." They could choose from plaice, dabs, flounder, haddock, cod, turbot, and mussels, to name only a few.

Many Dutch found mussels unpalatable.

"These mussels stay always closed / Except for mine which stays always open." --Koddige en Ernstige Opschriften (1685)

So plentiful were finny foodstuffs that they were often thrown away or "sold to the poor for a trifle." Meat came nearly as cheaply. Those low on the social ladder enjoyed ham and bacon weekly as complements to a steady supply of seafood, and in autumn households headed by men in the trades bought an ox or pig, which, once slaughtered and butchered, rendered enough cured meat and sausages to see them through the winter.

Jacob Gillig, Freshwater Fish (1684)

To round out the Dutch diet were butter, Gouda and other sweet-milk cheeses, and fruit and vegetables. Everything from parsnips to cucumbers could be gotten with little trouble thanks to a robust farming industry and a complex system of canals that made bringing vegetables to market relatively easy. Pears, plums, nuts, and apples grew in vast orchards situated on the outskirts of Holland’s cities. The Dutch so loved their fruit that they deemed no breakfast of soured cream complete without fresh cherries. Meat dishes, pies, and cakes they crammed with dried apples and plums.

In northern Holland traveling wool merchants were made to drink without stopping from a quart flagon in which a coin had been tossed. If a merchant emptied the pot and caught the coin in his teeth, a deal was struck and he got to keep the coin. If he didn't empty it, he kept the coin but lost the deal.

Much surplus produce found its way into various brews and distillations. Fresh herb and fruit infusions made beer go down all the better. One recipe might call for marjoram and rosemary; another, plums. Yet even when unembellished by such additions, the Dutch drank beer constantly. Warm beer to which was added sugar and nutmeg served as a morning cuppa for folks who couldn’t afford coffee, and warm beer to which was added brandy, egg, and sugar fortified farmers for the day’s labor.

Willem Kalf, Still Life with Aquamanile, Fruit, and Nautilus Cup (1600)

“A good prince will tax as lightly as possible those commodities which are used by the poorest members of society: grain, bread, beer, wine, clothing, and all other staples without which human life could not exist." --Erasmus

Indeed, Holland developed into such a cornucopia that hunger no longer followed as a consequence of dearth but of maldistribution. There evolved, then, laws and customs to ensure everyone received his share. To students of Leiden University, for example, were decreed generous portions of meat to support their mental exertions. To their professors legislation reserved turkey, jugged hare, Westphalian ham, mutton, veal, anchovies, and, to wash it all down, wine. Pay offered sailors by their captains often came in the form of food. Each week at sea would net a seaman half-pounds of cheese and butter and a five-pound loaf of bread. Officers earned double this. Members of the goldsmith's guild at Dordrecht regularly transmuted the metal of their trade into ham pastries, roast suckling pig, sweet pies, and wine.

Conventional wisdom held that all work and no play made Jaap a dull boy, as well-fed as he might be. Food figured as prominently in leisure as it did in labor. Just about any event the Dutch saw as fit occasion for a feast -- a child's first day at school, an apprentice's first day at the work bench, the latest lottery, the latest lottery winner, a ship's return to harbor, the passing of an illness, the purchase of a new home. Sometimes they feasted simply for the sake of feasting.

Abraham van Beyeren, Banquet Still Life (ca. 1660)

"Wealth would be wealthier still, and aye to gold aspires. / Wealth! wouldst thou wealthier be: diminish thy desires." -- Jacob Westerbaen

High times did breed low opinions in some minds, a few of which belonged to Holland’s literary luminaries. Worried that the rich cream of Dutch life might curdle, poet Jan Krul observed that "an overflow of treasures afflicts the heart and buries the soul in the deepest travail." "[S]mothered and softened from such an overflow of goods" is how the dramatist Vondol described the Dutch capital, Amsterdam

"Adversity makes men, and prosperity makes monsters." --Victor Hugo

. Such criticisms suggest the guilty consciences of those who made them. They perhaps knew that the bounty enjoyed in Holland so defied the nutritional norm in Europe as to appear fantastic. The average 17th-century European made due with bread, water, some onions, and the odd apple. Any rain falling on the plain in Spain brought forth mainly grain, apparently: Cereals made up some 80 percent of the Iberian diet. In terms of variety to their fare the French fared little better. The average working man in Paris is said to have eaten daily over two pounds of bread; his counterpart in Gascony ate virtually nothing besides millet gruel.

Holland must have seemed a veritable land of Cockaigne, a fabled realm whose streets were paved with sausage and whose houses -- made of gingerbread, naturally -- were supported by codfish planks. Yet no matter how prosperous Dutch burghers became, they never forgot the poor. In their concern they stand in stark contrast to their nemeses, the British, who would eventually supersede them as an imperial power.

England's Poor Relief Act of 1576 established the principle that if the able-bodied needed aid, they had to work for it.

The Dutch subjected their poor to no workhouses and the rigors of overwork and near starvation

Dutch prisons were not nearly so pleasant. Incorrigibly idle inmates were punished with the "water house." Jean de Parival offers a contemporary (1662) description of this ingenious punishment: "If they [the prisoners] do not want to work they are tethered like asses and are put in a cellar that is filled with water so that they must partly empty it by pumping if they do not wish to drown."

. They housed them in charitable institutions that were anything but Dickensian. An individual residing in one Leiden municipal poorhouse would be greeted in the morning by buttermilk and two slices of toast. For lunch he might have vegetable soup, meat stew, poultry, mashed vegetables, sweet milk and butter. In the evening were again buttermilk and toast accompanied by cheese or mashed vegetables. If he happened to be ill or somehow enfeebled, he could expect a pleasant supplement of fresh fruit, soup, and, perhaps most welcome of all, red wine. A person wishing to starve in Holland had to work at it. "A Dutch beggar is too wise to waste his breath by asking alms of a Dutchman, and that relief is only sought from strangers," Carr observed. "The fact is, there are so many asylums for paupers, that a Dutchman acquainted with the legislative provision made for them, always considers a beggar as a lawless vagabond."

Willem Kalf, Still Life (ca. 1650)

"He buys honey dear who has to lick it off thorns." --Dutch proverb

Recipe for "Schiedam Schnapps" from Dr. Chase's Recipes (1902): "It is generally known that in Schiedam, Holland, they make the best quality of Gin ... [To make it take] gentian root, 1/4 lb.; orange peel, 1/4 lb.; puds, 1/2 lb.; (but if this last cannot be obtained, poma aurantior, unripe oranges) or agaric, 1/4 lb.; best galangal, 1/4 lb.; centaury, 1/4 lb. -- cost, $1.20. Put pure spirit, 10 gals., upon them and let them stand 2 weeks; stir it every day, and at the end of that time put 3 gals of this to one barrel of good whiskey; then bottle and label."

Such equitable provision was the natural outgrowth of the humanism that influenced Dutch life. Historian Simon Schama notes that at "the center of the Dutch world was a burgher, not a bourgeois." The distinction is subtle but important. "For the burgher was a citizen first and

homo oeconomicus second," Schama continues. "And the obligations of civicism conditioned the opportunities of prosperity." The ample, if not excessively refined, diet prescribed by humanist doctors and divines as nourishment for body, mind, and spirit must extend to every individual possessed of these things, the thinking went. Failing to do so may well have meant that civicism would vanish and, with it, prosperity. So much debate in contemporary politics turns on certain dismaying trends -- a vanishing American middle class, failing public institutions, flagging civic engagement. Meanwhile, corporations sit on billions of dollars in profits that they've sheltered from taxation. Perhaps it's high time that they set about reversing these trends by going Dutch with the public.