By Tamara Fernando

It is the late 19th century, the Industrial Revolution is at its height and Great Britain’s empire stretches over a quarter of the world. New transport links procure raw materials for factories in London churning out mass-produced goods; hundreds of workers perform repetitive tasks that produce lackluster objects; cottage industries are on the verge of collapse. This was the backdrop to the Arts and Crafts Movement — the collective actions of architects and designers on both sides of the Atlantic against the perceived degradation of art by industrial capitalism. One of the movement’s key figures, the designer William Morris (1834-1896) proclaimed, “Apart from my desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life is hatred of modern civilization.” Associating “modern civilization” with rapacious capitalism, the movement turned to the past for alternative modes of production, thus, reinvigorating trades including bookbinding, glass-making, metalwork, and weaving.

Notably, the movement accommodated many women, especially in rural areas and in trades such as spinning, lacemaking, and weaving that had long been gendered. On first appraisal, the practice of women weavers may seem anachronistic as a trade that stands in sharp contrast to modern technology and science. In part, this notion was self-propagated by those within the Arts and Crafts Movement, as the self-taught weaver Ethel Mairet (1872-1952) wrote in her first book, “Dyeing is an art; the moment science dominates it, it is an art no longer, and the craftsman must go back to the time before science touched it.” However, beyond this self-styled dichotomy, a picture of relentless experimentation thorough scientific knowledge and careful innovation emerges, forcing us to reconsider what constitutes technology.

Over the course of her career, Ethel Mariet wrote several books and articles and established a major workshop in Ditchling known as the “Gospels.” She was the first woman to be awarded the Royal Designer for Industry accolade in 1938 and was dubbed “the mother of English hand-weaving” by the Japanese potter Shoji Hamada. Her early life mirrored that of other Edwardian women: she had no formal education and worked as a piano teacher and governess. When she was 30, she married the Anglo-Ceylonese geologist, botanist, and later art historian Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy. The couple soon left for the Colony of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) where Coomaraswamy was conducting a mineralogical survey and where Ethel Mariet would find her passion for weaving.

Art from overseas played a role in trends in London as objects from Japan, India, and Persia were touted as exotic foils to low-quality English goods. The often-violent expansion of empire enabled this as items were acquired as diplomatic gifts or collected on the overseas tours of colonial officials and explorers. Influenced by these anti-industrial trends, the Coomaraswamys similarly toured Ceylon in search of traditional crafts, though they worked with and learned from local weavers. Ethel Mairet became particularly interested in textiles and dyes and even invited local weavers to work in her garden so she could photograph and observe their technique.

A year after the Coomaraswamy’s 1907 return to England, they published their observations in a landmark volume on early South Asian art history, Mediæval Sinhalese Art, which contains passages devoted to weaving. The book also catalogs local dyes, describing, for instance, how the plant patangi was boiled for three days to obtain brilliant reds. Although Ethel Mairet captured, cataloged, and developed hundreds of photographs in the text, the book bears only Ananda Coomaraswamy’s name as an author. A year after publication, Ethel Mariet was working at her first loom.

IMG. 1 Black-and-white photograph of a spinning demonstration at the Whitechapel exhibition, Accession ID: 2002.21.54, Managed by the Crafts Study Centre.

Although Ethel Mairet’s decision to become a weaver fit within a broader revival of hand-weaving in the British Isles, her approach was distinct. Her interest in color, for example, derived from South Asia. In a letter sent in 1909, she wrote to Charles Ashbee about “the hatred that stirs up in me” on encountering “Anglo-Saxon in contact with color.” Ethel Mairet’s particular embrace of color was underlined by a neighbor, Mary Hill, who remarked on how the textiles produced at her workshop were, “almost unbelievable after [the] machine-made and dull material in the shops at that time.” By 1920 Ethel Mairet established what would become her major workshop called the Gospels. Over the next three decades, more than one hundred young women from the UK, Denmark, Switzerland, and Finland passed through the Gospels and learned to spin yarn, dye fabric, and weave.

In 1917, Ethel Mairet published A Book on Vegetable Dyes, a dyeing manual that ran through nine editions. It reads like a hybrid between a botanical guide and a chemistry manual, demonstrating the overlap of Ethel Mairet’s trade with chemistry and botany, knowledge she likely acquired in part from Coomaraswamy, a botanist, and her father, a chemist. Within the text, plants were classified by common and scientific names in groupings by color: an entry for “plants which dye red” included “Birch. Betula alba. Fresh inner bark,” “Bed-straw. Gallium boreale. Roots,” and “Common Sorrel. Rumex acetosa. Roots.”

Once the plant was sourced, the scientific and technical endeavor of extracting the dye and applying it to fabric began. Many fabrics had to be treated with a mordant (from the latin, modere, to bite) first in order to receive color. For the preparation of a solution of hydrosulphite for an intermediate step when working with indigo, Ethel Mairet explained, “Take 2ozs of well pounded indigo, with enough warm water (120 F) … Empty into a saucepan, capacity 1 gallon. Take 12 fluid oz., of water adding gradually 3ozs. Of commercial caustic soda 76 per cent. This will give a solution of SG 1.2, which can be tested with a hydrometer reading from 1000 to 2000, the 1000 representing SG 1 as for water.” This single step highlights how dyeing involved preparing scientific compounds, using precise weights, making calculations and using scientific instruments such as the hydrometer.

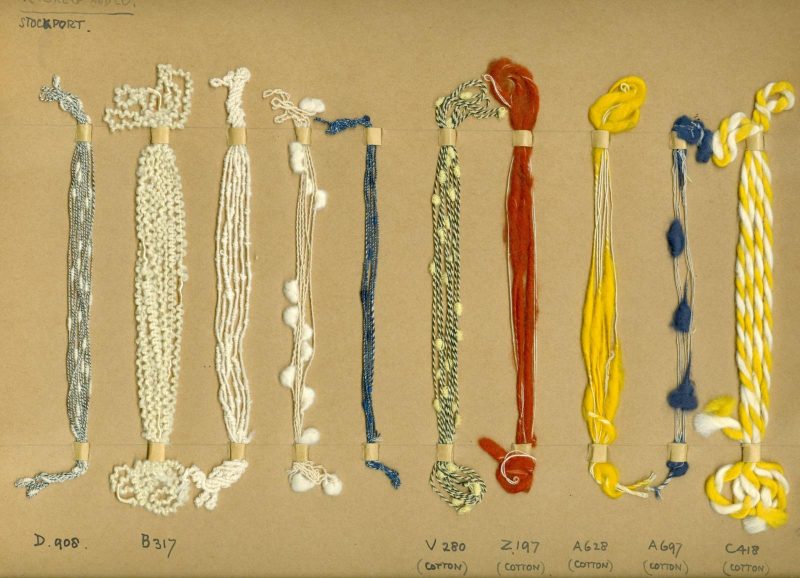

IMG 2. Ethel Mairet, Yarn samples on card, coded by Ethel Mairet, Ethel Mairet Textile Portfolio, Accession ID: 2002.21.34, Managed by the Crafts Study Centre.

Ethel Mairet also had to be familiar with the technical properties of her cloth. In Hand-Weaving To-day (1938) she explained that a weaver must possess knowledge of the “biotechnics of the raw materials.” She went on to describe wool in microscopic detail explaining, “In section, magnified, a wool fibre is seen to be constructed of central canal-like cells, surrounded by elongated cells, with an outside covering of horny scale-like cells.” A continuous innovator, she started with wool and integrated silk and cotton, followed by cellophane and even hair from her dogs (the last experiment failed).

Weaving also required specialized skills to operate machinery. Weaving is the process of interweaving threads, holding one set immobile vertically (the warp) — using tension created by the weaver’s body (as in a backstrap loom) or by a stationary frame — and passing another mobile section through this grid horizontally (the weft) back and forth to create patterns. Although this technology seems outdated, that view only holds if we see technological progress as narrowly teleological, a linear process of perfect replacement, rather than a jostling cohabitation of old and new, applied to serve particular aims.

In Hand-Weaving To-day, Ethel Mairet wrote, “[Weaving] has more responsibility to the machine than any other craft.” This machine, the loom, varied in complexity; for instance, a loom could include a shaft operated with foot paddles or handle-operated levers to mechanically assist in lifting selected threads to allow the weft to pass back and forth, thus, speeding up the creation of more complex patterns. The simplest frame might have one shaft, but the Gospels had four shaft looms as well as two new eight shaft looms imported from Denmark. Both the assembly and the operation of these machines required expertise. One student, Bianca Wassmuth, was admitted to the Gospels because she was able to answer “Yes” to the question “Can you tie-up an eight-shaft countermarch loom?”

Ethel Mairet only had a small commercial base. Despite showing in London and at regional exhibitions, her influence was limited, and she focused mostly on teaching. Her biographer, Margot Coatts, evaluates her place in the Arts and Crafts Movement as “small but singular.” Despite this, Ethel Mairet’s practice provokes important questions about what we consider scientific or technological, and what kinds of labor we value.

For some, technology may conjure up images of circuit boards and steel rooms full of male engineers at machines. This masculinized space is often pitted against its presumed antithesis — the warm, domestic, and feminized world of craft. But this notion of technology divorced from art and craft is of relatively recent origin. Ethel Mairet’s practice, dependent on chemistry, botany, and biology, shows that the two categories cannot so neatly be parsed apart. Craft once held a central place in discourses on technology. The modern Latin term technologia combines the Greek roots logos (discourse) and tekhne (skill or art), and in 19th-century English (unlike in continental languages), technology referred to a field of study concerned with the practical arts, not industry. The Century Dictionary published in New York in 1911, defined technology as “that branch of knowledge which deals with the various industrial arts; the science or systematic knowledge of the industrial arts and crafts, as in textile manufacture, metallurgy, etc.” If technology was the application of skill towards a particular aim, then weavers like Ethel Mairet were early avatars of technology, part and parcel of modernity rather than its opponents.

Further Reading:

Margot Coatts, A Weaver’s Life: Ethel Mairet, 1872-1952 (Bath: Crafts Study Centre, 1983)

Elizabeth Cumming and Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1991)

Ruth Oldenziel, Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007)

Tamara Fernando is a doctoral student in history at the University of Cambridge, where she studies pearl divers in the Indian ocean in the nineteenth century. Her writing has appeared in FemAsia Magazine and The Ceylon Chronicle. She also runs a public-interest Instagram for Sri Lankan history @Lankanhistory.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.