At Cyborgology, Nathan Jurgenson wrote a post questioning whether people should express relief that Facebook didn't exist at some time in their past.

Behind many of the “thank God I didn’t have Facebook back then!” statements is the worry that a less-refined past-self would be exposed to current, different, perhaps hipper or more professional networks. Silly music tastes, less-informed political statements, embarrassing photos of the 15-year-old you: digital dirt from long ago would threaten to debase today’s impeccably curated identity project. The sentiment is almost common enough to be a truism within some groups, but I wonder if we should continue saying it so nonchalantly?

I don't know whether this is a truism, at least not in my demographic. Maybe since people know I write critically about Facebook, I tend to be told the opposite: that people wish they had Facebook as teenagers so they could have gotten more out of the high school experience and not felt so isolated and trapped in exurbia (a sentiment Jurgenson is afraid often gets overlooked). I also can't understand how anyone who would say "I'm glad Facebook didn't exist when I was in high school" would rationalize having a Facebook page now. The stakes are much higher for adults in having their pages stalked or strip-mined for incriminating detail; presumably the people who say this have anodyne Facebook profiles that show them going through the motions of politeness and social conformity. (Ooh, sign me up for that!)

If we accept Jurgenson's contention that the relief of no-Facebook-in-high-school stems from the urgently felt need to suppress the anomalies of earlier versions of oneself, it may be that these people truly believe that their identity has reached stasis, and there is nothing to be risked now by having Facebook. But it seems more likely that they believe that adulthood has equipped them with the tools for properly strategizing their sharing so that their identity won't ever slip out of their control, despite the aggressive way Facebook repurposes the content users provide, dictating how it is presented in a timeline and deciding whether other friends will get to see it in their newsfeeds. And then there is the threat of other users wrenching shared material out of context to draw unforeseen conclusions from it, to make a case against the way someone might seem to be otherwise representing themselves. Everything one shares can become fodder for someone else who wants to reveal the sharer as a phony. And everyone is a phony from some point of view.

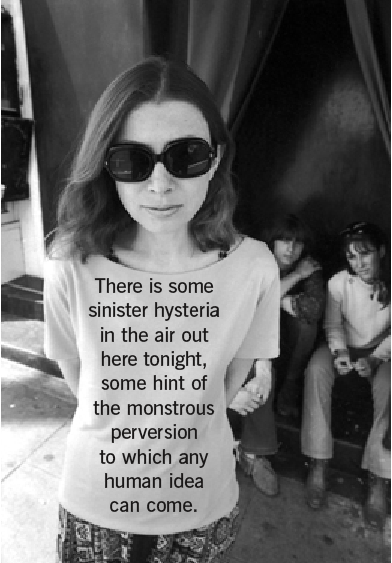

Judging by the image of Joan Didion with a quote from "On Self-Respect" imposed over it that accompanies the post, the remedy for this is a stiff dose of personal responsibility and getting over yourself. If someone is trying to use something you once volunteered freely to humiliate or undermine you, then, well, you had it coming, and you should show some "character" and not take it so hard. It was and is your life, and what makes you think you get to always dictate how you will be perceived? Didion writes,

People who respect themselves are willing to accept the risk that the Indians will be hostile, that the venture will go bankrupt, that the liaison may not turn out to be one in which every day is a holiday because you’re married to me. They are willing to invest something of themselves; they may not play at all, but when they do play, they know the odds.

That's all well and good and "realistic" — life is a game full of risks, no one promised you a rose garden, etc. — but social media have changed the odds in ways that can't yet be figured. It's as though you think you're playing Texas Hold 'Em, but suddenly you learn in the midst of a hand that deuces and suicide kings are wild. The loss of control over what exactly you are risking, and for how long, is what makes social media use so potentially unsettling and what makes people happy that social media didn't exist for long stretches when they were playing the game of life most recklessly.

Jurgenson argues that the relief we feel at not having our earlier selves documented in social media threatens to perpetuate the stigma that he suggests is attached to "identity change" — to experimenting with recklessness, perhaps. Of course, Facebook would like us to think there is stigma to having "two identities," and it is structured to support that ideology. Not only does Facebook encourage us to become a stable, consistent target for marketers, but everything it prompts us to share is attached to a single profile, whose framework is essentially identical to all others. Everything about ourselves on Facebook is reified into the same data form and is subject to the same sorts of response and judgment. (Like!) There is no richer sort of affect captured; instead identity is just a pile of information and a particular network configuration. It can be dynamic only along those two metrics.

So using Facebook runs counter to our lived experience of identity fluidity, code switching, on and offstage separation. Its emphasis on information over presence as the essence of identity muddles the way we are in the world, the sense of control we want to have over adapting to circumstances. It fucks with the degree of autonomy we expect to have over our self-presentation from situation to situation.

People want to have control over that narrative of how they grew up; they want to shape what Didion calls "character" through that story that allows them to stand by what they did. So they are probably relieved that Facebook wasn't around before so it can't serve as a repository now for others to construct an alternative narrative about them or undermine the one they are peddling. We want to tell the story of our own reformation, not stand trial before a jury of our peers, Pink Floyd The Wall–style, and have our defenses torn down. Those defenses shouldn't be stigmatized anymore than the idea of "identity fluidity" should be. (N.B.: I don't think I understand the concept of The Wall. What do the worms represent?)

The problem is not that Facebook exposes how we've changed or that identity is performative in general; the problem is the searchable archive. It's that Facebook stores details about our identity performance as decontextualized information. It encourages the idea that identity isn't embedded in context but is strictly a matter of data. This makes us vulnerable to having our identities "remixed" by anyone who can access the identity information about us and verify we are connected to it somehow. It's as though social media lets people rewrite your diary, forcing you to correct the record with further additions, which can be further remixed — possibly by enemies, possibly by bots or algorithms — until the undermining becomes virtually instantaneous. Then identity becomes a matter of continually shouting your current version of yourself in every possible medium to counter the competing versions.

This is the "alienation from self" Didion warns about at the end of "On Self-Respect," only it is not entirely a matter of being a weak-willed whiner — it's because social media run on self-alienation (turning our identity into information that can circulate) and deny us the ability to put things in the perspective we deem proper. Any given item from our digital record can go viral, can demand from us a different perspective. Didion writes: "To assign unanswered letters their proper weight, to free us from the expectations of others, to give us back to ourselves – there lies the great, the singular power of self-respect." Yet social media are nothing but the "expectations of others" brought to bear on us in a way that sometimes rewards us, sometimes punishes us, and often does both at the same time. Didion's conclusion would perhaps be that no self-respecting person would use social media in the first place. But of course, opting out for most of us is untenable.

The persistence of material shared in social media opens the possibility for a much broader range of doxxing as entertainment — exposing people for their embarrassing earlier moves, when the necessary strategies for gaming life and self-branding seemed different. Everyday schadenfreude for everyone. This is a large part of the reason social media thrive: they are a vector for gossip and drama. They bank on and intensify our impulses toward voyeurism and judgment passing and clique formation; they have little invested in reversing those tendencies.

Maybe it will require only some additional character to deal with the bonus harassment and drama social media by default encourage. Maybe the idea that everyone can blackmail everyone else will make us all more tolerant and somehow more loving of our fellow blackmailers. Maybe it's as easy as telling people, Hey, buck up and be prouder and own what you've done. But collectively, we have a lot invested in the ability to shame other people, often under the flimsiest of pretexts. And no matter how rigorous you are about going Galt and ignoring the approbation of others, social rejection still circumscribes the opportunities one has in life. Doxxing can work no matter how much character you show about it.

It would be great if we all stopped taking the sorts of things that end up on Facebook and Twitter as definitive expressions of identity, of character — if we rejected the idea that user profiles are anything other than places to build equity in the self-brand, which is a managed property very separate from the self. It would be very nice if we did away with the bogus consumerist ideal of personal authenticity that has us trying to curate a personality. But it seems more plausible that people will continue to enjoy the social-media-abetted form of shame entertainment for the same reasons they enjoy it now: It shows other people being punished for having the temerity to try to become something self-willed. If we let them succeed unhindered, then what becomes of our excuse for not making what we want of our lives?