My interview with Peter Galison was published in The New Inquiry’s Shelter issue. Below, at almost double the length of the published version, is the full, uncut text.

___

NEW INQUIRY editor-at-large Maryam Monalisa Gharavi held a long-ranging conversation with historian of science, physicist, and filmmaker Peter Galison. Galison is author of the books How Experiments End, Image and Logic, Objectivity (with Lorraine Daston), and Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps, about revolutionary sciences of the 19th century that portended scientific and political encounters of the 20th century. The interview delves into the last century and its long shadow over the security regimes of the 21st: how military landscapes and nuclear sites, secrecy and paranoia, technology and terror wars, conflict zones and no-zone zones, and materiality and mortality shape contemporary life. If there is one thing that distinguishes the world of yesterday from today, it is that the illusion of shelter and containment can no longer be safeguarded.

Appropriately, the author’s first encounter with Galison was in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon blast. Galison is distinguished not only by his keen investigations at the border edge of physics and scientific experimentation, but science’s relationship to art and art’s claims to objective truth. At the time of the interview, his collaboration with South African artist William Kentridge Refusal of Time opened at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Galison was a 1996 MacArthur Fellow and a 1999 Max Planck Prize winner. He teaches as a professor of physics and history of science at Harvard University; the conversation took place at his office.

Maryam Monalisa Gharavi: Where did you grow up? What were you reading and doing? What led you to physics and science history?

Peter Galison: I grew up in New York City. Most of my family was much more interested in the arts than science. My great-grandfather—who lived till he was almost 100—had worked in Edison’s laboratory at the turn of the century. I knew him quite well—he lived till I was 15, 16 years old. He had an electrical engineering lab in New York City and I would go visit him. That made a huge impression on me. These beautiful double pole switches, arcs of electricity going between poles. He turned his own screws on a lathe. Bottles of mercury. He could blow glass. It was a kind of late-19th century German, or Edisonian, lab. It left a huge impression on me. Most of my family was much more oriented towards literature and the arts. Both of my parents had had art training, both of their sisters had been artists. That was probably more in my immediate world. The other really important thing for me was I grew up in the Vietnam War time. I was younger than the ’68 generation but I grew up knowing them. New York City was full of demonstrations.

I would hang out at bookstores in the Upper West Side and talk to graduate students there and they would recommend things for me to read. I read a lot of philosophy. I did a lot of physics in high school and I took a more advanced course at Columbia. So I had a lot of exposure to different strands of thinking and in a very agitated, upsetting, intriguing, and formative environment. Politics were always everywhere. I was studying physics. I loved physics! But at the time, no one of my peers in high school would come close to physics. I used to come back and talk to the teacher—I had good physics teachers—and it was like getting samizdat lessons because for many of my friends physics was one step off of plastic shrapnel. There was nothing appealing about it. There was a very strong anti-science inclination among people who I knew who were, like me, rather concerned about politics and worried about Vietnam and Cambodia and Kent State.

It was one thing after the other every month. I got a couple of years ahead in my studies. I didn’t want to come to college that young. So I went to Paris for a year and worked in a wonderful laboratory at École Polytechnique. I took a course from a terrific mathematician named Laurent Schwartz. But if it was possible, Paris was in even more turbulence than New York. There were riots and demonstrations every day. There was a bookstore I would go to every day where people would have discussions. One day it would be political interpretations of Kafka, and the next day it would be the debate between the seven most active Trotskyist parties about who had the right line! And Maoists fighting with fascists on the street. It was pretty wild.

But it meant that I read very widely. I had a French teacher who had done his graduate work in French literature at Yale. He had left teaching the same year I left high school and he was also in Paris with his French wife. I used to go and talk to them and they’d give me books to read. So I was talking to them and reading a lot of Proust, new French novel—Michel Butor and things like that. A lot of the kids I got to know in the preparatory schools—equivalent to the first two years of American university—were in philosophy and I talked to them a lot. I read the things that they were reading. They were very interested in cinema. I knew very little about cinema when I went there. I’d be in a movie theater and people would say, What do you think of recent Czech cinema? So I felt like I should have a view about that. I would go to the cinemathèque and see every film made by a certain author and we’d come back at four in the morning. It was a real kick for me—I loved it and I was sort of soaking up a world I hadn’t known in so many ways. I did a lot of physics and math and then I’d say mostly philosophy but in a kind of giant heap bath of politics.

So did college stop the fun?

Well, I was an undergraduate at Harvard. I started as a sophomore in 1973 and that was still the end of the Vietnam War era. The first time I came up to Harvard I was 15 or 16 for an interview. Wigglesworth had just been tear-gassed and Harvard Square was filled with it. It was a wild time. Seventy-three was still a part of the long Sixties and I didn’t know—I originally thought that I was going to study a combination of mathematics and art, actually. I remember I talked to the artists and they thought this was a great idea and I went to the applied mathematicians and they said it was the worst idea they’d ever heard. I didn’t really know what to do. I was a little stymied.

I was enrolled in some advanced courses in math. I had one course I very much liked, a sort of more technical course than now called Math 55 and there were only a couple of students in it and some very good mathematicians. Bill Gates was in my class. Jim Sethna who’s now a professor of physics at Cornell, and lots of other people. It was a very intense course, and I liked that. I took a course from Roberto Unger who still teaches at the law school and whose work in social theory really interested me. I took some classics in translation—I don’t and didn’t know Greek and Latin. I took some philosophy and ethics courses—I took one from Miles Burnyeat who was visiting from Cambridge, one of the deans of classical studies—on Nicomachean ethics. I had a great time! I was a kid in a toy story. I really liked being able to pursue these things. But I didn’t know exactly how to combine my interests in the humanities and the sciences. That remained urgent to me back then as it is now. There was never a time when that wasn’t a part of what I wanted to do.

And then I found history of science. I read Thomas Kuhn’s book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, and Gerald Holton’s book The Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought. I had read a bunch of philosophy of science—I had read Quine back in high school and I was interested in that. Everything was a little out of context—I didn’t have much background or surround. It was kind of helter skelter at first and gradually became more systematic.

After Secrecy (2008) you and filmmaker Robb Moss began working on a film about nuclear waste in Nevada. What did you discover and what can we expect?

My interest in general is the way physics—broadly conceived—relates to other domains. I think what’s astonishing about physics is that it occupies a territory that on the one side is linked to the most practical, consequential issues of nuclear weapons, nuclear power, vast industries of radar and military equipment, civilian electronics, and so on. On the other side, very longstanding philosophical questions about the nature of causality, what is time, simultaneity, how do you understand the origin and fate of the universe—these very abstract questions. That sudden juxtaposition of the highly abstract and the highly concrete is what interests me most in the world, and physics seems like a good way to get at it, for me.

This film that Robb Moss and I are finishing now is called Containment. It’s about this necessary and impossible problem of containing nuclear materials for the very long term. Plutonium has a half-life of about 24,100 years, which means that it’s half as radioactive in 24,100 years as it is when it’s created. And we’ve created a lot of this stuff. So where’s this all going to go and how can you stop it from getting out in a period much longer than human civilization? We have a huge legacy of nuclear waste from the 70,000 or so nuclear weapons that the United States produced and that the Soviets produced in equivalent number. Every country that has a nuclear weapons program has a vast quantity of nuclear waste. Then there’s nuclear waste that comes out of nuclear power. And every nuclear power plants discharges spent nuclear fuel which is much more radioactive than when it enters the plant. So what are you going to do with it?

In famous incidents like Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear fuel accidentally and explosively entered into the environment and we’re desperately trying to keep it from spreading. So we have to deal with it and yet it’s unbelievably difficult and expensive. And that combination—of it being necessary and impossible—is completely riveting to me. It forces us into a domain that really makes us question very basic things about our world. What are our obligations to hundreds or even thousands of generations into the future? Should we dispose of things in a way that’s completely inaccessible or should we give each generation a chance to intervene in new and technologically more sophisticated ways? Countries disagree about that. People within our own country disagree about that. What are these lands that are nuclear contaminated? One nuclear factory that we’ve been filming (the Savannah River Site) has a whole biological branch which biologists there identify as the most biologically diverse site in the eastern, maybe whole, United States.

But would you eat a tomato there?

You better not eat a tomato there. You better not eat a turtle there! People in the southeast eat turtle and alligator meat and there are radioactive alligators and radioactive turtles. So it raises these very hard questions and I like that.

I’d like to talk about two articles of yours from the early millennium, “War Against the Center” (2001) and “Removing Knowledge” (2004). I think they’re incredibly important pieces of work. In the first, you pose the question of how we departed from centered modernism to aesthetic, architectural, even metaphysical placelessness. But you seek the answer not in the oil crisis, economic downturn, literary theory of the 1960s, or even the Internet but in “bombs of the long war.”

Well, one of the things that really struck me is how we have a certain idea of how the self—the collective self or the individual self is formed—and that leads us to build certain kinds of technology. And then those technologies then act back on us and transform that self in certain ways. One example is that during World War II there were thousands of people in the United States and in Britain thinking about how to bomb. They thought they could stop the Nazi war machine by figuring out a key linchpin—that if you pulled out that linchpin, if you destroyed that one thing—the whole apparatus would stop.

There were times when it was thought to be oil, ball bearings, and various other theories of what that linchpin might be, but it was predicated on a picture of a kind of collective self, a city as self, that was based on an almost human body. If the heart stops body the whole body stops living. This had been deeply woven into the way bombing was conceived and cities were conceived in the 1920s and 1930s when the idea of bombing from an airplane became a reality. There were thousands of people—representatives of the oil industry, the ball bearing industry, the steel industry, and so on—and that each of them was asked the question, “What would stop your whole industry from functioning?” And then figuring out what the analog was on the Nazi side and bombing it. That was the idea that founded strategic bombing in the war, with devastating consequences. But then after Hiroshima and Nagasaki when the American evaluation teams went over to the bombed cities in Japan and their first question was, “What does this mean for our cities in the future?”

Right. It wasn’t until the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey investigators began to see a resemblance between buildings, structures, and shelters in Japan and ones in the United States. There is a major historical moment when the American elite begins to see itself in the destruction it has caused and begins adjudicating the need to decentralize large American cities and commit to what you refer to as defense industrial dispersion. You wrote, “They began, quite explicitly, to see themselves, to see America, through the bombardier’s eye.” Did it surprise you to discover that it took an actual social practice of training Americans to see themselves as vulnerable—and resembling others’ vulnerability—amid the regular activities of profits, markets, and the like?

It proceeded in several steps. During the war, the Germans dispersed industry so that all the Messerschmitts were not all built in one place. They would build the wings in one place, the fuselage in another, parts of the motor in one place, and the final assembly in another. The Germans were quite successful at continuing industrial production until late in the conflict, because of this dispersion. That didn’t really register at the highest levels of Americans’ thinking of our own cities. Until Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And then the sudden idea really came home. This could be our cities. This could be us on the wrong side of a nuclear bomb. When that happened they looked back at what happened, in Germany especially more than Japan, about industrial dispersion. Then comes the crucial step: They began to try to train American city planners and industry leaders, in fact, distributed grids that were clear plastic targeting sheets over the maps of the cities that would teach you how to create a score that would tell you how effectively dispersed your city, industry, and population centers were. It’s at that moment that this goes from being a discussion among a rather small groups of experts—industrial and population centers, targeted evaluation teams, and so on—to being an ordinary city.

We learned to target ourselves as a way of anticipating how we would look targeted by the enemy. It really is a practice. It’s laying these sheets over a map of the city with radial distances and a scoring mechanism giving a number to how dispersed your city and industrial and population centers, and giving money—tax credits—to ensuring that dispersion. We have an idea of the city with a centered entity with organs that are like a target—when police or soldiers are learning how to shoot at a target of a human silhouette there’s different zones—and this idea that there’s a sort of fatal zone here and a non-fatal zone there was partly how they conceived of our own cities and industries. Then that was projected onto the enemy.

By the end of the war the enemy became a model for how we should think of ourselves at the pointy end of the stick. That led to this training ourselves to being a new way, to conceive of a city in its dispersed form as the ideal rather than the centered form found earlier. There are other things that push our cities towards dispersion, and I don’t mean this to be reductive, but it was intensely interesting to see how this worked. I mean, there’s returning soldiers, the GI Bill, suburbanization, new roads, the breaking up of trains, the rise of trucking, lots of other things going on that are encouraging dispersion. But that reciprocal action—building an enemy in the understanding of ourselves and rebuilding ourselves based on what happened to the enemy—is very important, I think.

If the mid-century sees the effect of cities like Gary, Pittsburgh and New York and Chicago mirroring their enemy cities in Berlin and Nagasaki and Tokyo—you acerbically call this a “Lacanian mirroring”—what happens in the following decades of the 70s and 80s? The 50s and 60s foreshadow a very technically advanced enemy. How consistent is the U.S. government’s position of assigning power and advanced capabilities to its enemies?

You could think of a single long war that goes from the 30s through the 80s. The enemy changed from Nazi Germany to the Soviet Union and its allies. But it was a mirror war. Whether it was the hot war of World War II or the Cold War to follow, it was predicated on an enemy that was built much like us. In the Cold War, we had nuclear submarines with nuclear-tipped missiles and the Soviets had nuclear submarines with nuclear-tipped missiles. We had main battle tanks and they had main battle tanks. Each time one side would get an advantage—we had a language in the Cold War that was encouraged in the time of Kennedy, and even before, of the “gap.” If they had more missiles then we had a missile gap—

And reciprocity—

And a gap and reciprocity leads to a kind of mirror world. Luckily we didn’t destroy ourselves. But instead formed an unstable equilibrium where everything that existed on one side existed on the other. The assumption was that the other side acted in ways similar to us or would respond to threats the way we would respond to threats, and that this would somehow stabilize the world. Game theory came into play here where we actually began to quantify and make a science out of the study of this. Everyone could imagine that they had a counterpart. We had nuclear scientists, they had nuclear scientists. We had plutonium plants, they had plutonium plants. We had naval yards, they had naval yards. They didn’t want to die, we didn’t want to die. What happens at the end of the Cold War—more than I think the ’70s and ’80s—is that the Cold War begins to come apart as the Soviet Union comes apart. You don’t have these mirrored sides. I remember this moment in the early 90s hearing senior figures from the military and politics saying asymmetric warfare is what’s going to be happening. Nobody exactly knew what that meant. But it meant there wasn’t going to be a replacement, a third term in the relationship—Nazi Germany, Japan, the Warsaw Pact—it was going be something else. Maybe it was going to be guerrilla warfare, or terrorism, but it was going to be something other than what we had experienced. The successor to the long war is the terror wars. That is where things begin to disequilibrate from that regime that we were discussing.

While you were pointing to this tripartite enemy I was thinking of the “Axis of Evil,” although it too was displaced onto Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen. But I wanted to ask how you digest today’s imagined technocratic enemy. On the one hand, people are inculcated to perceive foreign threats and promises of threats. On the other, the White House approves the drone bombings of sheep farmers.

The Axis of Evil is interesting because it seems to me that there was a tremendous internal drive to finding a successor to the Soviet Union that would be like it, that would have a mirror reality. There was a moment on September 11 2001 when the pilots were mobilized from here, from Otis Air Force Base on Cape Cod. They arrived over Washington and they were looking for cruise missiles. But there were no cruise missiles, right? If you said the United States is under attack, which it was, it was not because there was a country that was a successor element to the Soviet Union. It was a kind of phantom limb of an earlier mirror stage of warfare. The idea that they were looking for commercial jets was inconceivable. Right around then Condoleezza Rice was preparing to give a talk on the Russian successor to the Soviet Union. Everything was prepared for the continuation of what I was calling the long war. It was very hard to give that up.

The Axis of Evil didn’t survive as a guiding concept for military planners, politicians, academics. It was dropped out of conversation. It really was a phantom limb that never was there as such. Which isn’t to say there aren’t enmities among states but not that way. Not an axis like the axis of 1938, that doesn’t exist. What’s happened since then is a very different kind of concept, one where the whole idea of a target is completely dispersed in a much more dramatic form than anything imagined by the Cold War planners who were moving industries to the periphery of cities, for example.

Now, everything is a target. Not only a target for us but a target of how we imagine our own societies. Every mall is a target. Every telephone switchboard, every gas or oil refinery, every school, every dam is a potential target, every monument is a target. You can now classify infrastructure—you know, the water and gas and oil and electricity and information flow—during the Cold War it was never allowed that those things be classified. The concept that everything is a target, both aggressively and defensively, is a very different and to me very worrisome kind of society that brings a whole new set of technologies, of which drones are one, and cyber warfare, and many other kinds of security and surveillance states that we live in now.

In a way the NSA discussions about scooping up all information because all information is potentially revelatory of a kind of attack is a kind of asymptote of that way of thinking. If you think that everything is a possible target—if everything is a target then it’s kind of logical that all the information should be thought of as a potential clue, because everyone, everywhere, all the time is part of this dispersal.

Could one say accurately that the flattening of Iraq, where everything is a target—children’s milk manufacturers, diaper factories—produced a frictionlessness? Has that cast a long shadow on the question of “everything is a target”?

It’s a progression that goes from 2001, which has aspects as I say, of an earlier concept. An attack directed at the United States was directed at a headquarters of symbolic and real power. The Pentagon, the World Trade Center, the Capitol. They still had a residue of an older way of thinking, but very rapidly morphed to something different.

You would see in newscasts in 1943 in American and German cinemas, they would show you the front. In Vietnam, you would take a hill, leave the hill, you would come back and take the hill again. There wasn’t a kind of stable configuration but there was nonetheless an idea of where the conflict zones were, even if they were shifting in an irregular way. But where is the conflict zone now? In a way the question doesn’t even make sense anymore. When you drive into a garage and someone takes a mirror on a stick and looks under your car—I mean, it’s because everything is a target. It’s both aggressive and defensive. It becomes a concept of the world as in a ubiquitous conflict, everywhere and all the time. If you think that, then the response is the one you see: A whole raft of technologies designed for that kind of surveillance.

Take an airport. You go through an airport. People are very aware of the security and getting scanned and putting your knapsack through an X-ray machine. But the surveillance of you as a passenger begins long before you get to the airport. They’re already looking at previous travel patterns and data mining about you. So it isn’t even a point-specific surveillance. I think that’s characteristic of our time. In a way you could see it as an intensification of what began earlier but it has led to a different regime of security, one that I think of as qualitatively different. It begins as an intensification that’s quantitative but at a certain point when you say “We’re gonna monitor the whole of the Internet and archive it and be able to mine it!” that’s a different concept—that isn’t point-specific at all. It’s not just that there are a lot of targets, it’s that we are all targets. Always.

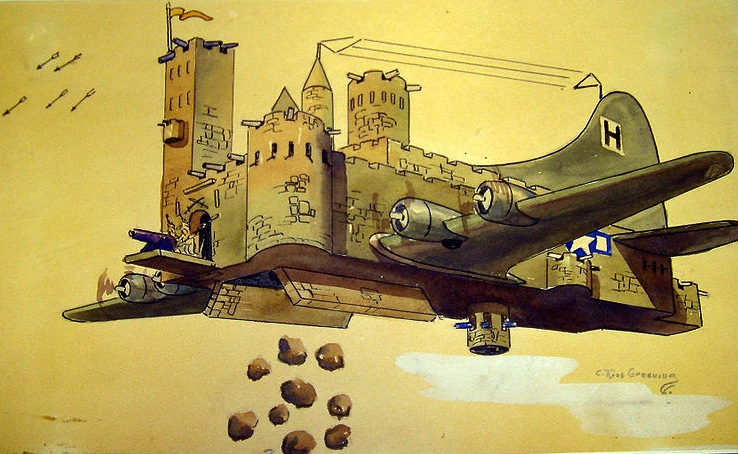

I agree. It’s not just drones or just surveilling passenger’s lists. It’s a completely different structural organism. You anticipated the question I was going to ask. The Strategic Bombing Survey was founded in the same year that the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses were pounding away in Europe. What do you make of the relationship between the oligarchies of the long long war—up to and including the “War on Terror”—and today’s contemporary missile weapons? The long-range Flying Fortresses flew overseas and returned home, even when badly damaged. The drone operating centers of the West are separated by oceans from the killing fields of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Yemen. Then there are the 350 acres of the National Security Agency’s physical site at Fort Meade. Has a novel static fortress been established?

The asymptotic limit of where we are both offensively and defensively is that there are no shelters. There is no fortress. The people flying drones are in trailers. There are air-conditioned trailers on an air force base. But they could be anywhere. It doesn’t really matter. It’s not as if we had the equivalent of Iron Mountain in the Cold War, you know, a mountain in the innermost recesses with nuclear weapons-capable doors, giant steel slabs, and water and food supplies and currency to keep a continuity of government. All that has decayed. It feels antique now. The NSA headquarters is only a piece of the NSA and nobody thinks of that campus as being particularly well-protected in the sheltering sense of being deep in a mountain where Vice President Cheney would go hide deep underground in a suburb of Washington.

You can’t stay in the bunker forever. The idea of a bunker only makes sense for a limited-time conflict, even if that conflict was apocalyptically devastating. So the picture that people had was, The war is short, it lasts for hours or days, there’s an exchange of nuclear missiles, the key people to extend the continuity of government of the United States or their equivalent in Russia would go into these shelters, they’d stay down there long enough for the radioactive levels to subside to a level where they could come out again, and then society would begin to reconstruct such as it could. But nobody thinks that the conflicts that we’re in have a scale of hours or days or weeks or even years. We live in a much more permanent set of conflictual relations. The surveillance and drone systems are not for a punctiform conflict.

Your film seems to be an answer to this question because if we can’t contain nuclear waste, if there is no such thing as a bunker for it—and I just read that the levels of radioactivity in Fukushima are several times greater than those of Hiroshima—then it would almost seem to logically speak to the idea of no more bunkers.

I do think there are no more bunkers. It’s interesting to compare Fukushima and Hiroshima—one has to be careful, but it is interesting. In Hiroshima, the primary radiation takes place—the bomb explodes in a millionth of a second, there’s maybe a couple of seconds of radiation that follow as some of these isotopes decay. It’s exploded 2000 feet above the ground so if you’re hit by that radiation—if you’re not killed by the blast or the fires—the radiation you get was mostly from that initial blast.

One hundred thousand killed in one night.

A lot of what we know about the danger of radiation exposure comes from Hiroshima and Nagasaki because we know quite precisely—if you know where you were relative to the bomb we can calculate how much radiation you got. There wasn’t very much radiation on the ground. If the bomb had been exploded on the ground there would have been a vast amount of fallout, and we had bombs in the Cold War that did that, and the nuclear testing led to all sorts of radiation dispersed all over the world. But not Hiroshima and Nagasaki where bombs were exploded 2,000 feet up to maximize their blast damage. In terms of the residual radiation on the ground Hiroshima was relatively quickly rebuilt and reoccupied. It’s now a thriving city and it has been for decades. The reason for that is that the bomb did not cause the ground to be radioactive. The radiation was entirely in the form of gamma rays—like X-rays only much more energetic—they are dangerous but once they’re produced they’re absorbed and that’s it. They don’t create further radiation.

Fukushima is a very different thing. Of course nowhere near the number of people that were killed at Hiroshima but the amount of radiation on the ground is much higher. Robb Moss and I have been filming in Japan, particularly the cities Futaba and Nanae and other myriad abandoned towns in the hills in the area. It’s because those towns have high levels of radiation. Probably 100,000 were told to evacuate by the government and another 50,000 that left on their own because the towns were—once the doctors are gone and the schools are closed and the economy’s gone, you can’t continue to live there, if you’re a fisherman you can’t fish, if you’re a farmer you can’t farm—so about 150,000 people have left. It’s a kind of ghost area. Some people will say, “People should go back.” How do people go back? Would you go back? Would you, as a young person, or if you had a baby? If you did go back, what school would they go to? Where would you buy bread? How would you earn a living?

What’s interesting in the contrast that you raise is that on the one side, we had bunkers that were protecting us—or some people, not us in general, but some people—from the radiation. These are bunkers to keep the radiation in and away from us. One was saying, we’re going to dig a hole in the mountainside and our leaders will go hide there and direct things until they can come out again, to be safe from the blast of a nuclear attack. Now we’re burying the nuclear waste to try to keep it in. The problem for something like Fukushima is that every attempt to try to contain this waste keeps failing. First they tried to put contaminated water in tanks. Then they tried to use chemicals to make a kind of wall underground to keep the radioactive groundwater from going through. Now they’re talking about building an ice wall, a giant underground system with pipes of liquid nitrogen that will freeze the ground so the water that’s now contaminated won’t get to the ocean. That will surely overflow too. Hundreds of tons of water are going into the Pacific now that are very contaminated. But it could get worse too. And no one really knows—certainly the Tokyo Electric Power Company doesn’t know—how to contain this. It just keeps getting out.

What did the Japanese denizens that you and your crew encountered reveal to you about their deep fears of what’s happening?

It’s interesting. I’ll give you a couple of examples. We talked to an older guy in his 80s whose family has lived in an area near Fukushima up in the mountains for over 300 years. There are trees that his ancestors planted 16 generations ago. He gradually harvests and runs this forest. All the younger generations below him have left, his children, his grand children. Nobody wants to stay. They can’t stay. As I say, there are no schools, there are no doctors. Even he can’t really stay there—he’d like to die there if he could, to live throughout the rest of his life, but there are no doctors, there no hospitals, there’s nothing here. So every other day he drives from his temporary housing to his old house and just sits there because he wants to be in the place that his ancestral home is. He feels it as a terrible loss but it’s the only way forward for him. And he understands that only an older person would want to do that, because if you were 28 with a baby you just wouldn’t.

We talked to a young woman who has children and she’s left. She went back to look at her house and said: I can’t live here. I can’t grow vegetables, I can’t—how’s that going to work? There’s a cattle farmer we talked to who’s really quite remarkable. He had cattle and they were sold for meat, so it’s not a show farm, it’s a real working farm. But a couple of days after the Fukushima accident the government ordered all the farmers in this area to kill the cows. He refused. There are signs that say, WATCH OUT WILD COWS, because there are just cows wandering around the countryside, abandoned. The farmers left, and so he’s gathered all the cows—his and other people’s—and he says, I see this as an act of resistance. I won’t leave. The government’s ordered me to leave and I won’t leave. They ordered me to kill the cows and I won’t kill the cows. You can’t sell the cows, you can’t milk the cows—I mean you can milk them, but you can’t sell the milk—so it’s all valueless in some sense. But he thinks the idea of killing a cow because it lost its monetary value is immoral.

We talked to fishermen, and you know, you see fishermen just sitting in the docks. They test a statistical sample of the fish—we went to the fish-testing factory and some of them have high radiation and some not—but you can’t sell fish. So some of them have been trying to make it a place for deep-sea fishing. But if you want to take a deep-sea fishing vacation and someone said, Well, would you like to go to Fukushima? It’s not a promising economic road. So they don’t know what to do. They’ve been fishing all their lives. The rice is contaminated. At TEPCO headquarters they sell rice from the Fukushima area in the lunchroom. We went there but I don’t know whether the people eat it or not. But it’s served, and there’s a sign that says FUKUSHIMA RICE.

What did you eat?

We tried to be careful but it’s like, you still have to eat. What water do you drink? What do you trust? A lot of food there is very carefully tested but a lot of things are tested statistically, not individually. You can’t test every fish that comes out of the sea. So you test one out of every thousand or ten thousand and you try to get an idea. There are supermarkets that have Geiger counters at the checkout counter in that area. It’s not all of Japan but it’s a much bigger area than I had realized before I went. You drive for a long time going town after town after town that is abandoned. It’s not a tiny area but Japan’s an island country. How this is going to play out in the long run, no one really knows.

The only thing I can compare to this stupefying account is Iraq. My father went on a medical mission there and I went with him. In Baghdad we were forced in our place of shelter to drink from the Tigris. We didn’t know it was the river but the water facilities had all been badly damaged and there weren’t truck coming in with water you could buy. You have the choice to either drink no water or drink water that gives you diarrhea.

When you have areas that are contaminated they enter a new kind of landscape. I’m finishing a book now called Building Crashing Thinking. One of the chapters is called “Wastelands and Wilderness” and it’s about how nuclear wastelands and the idea of wilderness have actually come to converge in certain ways. Instead of seeing it as this great irony I actually think it’s an extension of an idea: identification of certain kinds of lands without us as having a special status. These nuclear-contaminated zones—or “national sacrifice zones” as some people have called them—become what we call wilderness in many respects.

It’s remarkable, not ironic but very understandable, that the most bio-diverse site is a nuclear weapons laboratory because that’s where we don’t go. In the future it may be that we look on at these sites that they don’t seem like the opposite ends of a spectrum that go from defiled to sacred purity but rather that they come together more like a circle, and that the lands are identified by their being without our presence. I think that this concept of waste wilderness, when I try to think about how to identify that and call it by a single name—“waste wilderness”—may be the right way of thinking about these sorts of territories.

That seems to be more prescient than the discourse of permanent endangerment or extinction. You’re promoting the idea of the convergence of the consequences of our actions.

Yes. And you know, I’m neither celebrating nor mourning this. I’m simply saying I think that’s where this goes and in a certain sense where we already are. There’s a category of nuclear tourism that people go to visit nuclear sites. That should be unnerving and give us pause but I think it’s already in motion.

Can you speak to parallel courses of thought in your work on military urbanism and architecture? I am thinking of Robert Beauregard who uses the term “edge city” (coined by Joel Garreau in 1991) as a way Americans resolve a deep ambivalence toward cities. Edge cities as those which peripheralize the urban core, peripheralizing the center. Garreau included Route 128 southwest of Boston as an edge city. You wrote about the 1950s government projects of constructing ring roads around cities and locating defense industries on it—citing precisely Route 128. Can you speak to the work of others that runs analogous to yours?

Much more in America than say in France, geography has left the required structure of education, although it’s reemerging now in many places as a very interesting, exciting domain. You could say it’s always survived. There are a lot of interesting people who think of themselves as part of a new generation of geography. That’s also had connections with landscape architecture, which also had been made more peripheral within the design community and architecture schools, and I think there too, they’ve had a certain reenergized generation recently. For instance I think of at the Graduate School of Design here—

—[Charles] Waldheim—

Waldheim, for instance, and I’m speaking at a conference they’re holding there next month on airport landscapes. That’s not traditionally the study of English gardens. It’s also not just a kind of lamentation over fallen land. It’s actually trying to take seriously what it is to look at the geographies of spaces that were considered to be outside of the natural subject of planning, design, architecture, and so on. That’s very, to me, exciting, and I find myself with a lot of kinship with some of this new work. There’s a group in Europe that I work with a lot.

There is group in Milan and in Finland led by these guys [holds up a publication], Alessandro Balducci and Raine Mäntysalo. They’ve been using another piece of my work that I’ve called trading zones, that for me, entered into trying to understand the relationship between different scientific subcultures that form disciplines like physics, for example, and to say that people can share—I was interested in the problem of trying to get away from a picture of the relationship between scientific cultures that was made very widespread by Kuhn, with the change of paradigms, with a radical shift of language or by Foucault’s epistemic break, where their metaphors were one of religious conversion or radical translation or ships passing in the night or gestalt psychological shift from a duck to a rabbit.

We’ve got a lot of ways of expressing this, but the idea was to break up the idea of a continuous scientific vocabulary of observation that’s sort of built incrementally and progressively and say instead no, it’s like seeing a duck then seeing a rabbit when you go from Newton to Einstein, or something like that. I was never very comfortable with this picture, not because I wanted to return to an older one of aggregative, teleological notion of science, but because it didn’t seem to capture how in fact these communities did talk to one another. I began to ask the question, How do actually different cultures with different languages, for example, in fact talk to each other when they’re adjacent? Instead of pulling out of the air that it’s like going from Chinese to French, saying instead, What really happens in Alsace-Lorain or in the littoral regions of the Pacific, and so on. What happens, as the anthropological linguists tell us, is you form jargons and pidgins and creoles and these hybridized languages that borrow pieces of other languages—the syntax from here and the phonetic structure from there and the semantic structure from somewhere else—and I wanted to look at science that way too.

Biochemistry or biophysics or physics itself were in fact hybrids. They weren’t pure disciplines any more than they were pure languages. English is a hybrid too. It’s not like there are hybrid languages and pure languages in a kind of 18th-century concept of language but I mean, English is obviously a hybrid language. It is a creole. And physics is too. I was interested in how these zones of exchange, where these different tectonic plates of quasi-stable disciplines functioned, as being these trading zones, which could develop and form into their own disciplines. Or they could die out. Different things can happen. I began to study those, and that idea has been taken up by urban planners, and more politically, ecologists and other people who are interested in what happens when a soil scientist speaks to a farmer, or when regulators speak to fishermen.

One study is there’s a business community in an Italian city, the mafia, and the government. They’re trying to decide what happens in a group of blocks there. They don’t agree on foundations. They agree on how to go forward with pieces. It’s not a foundational picture. I’ve been interacting with a lot of the urban planners and people interested in ecology and other sort of real-world problems. Like what happens to the Everglades. What happens when Native Americans, the sugar plantations, the government, and so on, begin to try to figure out how water usage is going to work. Well, they’re not going to agree on what the foundational principles are—the conservationists are not going to agree with the Native Americans, are not going to agree with the government regulators, are not going to agree with the sugar plantations—but they can agree about water flows in certain limited cases. I’m interested in that process of a non-foundational picture of what happens at the boundaries of things.

How do you negotiate methodology between the tectonic plates, particularly history of science and physics? I would add film practice to that, because as you say it’s instrumentalized and not a transmittance of knowledge to a viewer. Is this back to the future? There’s a strong return to multihyphenated knowledge and cultural production—Da Vinci in the 1500s and Poincaré in the 1900s. Do you attribute this to material conditions, the deterioration of traditional career paths, lack of a safe place to hang one’s hat for an entire life, or do you take the view that in fact this is how knowledge evolves?

I do think it’s how knowledge evolves, but it doesn’t evolve in a nice, neat progression. My own view is that the Cold War—if you pardon my extension of the metaphor—froze the disciplinary structure for half a century. If you look at the division of disciplines—the disciplinary map—that someone would have drawn in 1948, it was different because of what had happened in the war from 1930. But it’s not that different from 1958, 1968, 1978, 1988. We have a recognizable structure of physics, chemistry, biology, philosophy, history, English, right? We have a sort of block structure of the way a university functioned, and the human sciences and anthropology and sociology and economics. We have a picture of how knowledge is partitioned, which isn’t to say there are never any interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary themes there. There are places you could find where that happened. But more or less, it stayed fairly stable.

At the end of the Cold War that stabilization began to break down. The world didn’t exhibit quite the same stability that it had during the Cold War. When we think of the Cold War we think it was a horror, we lived on the edge of nuclear brinksmanship and even apocalypse. But there is something reassuring about this mirror world—a bipolar world—and you knew where you stood. You could be aligned with one of the two or you could try to carve out some kind of status between them. But it was always against these two magnetic poles. At the end of that, suddenly people began to feel rather differently about the permanency of the structure of things. Nations that had been held together, like Yugoslavia, began to fall apart. Other alliances began to shift and change. Lots of things began to alter. The disciplinary structures seemed to reflect that change in the phenomenology of living in a world where every magnetic filing isn’t given an orientation by the two poles of the magnet.

But some would say that the departmental structure of academia have actually been far slower to change than one would imagine. You’re an interesting person to pose this question to because your work is very explicitly at the liminal point. When I posed this question to my dissertation adviser, I said disciplines as we know it won’t exist in the same way in 50 years. He said try 10. So the point being that it’s a domain where you don’t see people talking across the structure in a truly explicit way.

It’s a little bit like the pilot that arrived over Washington in 2001 and said, “Where are the cruise missiles?” In a sense we’re still in a kind of inertial state sometimes. But it is changing. There are places where you can see it. There are places where it’s been very hard! In my small-scale experiments in trying to do things that are differently configured I’ve had the experience very directly of having the big grant agencies say, “How could film be other than a question of dissemination and popularization? That’s what it’s for.” Or having conversely the academic side say, “Since film is just about popularization, it is a priori not scholarship.” I’ve four or five times been in the position of trying to persuade the documentary film community that things could have a scholarly value without being pedantic, expositional—and persuading the scholarly community that film can be other than popularization, or what the Europeans call vulgarization. It’s not what the British call a “popular understanding of science.” I mean, that’s fine. I have nothing against the popular understanding of science! It’s not what I want to do. I’m not interested in making a film called “The Race to the Double Helix,” or the “Triumph of Nanotechnology.” That’s just not the kind of film I want to make.

Film seems like a good place—to me, and I don’t say this prescriptively, there are lots of kinds of films and I don’t think everyone should do it like this at all—in finding places where understanding the tactile, the material, and the scale of things. It is something that the visual can often add to the textual. What does nuclear waste look like? What is it like to be inside a nuclear weapons factory or 1,000 feet underground in a salt mine where this stuff is being placed, or in an abandoned city in Nanae in Fukushima Prefecture? To use the visual as a way of conveying an understanding that isn’t purely captured in text. But it’s not because I think text is not valuable. They complement each other. There are some things that text does better and there are some things that images do better. The combination can do very interesting things. That’s one experience.

Can you speak to your collaborations with William Kentridge, Lorraine Daston, Mike Einziger [from Incubus], and others? On some level is collaboration—especially with people whose orientation toward the world is, at least superficially, different—crucial to your practice?

I do see it as crucial. One of the greatest pleasures and honors for me of the work that I’ve done is the opportunity to work with these people. It’s been productive and also very fun. I really enjoy it.

For instance, a mutual friend—David Edwards who teaches at the engineering school at Harvard—introduced Kentridge and me. Very soon we understood there was something we were both really interested in, and that was the way in the early part of the 20th century there was a kind of exposed modernism. Technology wore its function on its sleeve so to speak. You would build a motor or mechanism that could do very modern things, but you could see how it worked. It was like a car before it was blackboxed and built into printed circuits and controlling the flow of air and gas into the pistons. Everything was visible. We both found that just entrancing. We began our conversation. I had seen Kentridge’s exhibit at the Modern and he read Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps. So we began to meet and talk. He said to me, “I don’t want to do an artistic illustration of a scientific lecture. This isn’t an illustrated explanation.” And I said, “I don’t want to be a scientific adviser to an art project to give it, like in Hollywood, scientific authenticity, to give it a feel of ‘What do cops really say when they get to a crime scene?’”

I didn’t want to “What does a scientist really do when they pick up a test tube.” That’s of no interest to me at all. I’m happy for other people that do it if they want, but I don’t want to do it! We got that out of the way and we began to talk about this moment at the beginning of the 20th century and doing something around the theme of time. We were both interested in materiality, in this way that physical and visual things could elicit thoughts about big issues like mortality and fate. Time is interesting as a physical concept because it’s woven deep into the history of physics. It’s really fundamental to the way that physics has developed. Newton thought that the idea of absolute thought was one of the central and most important concepts when he wrote the [Philosophiæ Naturalis] Principia Mathematica, his masterwork in the 17th century. Einstein thought it was the key concept to relativity. Each generation of physics re-engages with this—quantum mechanics did. What happens to information near black holes is a current issue of urgent concern to string theorists.

Time is always both part of science and something other than science, in a way that other concepts might not be. I mean, angular momentum is very important in physics but poets don’t write about angular momentum on the whole. Whereas changes in the idea of time elicited responses from every major Modernist poet in the years after 1919 when Einstein became a world figure: e. e. cummings, William Carlos Williams, I mean, everybody! There’s a way in which we thought we could use time. The collaborations have been very productive for me and they often begin with a concern where I see that I want to get at something, and understanding the problem isn’t going to be possible entirely within the boundaries of what I ordinarily do.

But you’re also an unusual practitioner of film, not because you’re a historian of science but because you’re connected to the idea of materiality and image and yet your primary areas of concern are things like time, secrecy, waste—things we don’t typically associate with materiality or image. I’m imagining what challenges you encounter when you approach setting up a scene around time, secrecy, or waste.

One of the things—say, with Kentridge—that I found funny as a kind of philosophical joke is there’s a point in the 19th century when they pumped a time signal in pipes underneath Paris. This idea that time could be pumped just seemed to me incredibly funny. When I told Kentridge about this and showed him pictures of the machines that pumped time, he also liked that. That was one of the places that we began to talk about setting up machines and this pneumatic time could actually be something very interesting. I liked it originally because it was a way of materializing something abstract—that it was materialized. That’s how people reset clocks in every arrondissement in Paris, for example, or Vienna. You had a clock that was set to a pump that was set to the observatory and it pumped this sudden blast of air through the pipes and it reset the clocks. That’s a place we could begin to think, How can we use this? How can we riff of this more than metaphor? Each of the three stages of the Kentridge collaboration—the idea of coordinated clocks, the relativistic time, and then the black hole time—became the structure for Refusal of Time.

I remember hearing you say how smoke during Einstein’s time was seen as an artifact of modernity, a material of great contemporary importance. What your work illustrates is that our current moment does that too. And you’re simultaneously de-archiving the idea of the modern by saying, “Hey, they used to pump time in Paris.”

Just along those lines, I like ideas that are, like time and secrecy, both literal and metaphoric at the same moment. That really intrigues me—it’s central to an idea of humor and it gets deep at something. I think of it in a way as both philosophically and scientifically but also politically to reliteralize our concepts. To regain what can pass into pure abstraction into the referential materiality of our world. And to think about: what are secrets? How are they actually transmitted? That article you read—“Removing Knowledge”—is one of a series of pieces that I’ve done about the question, How does it actually work? How is it removed? How do you distribute it? There’s an original classifier. And the derivative classifiers. And here are their rules of operation. The theory that lies behind the question, How do they actually make things secret? That’s interesting to me.

The same with time. How do you actually go about telling time? The centerpiece of the Einstein, Poincaré book is about this moment—which I consider to be one of the decisive moments in the whole history of science—where Einstein says, The problem is what does it mean to coordinate clocks? What does it actually mean? How do you actually go about doing that? Or with waste: what does waste look like? What does it do in these million-gallon tanks, 177 of them in Hanford and 51 of them in Savannah River Site filled with this stuff. It’s got the consistency of peanut butter, it’s leaking out, some of it is boiling with these big hydrogen burps. It’s leaking into the ground. It’s gotten into the Columbia River. It matters that you understand that waste isn’t an abstraction. That there’s stuff.

And once you begin to see it in its literal form it also immediately takes you into a metaphorical and metaphysical domain. If it lies in a kind of midrange, we don’t hear it. It’s like we’re a strange kind of creature that can understand real metaphysical or physical abstraction, and we understand materiality, but when you leave things like, “Oh yeah well, there are a lot of secrets.” Well, yeah, there’s a lot of nuclear waste, and where is it stored? “Oh, it’s stored somewhere.” It doesn’t mean anything. That’s not real abstraction. That’s just hiding out from what it is.

So if you want to act, if you want to understand this, you need to understand it in its material, quantitative, geo-located form. Then you can begin both to associate what it is and you can understand it. But you can also riff off it and understand how it signifies to us in a metaphorical and often political way. For instance, in the beginning of my work on secrecy I thought it’d be very interesting to tie practical, national security secrecy to personal, Biblical, sexual secrecy. Wouldn’t that be interesting, if people saw some connection—but I had no idea whether they would or not. One of the things that surprised in making the film with Robb—I did most of the interviews, and when I’d be talking to one of the people—without exception, anybody, people who wanted to expose secrets, reporters from the Washington Post and New York Times, ordinary citizens, people caught up in it, the people with the National Security Agency, CIA interrogators, everyone saw an immediate connection between the more personal, abstract notions of secrecy and concrete national security secrecy. The film—I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to see the film—

Of course.

It starts out with this very senior fellow from the National Security Agency who believes very strongly that protecting secrets is necessary for our national security. He’s a tough, pragmatic guy. The film starts by him saying, “Secrecy is like forbidden fruit. You can’t have it. It makes you want it more.” The idea that you’re back at the Garden of Eden, and desire, at the same moment that you’re talking about the National Security Agency was characteristic of everybody we talked to. I thought that was extremely interesting.

The same with the nuclear waste and the same with the work on time. You talk about time and you already always talk about mortality. Time and finitude and death and the fragility for all things—it’s there all the time. We might change our ideas of time from medieval painting that includes an hourglass in it, or debates between Hawking and others in contemporary string theory. But you’re always talking about something more than that.

There’s a moment in a film that Errol Morris did—A Brief History of Time—where one of the young physicists that worked with Hawking did a calculation and Hawking said that time will cycle around. It’ll come around and things will recur. The physicist did this calculation and said, “No Stephen, it doesn’t do that. It doesn’t go back.” Hawking says, “Do the calculation again.” And as this young physicist tells this story about this insistence that Hawking said there must be another round of time you suddenly realize that Hawking is talking about his own mortality, his struggle with his devastating illness, with the hope for renewal, even if it’s a cosmic renewal that’s not going to help him personally. There’s a way in which time is never just about time. It’s not like angular momentum: you may not have a view about angular momentum. But you have a view about time.

I often begin a first meeting of a course by asking students to read Hegel’s short essay, “Who Thinks Abstractly?” (1808). He deftly argues against the commonsensical notion that it is the philosopher and not the “common populace” who thinks abstractly. He gives attention and weight to concrete reality as a deterrent against a pure universal. I’m reminded of it in the way you light a match to theory through concrete materiality.

When someone asks me something abstractly, I’m often asking, “What concrete situation do you have in mind behind your abstraction?” Because most of the time when we talk about something abstract we have in mind something, an incident, an autobiographical event, a political occasion, a physical object. I’m constantly trying to understand in a debate or an argument, whether it’s political or philosophical, what’s the concreteness that’s lying there behind the verbiage of abstraction? Conversely when I look at concrete things—not everything, but some things—are particularly allusive to another world. That’s why I’ve chosen these topics like time, waste, secrecy, and so on. They allude elsewhere, and it’s the sudden juxtaposition of the very concrete and the very abstract that is to me so engaging.

I did a piece on Freud and censorship. What interested me was the way the real techniques of censorship in Freud shaped Freud’s understanding of the structure of the mind. Freud’s understanding of the structure of the mind gave him an understanding of how the political censorship worked. He tacked back and forth between them. It’s not an accident that the articulation of censorship took the form that it did, and his more topographic concept of mind that developed in World War I. It’s a concrete practice but it’s one that alludes elsewhere.

The idea that when Einstein talks about trains, stations, and clocks that he might actually be talking about trains and stations and clocks is very funny to me. We lost that—and that’s why I wrote that book. It had become like when philosophers talk about a brain in a vat. Imagine you’re a trolley driver and you’re driving down the road and you can choose the left fork and the right fork and there are two grandmothers on the left and three kids on the right. It just seems like low-level—I wouldn’t even privilege it by calling it science fiction—but it’s kind of a vulgarized sense of science fiction. But that’s not what Einstein was doing. There were real clocks and real trains and Poincaré was really in charge of synchronizing clocks across the globe to make real maps that were used in the distribution of goods. And it was also physical and philosophical: that triple conjunction of the physical, the technological, and the abstract.

We met at the Boston marathon—thought to be a default “safe” space in public. I was running toward the chaos from the outside to find my students. You were running toward it from the inside. We met on the subway when I noticed you wearing a GALISON runner’s badge. You were shaking, traumatized, and wrapped in aluminum. It was very different than the “towering scientist” image of you.

I’ve always wanted to have something that wasn’t academic or personal. Something that would engage me with a community—something physical and outside. I used to fly little airplanes in California when I was teaching at Stanford, and from here too. At a certain point I decided I didn’t have the time, and it’s not the safest thing in the world to do. I had two small children, and it wouldn’t be so great if I crashed. I decided to do something different and I started running more intensively, thinking, That’s a good safe, on-the-ground thing to do!

I worked very hard to prepare for this marathon and I joined a charity team and worked with a very nice coach. It’s such a cheerful community of people I wouldn’t ordinarily be in contact with, as the flying was too. Running was a big deal for me, and my father used to run marathons. I thought it was a nice thing that way too. Then this event came. It was thrilling for me. It was so fun to be out with all these thousands of people. Everyone’s cheerful and anticipating it. My family was waiting for me at the finish line. I was excited about getting there. To come right up to it and then—it was sort of uninterpretable. You’re tired—I’d never run that far in my life, I’d practiced up to 20 miles but never run 26.

Just at the end, suddenly I come to a barrier. It seemed irrational. I couldn’t even think straight. And they said, “There have been some explosions at the finish line.” I just couldn’t absorb it. Then when I realized what they were saying was true I hustled over to try to get to where my family was. I didn’t know if they were safe, I borrowed people’s cell phones but couldn’t get through. Finally I found out from my son who lives in New York that he’d heard from them and they were all OK. I didn’t have my little Mylar blanket so I was completely freezing. When you run you become 20 degrees warmer than you are normally, so if it’s 50 it feels like 70. But the other way is true too. When you finish running suddenly you lose 20 degrees. So I was really shaking with cold.

Finally when I met you I had found somebody on the corner who was distributing these Mylar blankets. But it was totally broken: nothing was working. No one knew anything. You probably saw these giant trucks that said things like MASS DECONTAMINATION. I mean, weird kind of dreamscape things, objects that I’d never seen before. Trucks with soldiers in camouflage. I couldn’t get to my family, things were blocked off. I thought I’d hitch up Storrow Drive, but the police wouldn’t let me in there. I walked to the Charles Street Station. I met you on the train back to Cambridge. It was such a shock. Gradually your reality begins to reconstruct after a traumatic event and you begin to find a certain normalcy. Even then the train we were in was stopped because of another bomb scare in Harvard Square, so the train stopped at Central Square, which they didn’t tell us but that’s why it stopped. It was just wild.

There was a moment of complete destabilization where suddenly this very festive event became a traumatic one. That sound of ambulance after ambulance after ambulance—you probably heard that, right?—dozens and dozens of ambulances. Trying to interpret what was happening and partial information. And then this lockdown! I finally got sick of being in the house and there’s this helicopter [makes whooshing sound]—I live fairly near the Watertown side of Cambridge—and the fragility of our everyday lives was brought very much into focus. People who live in conflict zones face that all the time, but we don’t here. Suddenly it was very present and very sad. I felt very bad for the people who had been so wounded.