In The Attention Merchants, Tim Wu makes this claim about channel surfing:

When you think of it, channel surfing, or grazing, is a bizarre way to spend your time and attention. It is hard to imagine someone saying to himself, “i think I’ll watch TV for three hours, divided into five-to-ten-minute segments of various shows, never really getting to the end of anything.” It hardly seems the kind of control Zenith could have had in mind when it first introduced the remote, to say nothing of the sovereign choice that cable’s more optimistic backers had dreamed of. However fragmented, attention was still being harvested to be sure, but the captivity was not a pleasant experience.

It seems strange to me that Wu assumes that people automatically experience fragmentation as unpleasant. Dividing up one’s attention into smaller and smaller bits is a mode of mastery; it’s precisely the sort of control that remotes afford. And who always wants to get to the end of anything? The end is ultimately death. But while you are channel surfing you never need to die. The remote becomes a panegyric that lets you feel like you will live forever, as long as you can keep clicking.

Wu seems to assume that there is some already integrated self that precedes an encounter with media, and that the media then has the effect of tragically destroying that whole, breaking us apart, undoing our dominion, our "sovereign choice." But sovereignty when consuming media (or anything else) is not in making one choice and being done with it, in being satisfied by it. Sovereignty lies in the ability to keep choosing, to experience the proliferation of options and know you will never reach the final decision.

Those choices don't reflect some pre-existing preferences but permit a self to take shape. Consuming media can consolidate one’s attention into a single focus, but where you focus makes you into someone else, something specific, dictated by the nature of the content being consumed. Fragmented attention represents the multiplicity of what we are, or at least can always potentially be.

Wu assumes everywhere in The Attention Merchants that people are only in control when they are unwaveringly glued to something, when their attention is consolidated and chained to a single object. He depicts advertisers as usurping individuals’ executive functions by tapping into their “lizard brains” and forcing them to attend to presumably primitive, atavistic things. This, in his implicit view, steals their selfhood away and reverts them to an animal-like state of instinctive reactivity. The solution then would be to pass laws that essentially bind us to the mast so we can’t be lured by the sirens — laws that in effect would force us to be who we “really” are, and not the lizard inside us.

But it may be that distractibility isn't the way we are controlled, and the "lizard brain" is not some subhuman subcognitive function that threatens to control us but a higher functioning, the means by which we escape threats and disrupt otherwise endless behavioral loops.

Something that is great at consolidating executive function, as Natasha Dow Schüll details at length in Addiction by Design, is a video-gambling machine. People are so focused by these machines that they can’t bring themselves to go to the bathroom while playing for 18 hours at a stretch. It is "sovereign choice" at its purest. But that can’t be the sort of self-control Wu is advocating.

Sometimes it feels good to have our attention led, sometimes it feels good to think we are deploying it. But attention never sits idle in our consciousness, waiting to be assigned. It is not a resource that can be hoarded or spent unwisely. It can only be convened.

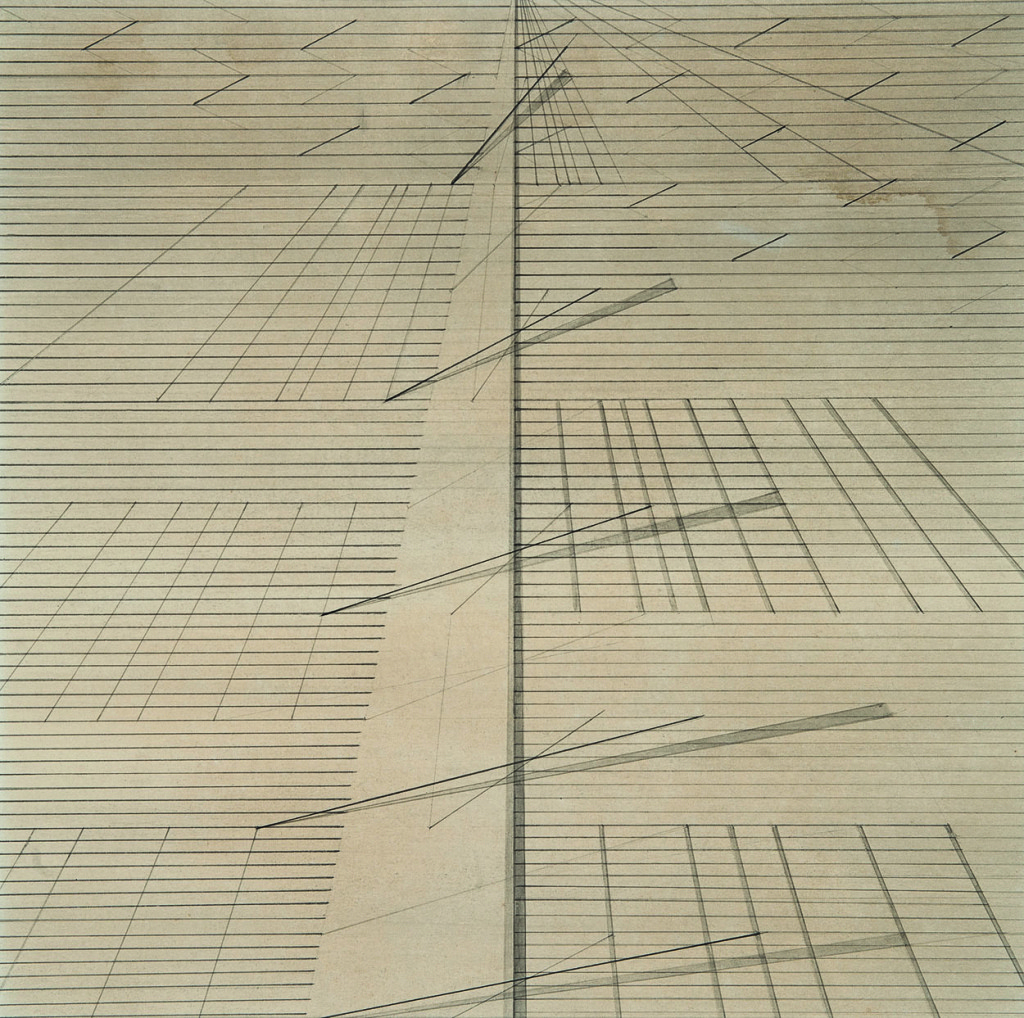

It may be that attention should not be thought of as “fragmented” or “focused” as if these were opposites; fragmentation can look like focus, focus can be serially distributed on fragments. Fragmented focus and focused fragmentation.

Operating a remote control, or a phone, or a gambling machine is using an interface to delimit overwhelming possibility; we bring it down to size by fragmenting it, subjecting it to a process. The process — clicking buttons, exercising clear choices, or setting up a series of choices for ourselves that center us as the chooser and guarantee we will have somewhere to place our subjectivity, which is always leaking out and slipping away — makes our attention seem like something projected out from our pre-existing consciousness, rather than a matter of our mind catching up to what is happening to us. These interfaces makes attention seem to precede focus, when attention may be the product of being forced to focus by stimuli. In other words, we don't have attention to spend, rather we have experiences that produce a sense that an "I" exists that can attend on things.

But it may be that both of these perspectives are illusions that can always be inverted into each other, like Gestalt images of an hourglass that is also two faces.

Why does any of this matter? Because making the claim that advertisers, et al., are hijacking our attention is a way of positing a particular kind of economistic self, one that has and spends attention in a marketplace of ideas. It then follows that the state apparatus should be deployed to make that "market" function more fairly. But this misconstrues ideas and experiences as commodities that attention purchases, which is an extremely narrow frame through which to view life.

In the "Postscript on the Societies of Control" Deleuze argued that institutions (and the way they conditioned subjectivity through discipline, rules, and closed environments) were being supplanted by a new form of control oriented around permission rather than obedient rule-following. Interfaces like remote controls are manifestations of the "society of control" and its "limitless postponements"; choosing from among the options on TV subjects one to more reliable control than forcing people to watch the same thing and trusting the power of whatever propaganda message is encoded there. That is, the illusion of spending attention is a form of control that operates at the level of media form rather than media content. The ability to flip between channels is what indoctrinates us, not the content of any one channel.

Wu seems to think that watching one channel at a time would address that danger, but that is moving backward; that is nostalgia for disciplinary societies, as if they could fix control societies (rather than be a more overt and oppressive form of control). He wants content to be sovereign again, for a particular message to be capable of controlling us, and for us to interpret our ability to focus on that message as an expression of our sovereignty: "It held my attention" becomes "I paid attention" because the content seems important, comprehensible, convincing, coherent, assented to.

But no particular content seems strong enough. It has all become interchangeable, because its function now is to keep us clicking.