By Cassia Roth

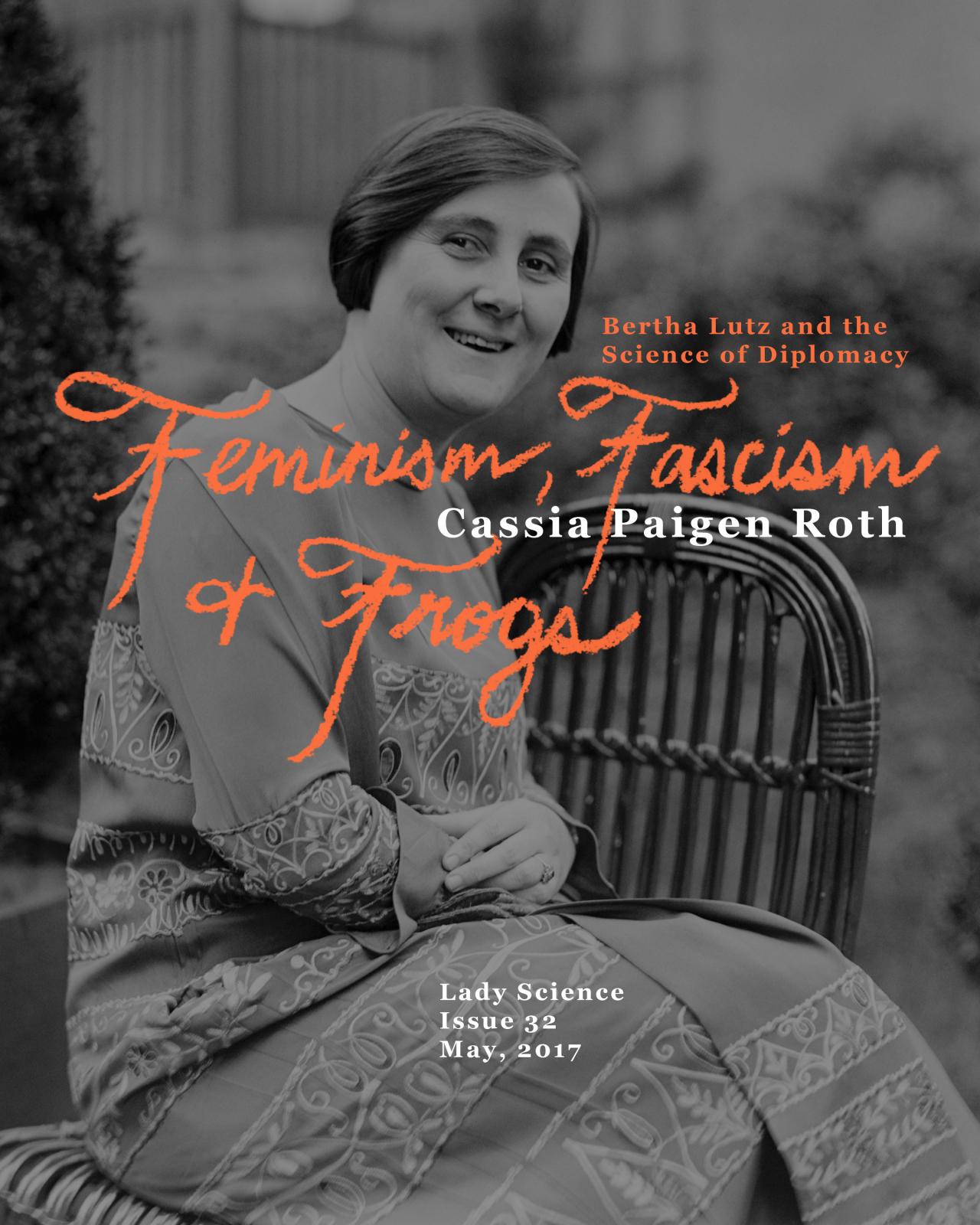

In the summer of 1945, the Brazilian scientist and suffragist Bertha Lutz arrived in San Francisco to participate as a delegate at the United Nation’s founding conference. At first glance, Lutz’s presence at the conference seems a logical step in her impressive feminist career. Lutz had been at the forefront of Brazil’s suffrage movement for decades as president of the Federação Brasileira pelo Progresso Feminino (Brazilian Federation for Feminine Progress, FBPF). After Brazilian women achieved the vote in 1932, Lutz became one of the first women elected to Congress.

Lutz was also a leading figure of the international feminist scene in the interwar years, participating in numerous global conferences on suffrage and women’s rights, and closely allying herself with Carrie Chapman Catt’s U.S. National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Her feminist organizing in the 1920s and 30s was matched only by her dedication to her scientific career. Trained as a zoologist and working as a herpetologist (the study of frogs), Lutz gained international prominence in the 1930s, a period when prominent female careers in science were rare in Brazil—and across the globe.

Lutz’s feminist and scientific agenda were intricately interconnected. When Lutz wrote Thirteen Principles in 1933—a feminist guide for the committee that was rewriting the Brazilian Constitution—she included specific mentions of women’s intellectual equality to men and used rational scientific language. Additionally, the FBPF supported and attended scientific events such as the 1934 First Brazilian Conference on the Protection of the Environment. Historians have contended that “[Lutz’s] involvement with the scientific environment influenced and found support in this group of women [the FBPF] who sought to occupy more and more public spaces and participate in important decision-making processes for the society in which they lived.” When Lutz became a member of Congress in 1936 and assumed the chair of the Special Congressional Commission on the Statute on Women, she put forth both a scientific agenda and feminist one. Her personal correspondence with feminists, government officials, and scientists includes references to both her feminist endeavors and her scientific career.

Lutz’s longstanding and illustrious feminist activism and her adherence to transnational organization seems to be the obvious reason behind her presence at the UN in 1945. But if we look more closely at Brazilian politics at the end of World War II, her role at the conference becomes more complicated. In fact, her presumably neutral scientific career was also a key factor in her UN participation.

Throughout the 1930s, Brazilian politics became increasingly populist under the leadership of president Getúlio Vargas. His rise to power in 1930 altered the existing political structure based on a tradition of patronage and economic privilege. As we saw, this political change initially facilitated the continued efforts of the FBPF, as Vargas was sympathetic to their cause. But the progressive legislation of the early 1930s that Lutz and her fellow feminists had fought for was short lived. By the mid 1930s, political unrest threatened the government, which began to crack down on political organizing.

In 1937, Vargas dissolved Congress and ended electoral politics with the onset of his fascist dictatorship, the Estado Novo (or New State, which lasted until 1945). The Estado Novo co-opted all forms of activism, subsuming labor and women’s rights under a clientelistic patronage system in which the government provided services and favors in return for support. The Estado Novo de-politicized the women’s movement by including it within an authoritarian political system. Vargas’s new regime was both inherently and explicitly patriarchal and paternalistic. He rhetorically fashioned himself as the “father” of the nation, and his political ideology relegated women to the roles of wives and mothers. Vargas’s actual policies, including protectionist legislation that discriminated against working women, put this rhetoric into action. Of course, fascism functions in funny ways. While Vargas was cracking down on democratic policies at home, he was also the only Latin American leader to join the Allied forces fighting in WWII.

Lutz’s role in creating the UN’s framework in 1945 to prevent the return of international fascism marked almost a decade since Brazilians had been able to participate in democratic politics at home. And Vargas, who had sent her to San Francisco, was still intent on promoting dictatorship. Katherine Marino has demonstrated how Lutz’s continued pan-American feminist organizing throughout World War II and the Estado Novo kept her at the forefront of international feminist issues—if not national ones. Clearly, Lutz still had considerable standing among both the leaders of the Brazilian feminist movement and those of their international counterparts. But why did Vargas, who was ruling as a fascist at home, send a strident feminist to represent Brazil at the UN?

Lutz’s scientific career during the politically repressive Estado Novo gives us insight into her participation at the UN. With the Estado Novo, Vargas had created a strong federal government that supported the arts and sciences through wide-reaching and well-funded initiatives. In fact, Vargas viewed the development of national culture—art, scientific inquiry, education—as central to his creation of a nationalistic Brazilian identity. Fascists aren’t inimical to cultural and scientific pursuits. On the contrary, state support for scientific inquiry has long been the lynchpin of fascist regimes the world over. So while Vargas shut down Lutz’s political ambitions after the Estado Novo, his extensive state patronage for science as a “Brazilian” pursuit opened up a politically neutral public space for Lutz’s scientific career to flourish.

Lutz’s scientific career thrived during the dictatorship and she rose in the ranks as a tenured faculty member at Rio de Janeiro’s prestigious Museu Nacional (National Museum). Lutz had entered the Museum as a secretary in 1919, only the second woman to hold a position in the civil service. In 1930, she was promoted to secretary of translation and in 1937, Vargas promoted her to the position of naturalist, with successive promotions in scientific rank throughout the Estado Novo. In 1939, Vargas named Lutz to the Brazilian Inspections Council on Artistic and Scientific Expeditions (CFEACB), where she became an important and decisive member until 1951. She took over the position from her friend and colleague Heloísa Alberto Torres, daughter of the famed abolitionist Alberto Torres, who had left to become the first female director of the National Museum.

While at the CFEACB, Lutz worked with other leading scientists and intellectuals to formulate policy on diverse matters including the development of the sciences and the protection of the environment. Lutz’s work in the CFEACB demonstrated her interest in supporting the growth of scientific institutions in Brazil and connecting those institutions to larger political goals. She also became active in museum studies, participating in international conferences and publishing on the subject in Brazil. Her scientific organizing placed her in a less-than radical public position, one which feminists seized upon when they began lobbying Vargas to include a woman delegate to the UN.

At the UN Conference, Lutz proved instrumental in changing the Charter’s language and in creating the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW). In 1948, she, along with Virginia Gildersleeves of the U.S., Minerva Bernardino of the Dominican Republic, and Wu Yi-Tang of China, were the only women to sign the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights. As UN historian Hilkka Pietilä writes, “[These women] were instrumental in the movement that demanded the Preamble to the UN Charter reaffirm not only nations’ ‘faith in fundamental human rights’ and ‘the dignity and worth of the human person,’ but in ‘the equal rights of men and women.’”

Only months after Lutz’s return to Brazil, Vargas was deposed in a coup. In a November 2, 1945 letter to her brother Gualter, Lutz flipped the gendered script of the Estado Novo when expressing her views on the coup: “one can’t help feeling a bit sorry for him. At the last every one of his creatures abandoned him.”[1] The country’s patriarch had fallen and needed taking care of. Perhaps Lutz felt endearment to the man who had helped win the vote for women (before taking it away) and who had sent her to the UN.

Whatever her feelings for Vargas, Lutz’s actions at the UN in favor of international democracy surely influenced politics back in Brazil. When Lutz’s feminist ambitions to advance women’s political participation faltered at home, her efforts to promote gender equality in science flourished. And this dedication to science allowed Lutz to return to international feminist activism, where her participation in the creation of an international democratic framework perhaps weakened fascist rule in Brazil. Both frogs and feminism helped Bertha Lutz defy fascism at home and abroad.

- Museu Nacional, coleção Bertha Lutz, correspondência, document 115/9.

Further Reading:

Susan K. Besse, Restructuring Patriarchy: The Modernization of Gender Inequality in Brazil, 1914-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

Katherine M. Marino, “Transnational Pan-American Feminism: The Friendship of Bertha Lutz and Mary Wilhelmine Williams, 1926-1944,” Journal of Women’s History 26, no. 2 (2014): 63-87.

Cassia holds a PhD in Latin American history with a concentration in Gender Studies from UCLA. Beginning fall 2017, she will be a Marie Curie Sklodowska Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. Her research examines the history of reproductive health in relation to legal and medical policy in turn-of-the-century Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She is a contributing writer at Nursing Clio. Follow her on Twitter.