Soon the whole bridge was trembling and resounding. The uncouth faces passed him two by two, stained yellow or red or livid by the sea, and as he strove to look at them with ease and indifference, a faint stain of personal shame and commiseration rose to his own face. Angry with himself he tried to hide his face from their eyes by gazing down sideways into the shallow swirling water under the bridge but he still saw a reflection therein of their topheavy silk hats, and humble tapelike collars and loosely hanging clerical clothes... Their piety would be like their names, like their faces, like their clothes.

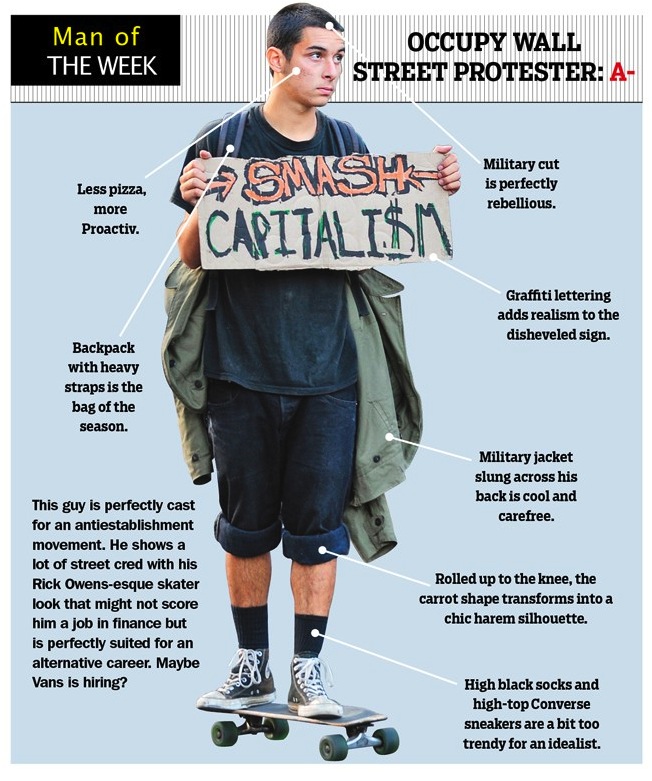

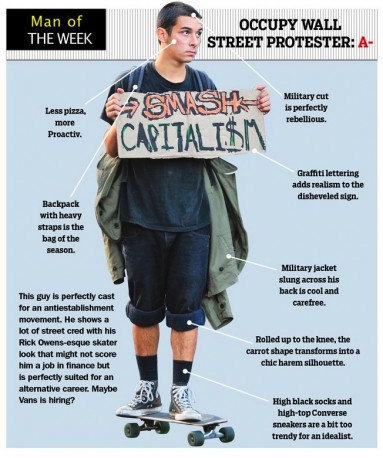

11. Women's Wear Daily picked an Occupy Wall Street demonstrator for their 'Man of the Week’ spread, ranking each personal clothing (and even bodily) feature in a tight sartorial classification system. They conferred high marks on him due to a bizarre fixation with verisimilitude ('perfectly cast for an antiestablishment movement,' 'graffiti lettering adds realism to the disheveled sign,' 'Converse sneakers are a bit too trendy for an idealist').

11. Women's Wear Daily picked an Occupy Wall Street demonstrator for their 'Man of the Week’ spread, ranking each personal clothing (and even bodily) feature in a tight sartorial classification system. They conferred high marks on him due to a bizarre fixation with verisimilitude ('perfectly cast for an antiestablishment movement,' 'graffiti lettering adds realism to the disheveled sign,' 'Converse sneakers are a bit too trendy for an idealist').

? ? ?

12. 'Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life. I don't think you could do away with it—it would be like doing away with civilization.' Bill Cunningham New York, the documentary film which takes New York's most uncompromising and least corrupted figure in fashion as its subject, featured the trailblazing octogenarian whose sensitivity for beauty mutes the doctrinal power drive of the dominant fashion industry. We learn that Cunningham left his job at Women's Wear Daily decades ago after being horrified by their misuse of his photos to rank, humiliate, or pooh-pooh ordinary women who personalized their looks rather than adopted them straight off the runway (a tendency echoed in the photo inlet in the previous entry).

Director Richard Press and producer Philip Gefter revealed it took eight years to persuade Cunningham to allow a film to be made about him and two years to trail him. They ended up with over 100 hours of footage. Despite all this, Cunningham has never watched it (he is too busy and insufficiently self-involved). His importance to fashion journalism is compared to a deity: when his employers at The New York Times require a historical photo of the city in the past fifty years they consult Cunningham's files. Not only are they impeccably organized at his spartan bathroom-and-kitchen-less studio but he is the only person alive who retains them, having followed the clothing whims of ordinary people with an egalitarian tenacity unknown to the fashion industry ('The fashion show is on the street. Always has, always will be').

Cunningham works from eight in the morning to midnight, seven days a week. The film lays bare the fact that his dogged pursuit of contemporary sights are derived from a wild sense of curiosity and passion, upending commonsensical notions about 'personal branding.' His singular presence redefines what it means to respect one's craft in an industry often bent on destroying or manipulating it, or by churning 'dreams' into very low-wage labor. 'If you don't take money they can't tell you what to do. That's the key to the whole thing.' In the era of corporate exploitation, vast journalistic collusion with institutions, and professional mollycoddling, Cunningham manages to meticulously cover fashion while defying the industry itself, refusing to even eat a meal at an event he's covering for fear of being journalistically compromised.

? ? ?

13. Two stories about young people and their spending (or lack thereof) emerged within days of each other in October 2011. In The New York Times, 'The Campus as Runway' profiled the clothing choices of Columbia University students. At The Washington Post's 'Campus Overload' Jenna Johnson blogged about how massive student loans—the kind that leave young people with little to no disposable money for even modest purchases, unless they plunge into spending debt—played a defining role in Occupy Wall Street.

? ? ?

14. Barneys New York creative director Simon Doonan (who lives in a 2,500-square-foot apartment duplex in Greenwich Village) wrote 'The Fashion of Occupy Wall Street,' roundly attracting invective for the blasé attitude to the politics and the idiosyncratic amusement for the clothes.

Sporting peace signs and granny glasses, these vintage Lefties are often to be found 'teaching' barely audible lessons to small groups of pale-but-riveted young activist-ettes. While the hippie sages favor traditional Woodstockian attire, their acolytes are wearing nouveau grunge—checked shirts and skinny jeans—from Urban Outfitters and the like.

Doonan refused any probing or questioning beyond a strictly superficial reading of what people have on. On men wearing banking and executive apparel:

Are they CIA infiltrators? Have they lost their jobs? Have they lost their minds? It was impossible to tell. Either way, they look extremely spiffy in their custom suits.

? ? ?

15. Following the takeover of the Brooklyn Bridge the Chelsea-based PR firm Workhouse Publicity, which has represented Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Fifth Avenue, blasted out an unsolicited email (subject: 'Occupy Wall Street: News from the Front,' tagline: 'The Revolution Will Not be Editorialized') to its listserv. After being prodded to comment by the press, the company released a statement—it is unclear whether it was written by the CEO Adam Nelson or empathetic PR workers—that referenced the demonstrators' frustration with lack of media coverage as the marches began: 'We have no agenda and our service in this regard is simple: Publicize the message as the march continues.'

? ? ?

16. In October 2011 The New York Times published a 12-part slideshow called 'What to Wear to a Protest?' asking each participant (ranging in age from 19 to 68) to describe what they were wearing and why they were at Occupy Wall Street.

Judith Carluccio, 68, Retiree. 'My black velvet jacket is from J. Jill. My jeans, I’m not sure where they’re from. And I have on sneakers so I can run. In case the cops come, I’m ready to go.'

Nathan Torrence, 23, Instrument maker. 'We’re a band called Environmental Encroachment. The leggings, I like to provide some hallucinogenic visual stimulation for people. Pretty much everything I’m wearing is supposed to be awe-inspiring and hallucinogenic. And it also feels really good to wear tights.'

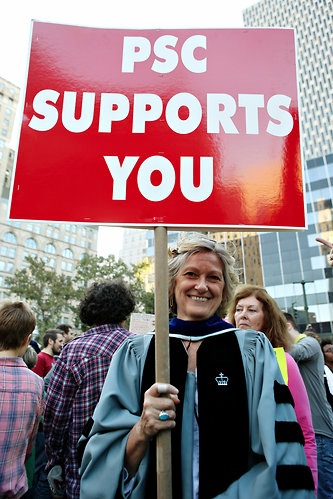

Mary Refling, 57, Italian professor at Bronx Community College. 'I’m wearing my Columbia robe because I got my Ph.D. from Columbia. If I wear my robe, they’ll get the idea it’s the faculty union.'

? ? ?

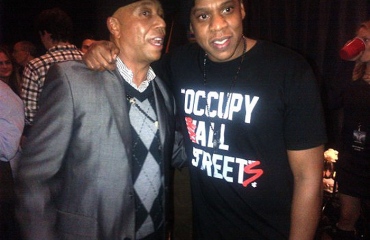

17. Rocawear founder and CEO Jay-Z (annual sales: $700 million) planned to sell 'Occupy' t-shirts for $22 each but the immediate backlash reversed that decision. A Rocawear spokesperson said, 'We have not made an official commitment to monetarily support the movement.'

An awkward moment wherein business tycoon Russell Simmons stood next to Kanye West at Zuccotti Park and spoke for him: 'Kanye has been a big supporter spiritually for this movement.'

18. A month prior to the beginning of Occupy West and Jay-Z had released their collaborative album Watch the Throne, laden with braggadocio about hyper-conspicuous consumption. Cord Jefferson negatively compared the album's self-professed social impact to the actual legacy of the Black Power movement it claimed to uphold:

Fred Hampton, who Jay-Z likes to intimate he was born to replace, ended up on the FBI's radar in the first place because he used to advocate for the destruction of capitalism. 'You don't fight fire with fire,' he once said in a not uncommon inveigh against America's preferred economic system. 'You fight fire with water.... We're not gonna fight capitalism with Black capitalism. We're gonna fight capitalism with socialism. Socialism is the people. If you're afraid of socialism, you're afraid of yourself.'

Yasiin Bey (formerly known as Mos Def) countered West and Jay-Z's 'N****s in Paris' with 'N****s in Poorest,' rapping 'Poor so hard / My clean clothes look grimy.' In response to Jay-Z's line about no longer being able to determine the value of $50,000, Bey slams, 'So what's 50 grand to a young n**** like me? / More than my annual salary.'

'Every society in history gets to choose what is powerful and revolutionary to it,' Jefferson argued, 'whether that be monarchs, clergy, armed socialists, or rich people. Many people in our generation, despite what Occupy Wall Street may have made you think, have chosen rich people. Jay-Z and West were simply there to take the money and rise, and then convince everyone that songs about buying Maybachs, watches, and lavish vacations are revolutionary acts.'

The anarchist rapper Testament responded to Jay-Z and West's video 'No Church in the Wild' (directed by Romain Gavras, whose images are associated with glamorized, context-less rebellion) with an indignant interventionist track called 'Run Kanye Out of Town' ('all-black everything Black Bloc masked up').

? ? ?

19. In a February 2012 article called 'The Cancer in Occupy' Chris Hedges wrote that 'Black Bloc anarchists' (especially those active in Oakland) were the 'cancer' of the Occupy mobilization, an argument that hinged almost entirely on a superficial matrix between people, tactics, and clothing.

The presence of Black Bloc anarchists—so named because they dress in black, obscure their faces, move as a unified mass, seek physical confrontations with police and destroy property—is a gift from heaven to the security and surveillance state.

Hedges did not make it clear how people who cover their faces to evade detection in what he himself called a surveillance state aided the phenomenon they attempted to escape. He linked his diagnosis of the 'Black Bloc anarchists' malaise directly to their apparel of choice, concluding their actions were motivated by a full appetite for rampant destruction.

Marching as a uniformed mass, all dressed in black to become part of an anonymous bloc, faces covered, temporarily overcomes alienation, feelings of inadequacy, powerlessness and loneliness. It imparts to those in the mob a sense of comradeship. It permits an inchoate rage to be unleashed on any target.

Hedges made emphatic comparisons between groups of people with a similar ideology (specifically: men in black) to the police, who accessorize with pepper spray and batons. Ignoring the forces that crushed Occupy encampments in every city they sprang up, he moved beyond the 'cancer' analogy to essentially call them animals.

Pity, compassion and tenderness are banished for the intoxication of power... It is the sickness of soldiers in war. It turns human beings into beasts.

In 'Concerning the Violent Peace-Police' David Graeber discussed the nature of the tactic in contrast to Hedges' inflamed demonization:

Black Bloc is a tactic, not a group. It is a tactic where activists don masks and black clothing (originally leather jackets in Germany, later, hoodies in America), as a gesture of anonymity, solidarity, and to indicate to others that they are prepared, if the situation calls for it, for militant action. The very nature of the tactic belies the accusation that they are trying to hijack a movement and endanger others. One of the ideas of having a Black Bloc is that everyone who comes to a protest should know where the people likely to engage in militant action are, and thus easily be able to avoid it if that’s what they wish to do.

Other groups (in this case predominantly or totally male, unlike the many women involved in the bloc as a tactic) who dress alike and seemingly carry the same ideology escaped Hedges' rhetoric of disease and bestiality: clergy and Veterans for Peace.

? ? ?

20. In the wake of Occupy New York reinforced an anti-mask law on the books since 1845. The statute prohibits individuals in groups of three or more from masking their faces. First enacted in 1845, in response to Hudson Valley tenant farmers who rebelled against their indebtedness to landowners in the guise of Native Americans, the legislation was reenacted in its current form in 1965. The state used the law, which is not beholden to federal, constitutionally protected free speech laws, to prosecute individuals at the 2004 Republican National Convention.

Face covering prohibitions took hold in Canada when legislators in Québec passed an emergency anti-protest act. After unprecedented student strikes, the Montreal city council 'quietly passed a bylaw banning masks during protests.'

Some wondered whether mandates against what people cannot wear on their face creep to other U.S. cities. In light of the newly proposed Oakland ordinance against 'shields,' one could assume so, since facemasks can serve as coverage for both surveillance attempts and harmful chemicals released by the police.

? ? ?

Roland Barthes’ The Fashion System was the first I came across which argued that fashion is an abstracted notion, making it particularly pliable to financial schemes. He argued that luxury fashion speaks of work and leisure in the same manner:

In Fashion, all work is empty, all pleasure is dynamic, voluntary, and, we could almost say, laborious; by exercising her right to Fashion, even through fantasies of the most improbable luxury, the woman always seems to be doing something.

Few would disagree about the semiotics of the fashion magazine as Barthes laid them out, and his observations spell out even more trouble since sales of luxury goods are said to rise exponentially during recession epochs. Handmade, carefully crafted garments, in contrast to mass-produced 'fast fashion' that relies primarily on exploitable labor in the global South and North, appear ever more precious and scarce as Fashion (capital F, as Barthes uses it) hoards profits and enriches itself in a fast-decaying market system.

In that light, Fashion and Occupy seem to stand in opposition, if they face each other at all. Occupy was formed as a response to the commercialization of virtually every aspect of ordinary life, and the fashion industry is often (and rightfully) singled out for its callous collusion with Wall Street.

Yet it is crucial to look beyond the dominant influence of the industry into places it does not or cannot pervade entirely. How should one consider the actuality of material life in the presence of—but also beyond—the financialization of everything? The notes above are meant to act as a generative springboard for further discussion on this question.